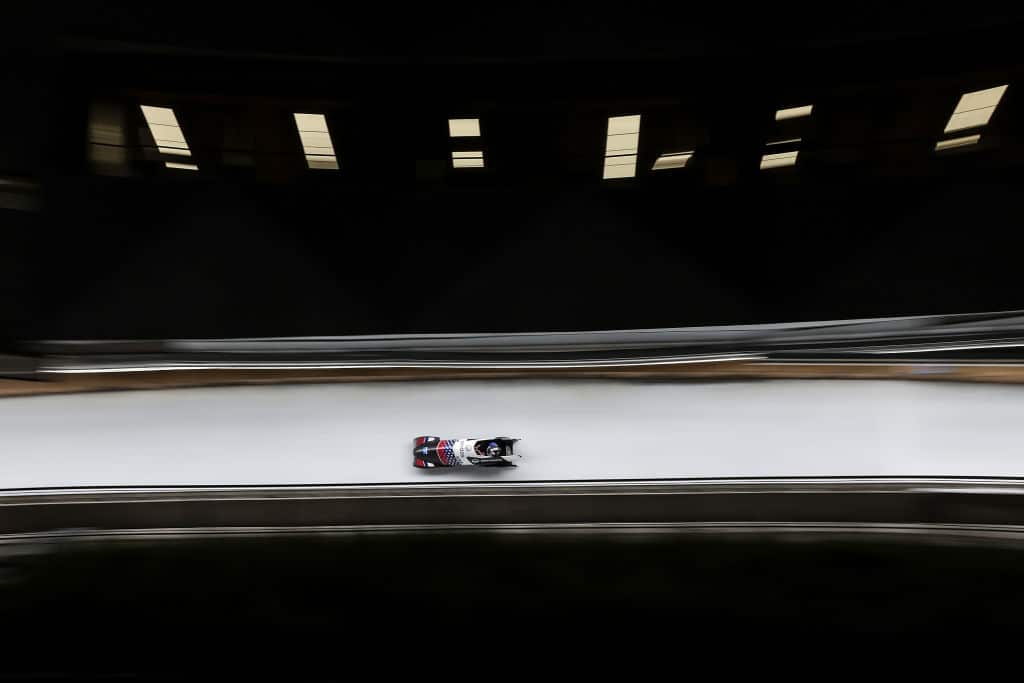

Next to Winter Olympic equipment like ice skates and ski poles, bobsleds look like tanks—giant hunks of metal and fiberglass that, in the four-man event, measure 12 feet long and can weigh over 500 pounds. But while they can withstand a knock against a wall while screaming by at 80 miles an hour, they’re not as invincible as they might seem.

Morgan Tracey, director of operations and compliance for the U.S. Bobsled and Skeleton Federation, knows that well. A couple of years ago, she recalls, one of the bars the bobsledders grip during their running starts snapped off a sled. “We had to order basically a piece of metal and make it, and it went all over Europe,” Tracey says, adding, “You can’t go to a bobsled store and get a bobsled part.”

With equipment that is so clunky yet so delicate, it’s never easy getting a bobsled from Point A to Point B, and this year, the process was even harder. As Team USA’s sleds hurtle down a roughly mile-long ice track over the next two weeks in the mountains outside Beijing, whipping around 16 banked curves in a minute or less, it will be just the final stretch of a global journey that required similarly precise coordination.

Bobsleds aren’t the only sleds being used at the Beijing Olympics. There are also two types of flat sleds, used in skeleton (in which individual athletes travel face-down and head-first) and in luge (featuring one or two riders face-up and feet-first). But those sleds are just 75 pounds or so on the high end, so athletes can bring them on commercial airplanes, keeping the equipment safe inside custom-cut boxes of heavy-duty styrofoam. Bobsleds, on the other hand, weigh no less than 359 pounds and have to be loaded by forklift off a truck and onto a cargo aircraft or boat.

Twelve bobsledders are slated to race for Team USA at the Beijing Games, across four events: four-man, two-man, two-woman and monobob, a new event on the women’s side that features a solo rider in a seven-and-a-half-foot sled. They’ll compete in eight sleds, each of which was loaded into a 4x4x13-foot crate and surrounded by other equipment the team will need: backup shoes, helmets and speed suits, but also spare parts, special wrenches and weightlifting equipment, including squat racks and medicine balls. The team has to track down specific flat-bed trucks that can accommodate those enormous crates.

The process was made more complicated by the current international shipping crisis. Few shippers were available, and prices were “astronomical” and “insane,” says Tracey, who oversees logistics for Team USA’s bobsled and skeleton athletes. (Luge has its own federation.)

This season, the American team had to pay 11,200 euros ($12,700 at Friday’s exchange rate) per crate to fly its sleds from the U.S. to Europe, up from $4,122 per crate the previous season, according to the federation’s chief financial officer, Lisa Carlock. The team was then quoted roughly $9,900 per crate for the flight from Europe to China but is still awaiting the final bill—which could be even higher.

To save money, the team is considering shipping the sleds back to the U.S. on a two- or three-month voyage by boat. But that was not an option getting to Beijing: The international racing schedule ended just three weeks ago in St. Moritz, Switzerland.

All the sleds had to be trucked up to Frankfurt, Germany, before heading to China. With limited options to choose from for the flight, the federation used a shipper who transports horses for equestrian events and orchestra equipment, in addition to bobsleds. The crates were loaded on January 18 and picked up on January 20, but they didn’t clear customs in China until a week later.

It was another couple of days before they made it to the venue in Yanqing, northwest of Beijing, but that timetable still qualifies as a success. The federation dealt with travel cancellations this season, including one that, combined with a weather-related delay, made bobsled pilot Frank Del Duca almost a week late to an event in Park City, Utah. Had the international federation not stepped in and moved some races around, that setback might have kept him from qualifying for these Olympics.

There’s reason to worry even when the sleds are in transit. Although the sleds used in both bobsled and skeleton have steel frames, the metal can bend. Bobsleds are generally pretty stable in their crates, but accidents happen. “A skeleton sled can go up to 90 miles per hour and take hits at six G’s, but it’s interesting what a couple drops through TSA or baggage claim can do to it,” says Tracey, a former skeleton racer herself who is at her first Olympics in an official capacity with the federation.

The transportation drama is heightened by another reality: The team doesn’t bring any extra sleds, partly to keep costs down and partly because athletes want to compete in the same equipment they’ve been training in. It’s up to Marc Van Den Berg, the federation’s sled technician and one of 14 members of the U.S. Olympic bobsled and skeleton delegation beyond the athletes, to deal with any damage. Luckily, while the runners—the metal blades under the sled that touch the ice—sometimes get damaged and need to be replaced, the sleds themselves can last for years with proper maintenance.

Of course, Covid-19 adds yet another impediment. Multiple members of the bobsled and skeleton delegation reportedly tested positive for the virus in the lead-up to the Games, an outbreak that kept bobsledder Elana Meyers Taylor from serving as the U.S.’s flag-bearer at Friday’s Olympic opening ceremony. On the bright side, the bobsled events are not scheduled to begin until February 13, so there’s still time for the athletes to recover.