Even though the world has begun to open up, the after-effects of the pandemic on the supply chain are noticeable. Limited shipping containers and flights have created a backlog putting massive pressure on component manufacturers. Where does that leave Africa?

By Tiana Cline

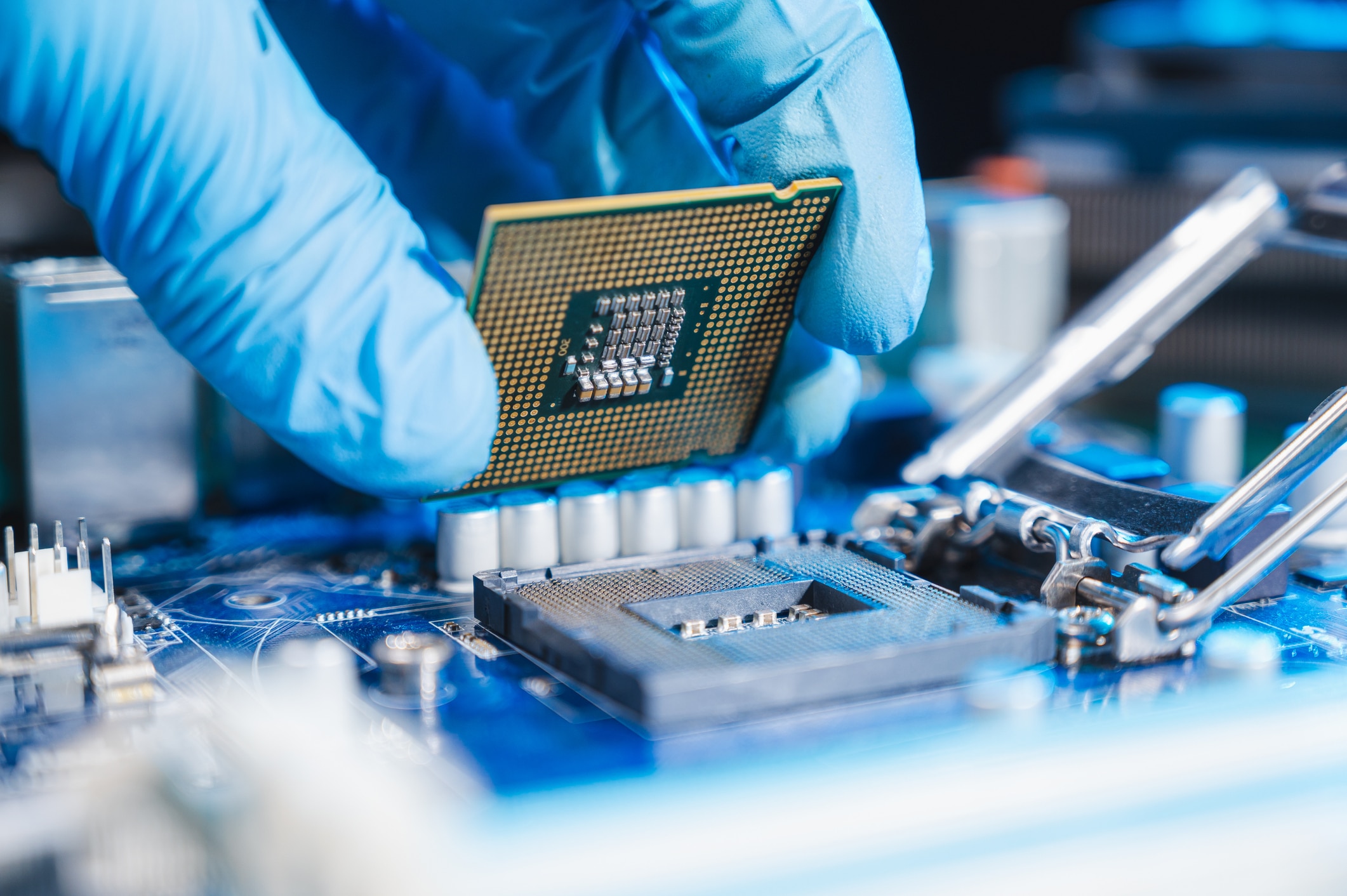

EMICONDUCTORS POWER the modern world. They’re not only in every single device that we use on a daily basis, they’re a key part of data centers, factories, cars, household appliances, gaming consoles and aircraft. But now, there are simply not enough to go around. As the demand for electronic devices grows, the global chip shortage continues to impact a number of industries and what Africa is now experiencing is less product, significant price hikes and a slower supply chain as big brands prioritize high profits over stocking up the emerging world.

“Because of the chip shortage, logistics has really become a real challenge for us.

The North African markets are really suffering when it comes to stock allocations. Distributors would rather service bigger markets where logistics are easier,” says Johannes Groenewald, the head of Demand Factory at the Tarsus Technology Group, an IT reseller with offices throughout southern Africa. Another issue is that 70% of the technology reseller market in Africa is made up of government spend but when the pandemic hit, IT investments were cancelled in order to focus on Covid-19 programs.

“Botswana was our biggest market by quite a margin but for the past two years, they’ve invested nothing in IT purchases,” adds Groenewald. “This puts the market back a couple of years because in Botswana, for example, students get subsidies to buy hardware for their studies. Because the budget has been reallocated, the technology becomes outdated and there is now no availability to supply that market.”

Instead of supplying entry-level devices at a lower margin, many manufacturers are chasing volume, choosing to serve more profitable markets with products and services where the risk of losing business is much higher.

“If you compare selling a professional device in a country like Zimbabwe compared to the US, it’s much more than margin reach, it’s the surrounding peripherals, the docking station, the support. In Zimbabwe, it’s just a naked device and very few units are sold in these markets,” says Groenewald.

“The backlog has to be caught up first,” adds Mark Broude, Kemtek Imaging Systems’ CEO and COO. “The demand will continue to outstrip the ability to produce product chipsets and I believe it will take between five and seven years to get production to full capacity.”

While the instability in Eastern Europe may not directly impact Africa’s component supply, there are fears that it could intensify tensions between Taiwan and China. “Some components are exclusively manufactured in Taiwan so any conflict would have a huge implication on local availability,” adds Groenewald. Taiwan and Samsung Electronics in South Korea currently dominate the automotive chip market.

While new chip factories are currently being built, they will only become operational in 2023.

“There aren’t many manufacturers which have the financial ability to fund a new plant,” explains Paul Lee, Deloitte’s global head of research for the technology, media and telecommunications industry. “Intel is investing $20 billion on a new semiconductor plant but there aren’t many entities who can do that. It often has to be a combination of government subsidies and manufacturer investments.”

Even though the world has begun to open up, the aftereffects of the pandemic on the supply chain are noticeable. Limited shipping containers and flights have created a backlog that is putting massive pressure on component manufacturers.

“If anything, our expectations on shortages have exacerbated. We are less optimistic about supply increasing to meet with demand,” says Lee. “The pandemic has been very confusing because it’s been a lot longer and it has manifested in different ways than what most people expected.” Semiconductor chips are also not the only

component in short supply. Even though there are many companies that supply LCD screens, there are only a few manufacturers. With the medical industry so invested in going paperless, an increased need for touch devices meant other hardware – like scanners, printers and low-end phones – couldn’t be produced.

“The market is dry from factories being closed during lockdowns and shortages in raw material. There was a huge backlog in supplying LCD screens to developing world markets which is only now normalizing,” explains Groenewald. “A lot of devices earmarked for normal market consumption ended up in the medical industry.” Manufacturers also have to consider other minerals which go into semiconductors such as lithium and copper.

“There are the rare earths which are required for mobile phones. Historically, it wasn’t viable to extract these elements from end-of-life devices but now because mining those minerals is challenging, smartphones are being designed to be recyclable,” says Lee. “It’s not just about how you assemble it, but also how you disassemble it so that you can reuse components within that.”

Despite supply chain issues, Deloitte predicts that the semiconductor industry will earn over $600 billion globally in 2022. Microchips may only be produced by a handful of manufacturers today, but they’re essential to almost every industry and the absence of just one could result in a device not getting made or sold.

“The long-term demand for semiconductors doesn’t go away. The long-term demand for devices doesn’t go away,” says Lee, “but the shape of the increase in that demand is going to be anomalous until, perhaps, 2024.”