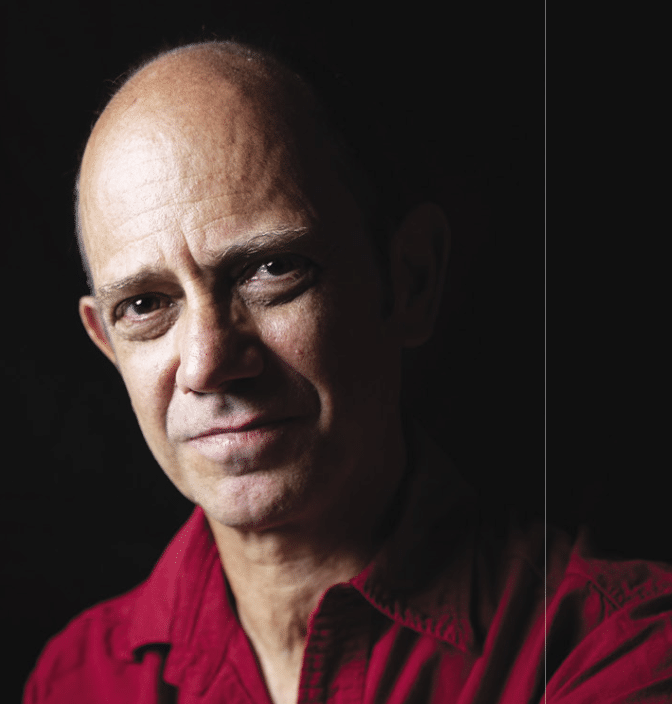

In an exclusive interview with FORBES AFRICA, Damon Galgut, last year’s Booker Prize winning South African novelist, dwells on the fluid, filmic dynamism and shifting narrative perspectives of The Promise.

BY ALASTAIR HAGGER

“THUS IN DREAMS DO THE DEAD return to you,” writes South African author Damon Galgut of Rachel Swart, the spectral focus of his 2021 Booker Prize winning novel The Promise. Spanning four decades in the life of a white Pretorian family, the novel traces the characters’ fragile moral commitment to a promise made by the dying Rachel to the household’s domestic worker, Salome, that she will be given ownership of the little house on the family’s farm where she resides. At four funerals, spaced roughly a decade apart across the narrative, the family reunites in grief, but always with the deeper wound of Salome’s betrayal – and Rachel’s restless soul – calling quietly but insistently for their attention.

“The jumps in time were exciting to me, because they allowed me to explore what happens to individual people as time moves on,” Galgut says, via Zoom from his home in Cape Town. “The four decades of South African life it covers are also the four decades of my adult life – the years I’ve spent sort of consciously thinking about dwelling in South Africa’s ever-changing new realities.”

Author of nine novels (he was also shortlisted for the Booker in 2003 and 2010), Galgut was born in Pretoria in 1963 into a Jewish family; his mother (“always a bit of a spiritual seeker”) converted to Judaism after meeting his father. In The Promise, Rachel reverts to her Jewish faith before her death; he describes the character’s ghost as “almost visible at certain moments, when the light or the mood is right, but only to those who are ready to see”.

“If I’m writing about these other aspects of existence, why not assume that some sort of afterlife is one of those?” Galgut says. “And allow Rachel – who would otherwise not be a presence at all in the book – a brief moment on stage?”

The universe drops away into a dizzying abyss in every direction… And seen on that scale, we are one absolutely minute speck in this endless, infinite range of views.

These shifting narrative perspectives are the thrilling stylistic heartbeat of The Promise – the characters’ internal monologues bleed together like a shared but ruptured consciousness, with the reader feeling continuously reawakened from one mind’s dream into the next.

“What I felt, when I first started working on this novel, was frustration with the self-imposed limitations on the third person voice,” says Galgut, who brings to his process the more dynamic narrative experiences of theater (he has written four plays) and screenwriting. “What you can’t do is go into the minds of various subsidiary characters that might be present, or to look up close at a particular detail, which might actually tilt your perception of the scene – you’re meant to maintain a kind of a steady viewpoint which removes the narrator from being a presence.”

Instead, The Promise adopts a fluid, filmic dynamism, whereby the narrative landscape is traversed without obstacles, as if the reader was piloting a drone: our attention is threaded through place and time in a dizzying stream of human thought (in one remarkable sequence, we even run for a while in the minds of jackals).

“This temptation to become untethered from the scene and the central characters is always there,” Galgut says. “It’s always interesting to look at, you know, the person who’s watching the body, or somebody who is at the edge of the scene. And if you are going to push the frontiers of the realistic world back as far as you can, you need to include some other unexpected consciousnesses.”

His interest in other realities is not seeded by religion, which he says “diminishes the mystery of the universe”.

He admits instead to a fascination with the bleak infinity of the unknown, and the exhilarating limitlessness of scientific wonder. “The universe drops away into a dizzying abyss in every direction,” he says. “And seen on that scale, we are one absolutely minute speck in this endless, infinite range of views. The true mysteries of the universe are absolutely, ball-looseningly terrifying.”

Is he grounded by a sense of home, or of hope for a South Africa whose flaws are so chillingly dissected in the novel? Or does his homeland struggle with the empathy that The Promise suggests is still possible through a long but determined excavation of personal and national trauma?

“It doesn’t give me any pleasure to say that I think South Africa is at the lowest point, at least morally speaking, that I can recall,” he says.

“There was a real sense in the 90s that we could put the country on a different sort of footing and make a different kind of future for ourselves. Even white South Africa, in all its recalcitrance, felt at that time potentially more generous and open to solutions than maybe ever before. We are a long way from that now, and I’m really unhappy to say that it’s precisely because of what the ANC has done in power that the goodwill I’m talking about has mostly evaporated.”

Home, in The Promise, is “a blizzard of things at war”. The dilemma created by the broken covenant at the novel’s center – that Salome must be given the home she has been promised – is thus a distillation of the suspicion and distrust seeping through the foundations of South African life.

“I don’t think that notion of hope, that feeling of sanctuary or belonging, is really possible in a place like South Africa. The very notion of the ground you’re standing on is contested between different parties,” Galgut says. “So on the one hand, my sense of home is my apartment, which feels like a kind of a small sanctuary for me. In a larger sense – I don’t know that South Africa can offer that sense of refuge.”