AS THE YOUNG CREATOR OF GRAPHIC NOVELS, ZIMBABWEAN ARTIST BILL MASUKU IS BREAKING RULES AND BARRIERS. WITH LITTLE ELSE BUT HARD WORK AND A SUPPORTIVE MOTHER, HE NOW HAS PRODUCTIONS GOING WITH NETFLIX AND DISNEY.

AS A YOUNG BOY FROM HARARE, THE BUSTLING capital of Zimbabwe, Bill Masuku always loved to draw. which his teachers accepted as part of his identity.

Home, however, was a different story. His father would tear up his drawings.

“I lost some really good ideas. In the end, I learned to draw really fast,” says Masuku in an interview with FORBES AFRICA. His ability to draw came in handy a decade later, when he had to do storyboarding, an art that requires a skeleton of an idea and quick turnaround.

Masuku still drew in high school but began focusing on his textbooks in order to get into university. At Rhodes University in Makhanda in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa, he studied for a bachelor’s degree in commerce, majoring in Management and Information Systems. In his first year, he took on six subjects, as opposed to the usual four.

After cracking a joke in one of his classes, a classmate suggested he checkout NatCaf, a comedy troupe popular at the university.

He did, and got in.

Little did Masuku know that this would be the start of a career in the creative industry. He began performing for NatCaf regularly, and was getting recognized.

“They don’t know Bill, they know the performer. There is a separation between those two things. And around this time, I was getting my confidence back. And so I started drawing more and more. I think I’d gotten into the habit of just not drawing as much because it had been instilled in me that if I draw, these things will be destroyed, burned, torn up, or thrown in my face. I got my confidence back after doing performance comedy,” says Masuku.

Critical to this development was when Masuku started dating too, as relationships introduced him to feminism, intersectionality and Frantz Fanon. It made him look at justice with fresh eyes.

“Maybe just a black man in spandex does not work. And I thought, ‘let me rework this idea’. But I also had my whole university career, so I needed to rework it very slowly and be very intentional about my writing, because it was much deeper than just punishing criminals. In that time, I realized crime is a symptom of bigger structural problems.”

Shortly after that, Masuku left university after being in hospital for a month, struggling with mental health. He went home to Zimbabwe.

“I don’t have a degree to my name, I don’t have money to my name. All I have are these ideas that feel like ripples.”

The more he sat on them, the more the ideas started speaking to him; he knew he had to jot them down as quickly as possible. He hadn’t felt like that since he was a kid.

The lack of access to proper digital infrastructure on his return to Zimbabwe could have deterred him, but he did not allow it to. Creating more opportunities for artists like himself in his country, he kept the art alive and contacted other talent in the local market.

Finally, in 2016, Enigma Comix Africa was born.

“Enigma Comix had a bumpy start looking for partners and investors in Zimbabwe. I was totally unknown, added to the fact that my art wasn’t at the community standard. Eventually, it became a branch off my brother’s company in South Africa.”

Masuku says the biggest challenge in creating his company was and still is distribution. With only a handful of comic book stores in southern Africa, it has been difficult to create a sustainable supply chain outside of the convention circuit. He adds that the advent of digital comics and websites that host creators has been a massive boon for getting content into new hands, “though the stats show that the largest consumers digitally are in the US and parts of Europe”.

“One of the biggest rewards I believe is that my Enigma Comix Africa books serve as a portfolio and proof of concept to open dialogues about access, literacy, and creative ownership in Africa.”

Unfortunately, the local Comic Con Africa offices said his art was not “good enough and to stick with writing”. It was the first devastating blow to his ego. He took the taxi home, trying not to internalize the rejection. The very same day, despite the negative feedback, he started sketching the first cover for Razor-Man – one of the best things he’d drawn at the time.

So on after drawing the cover, he was invited to a local Comic Con. He didn’t have merchandise, posters or a full comic to sell, but he wanted to do it. He asked his mother for help. She gave him $100.

“That was the sum total of my investment [for] diving into my art career. It was a lot of money. For me, it was the most money I had thrown at something I was passionate about.”

Unfortunately, $100 was not enough, but he made a plan to cut corners, like reducing the number of comics to print, in order to be at the event.

From that event, Masuku knew graphic novels would take years of persistence and consistency. Superman didn’t become popular overnight. He took a day job in 2017 to get consistent income.

“You leave the house in the morning, you get home in the evening, and you’re exhausted. There’s no way. You just get home, shower, eat, sleep, wake up the next day. There’s no time to be creative. And you can be creative, but you’re hungry. You can’t be creative, there are no lights on. There’s a lot of those small socio-economic factors that you don’t consider when you’re not producing.”

Masuku got back into comics full-time in 2018. He made Captain South Africa a woman. There was a lot of pushback and debate, to the point that he took the new posters off his table at an event.

“Surely, there must be more than black male superheroes, you know. I want to see progress now, like America took so long to get to where it is comic-wise. We can circumvent, we can skip all those steps. We are diversifying. People did not want to hear that at all.”

At the same time, his uncle was keeping an eye on his work, and gave him a digital drawing pad. Masuku had to make the decision between digital and traditional drawing in time for the FanCon Comic Con Cape Town event in 2018. His drawing pen wouldn’t stabilize. He says looking back at that work is like looking at a “cursed grimoire”, but it reminds him how far he has come.

He describes the first big Comic Con event in Cape Town as a “mist” of people, surprised by how many geeks there were, but the second event he went to was a “fog” of people, dense and overwhelming.

At the first event, he did live drawing, where people attentively watched him.

Masuku knew that he wasn’t the first African comic creator, but that moment reminded him that he was breaking barriers.

Parents would come to his table, not necessarily to buy, but to show their children how he was drawing and ask his advice. And Masuku gave the advice he would have wanted when he was a child.

He was invited to Comic Con Africa as a guest in 2019. Seated next to international titans of industry from Marvel and DC, he tried not to let imposter syndrome overcome him.

Then, the pandemic hit. Masuku says for freelancers who work from home, the world got smaller.

He ended up going to more events online. He began getting more business.

“I’m so used to self-managing, so used to a high self-discipline. If I don’t work, that’s a wrap. I don’t have a manager standing over me, checking my work, I have to be my own quality control. I have to be my mailman. I have to be my secretary. I have to be a jack of all trades,” he explains. “And that jack of all trades, because I was making my own comics for a long time, meant that I could slide into wherever you want. Want me to write something, draw something? That’s cool. You want my advice on marketing? Here you go.”

Masuku received an opportunity with the British Council to create a story about the circular economy. Though it was amazing to receive bigger jobs, the pressure on him to deliver increased, especially when faced with infrastructure problems such as Zimbabwe’s notorious power cuts.

One of the power cuts fried his laptop and drawing tablet cable.

Kugali Media, a visual story-telling brand using comics, graphic novels, augmented reality (AR) and animation in, contacted him asking him to work full-time at the end of 2020. This was another big break for Masuku. One of the projects he worked on was Nani, a fantasy graphic novel inspired by African mythology, which raised $58,235 with KickStarter to fund the project. Kugali Media has worked with big names like Disney, specifically on Iwaju, an animated original series.

“I was still young, and am still young now. But I was at the grassroots of this journey. Now, there are sapling trees. I’m getting to the point where I’m going to bear fruits, but people are starting to look at the flowers blooming.”

At Kugali, he got to shape comics as they happened. Being “a jack of all trades” paid off in the end, because they asked him to become an assistant editor.

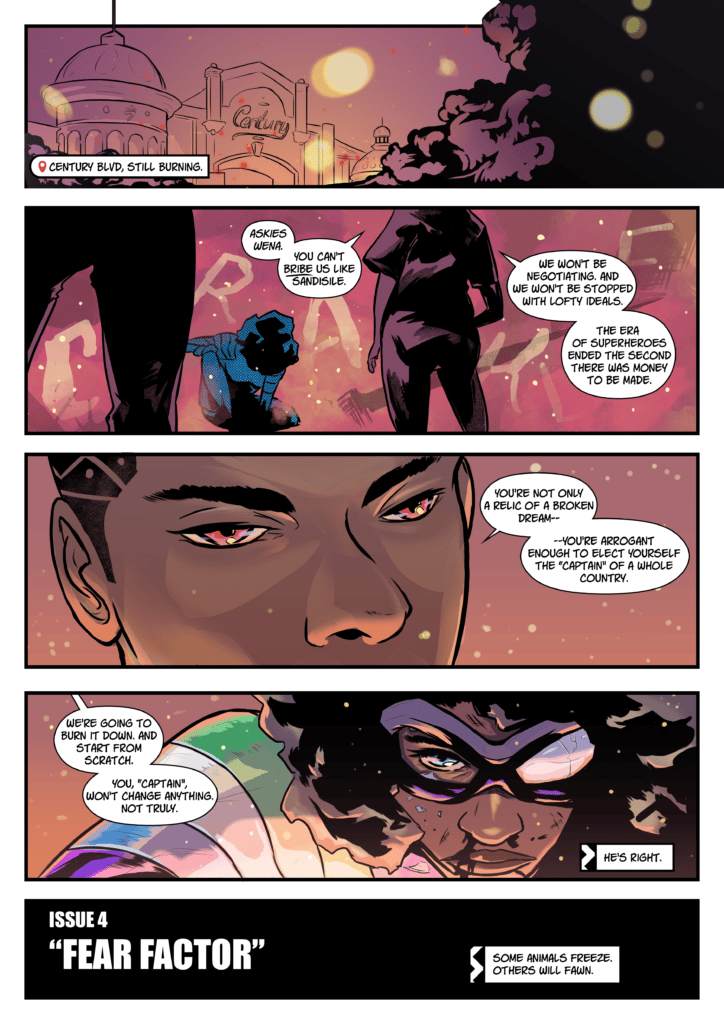

The Nommo Award-nominated comic artist’s books include Razor-Man, Captain South Africa, Nani and Kokou. He has contributed to anthologies such as Kugali Anthology Vol 1,Comexposed’s Comic Up Vol 1, A Womb with a Heart That Beats All Over The World (Poetry), Sublime: $5 at the Door, and After the Fall: A Post- Apocalyptic Anthology.

“Whether it’s a local studio or international studio, people are starting to take notice of Africa as a creative resource. People have told stories about Japan, the Japanese tell really good Japanese stories. The Koreans are taking over with their K-pop, dramas, and even web comics,” he explains.

“But Africa is still this big myth. And for a company to say, ‘okay, here’s this country, let’s tell its history or its culture or its mysticism, very specifically not blending into anything else’, that is this huge opportunity. That’s one that has been waiting to happen. Let’s put the creativity in African hands if you want to tell an African story. Let Africans tell that story.”

At the end of 2021, Masuku discovered that Netflix was sponsoring story artists. Through power-cuts and the demands of a full-time job, he applied. He realized after the deadline that he hadn’t attached a file – through either power-cuts or refreshing a page. He panicked, but they still accepted his application in the end.

He went through an intensive storyboarding workshop with Triggerfish Animation in two parts. Masuku ended up getting the job with Netflix, and is still in production.

This year, he’s going to Comic Con Africa as a guest, and working on a new graphic novel with Kugali Media. In April, he lectured at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa on the topic of Afromanga.Masuku is only 29. With his brand of African stories, this may only be the beginning, for him and the continent.