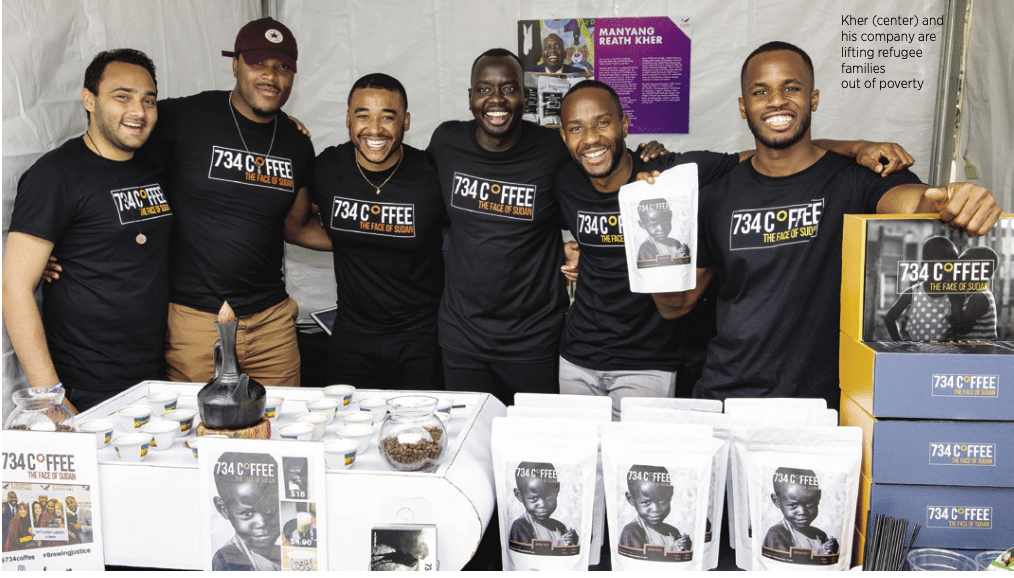

The rewarding story of a South Sudanese coffee entrepreneur who spent his childhood as a refugee braving bullets and snake bites. His company, 734 Coffee, is named after the geographical coordinates of the camp where he was raised. Uprooted by civil war, Manyang Reath Kher was invisible there, not anymore.

BY RIDHIMA SHUKLA

IN AKOBO VILLAGE IN THE HISTORIC Gambella region, the sun shone bright, the forest was green and the children laughed with gay abandon. The men reared cattle and the women tended to their kitchen gardens. The ponds had plenty of fish and the people were content. But their simple lives were about to be thrown into utter chaos.

The late 1980s saw the start of the brutal civil war in Sudan that burned villages and plunged the region into abject poverty. In the middle of this bloody carnage was Manyang Reath Kher, the three-year-old son of a cattle farmer who now recalls the chilling horrors of the conflict as we chat to him via Zoom. Today, he is a coffee entrepreneur educated in the United States (US) and on a mission to change lives in Africa.

Back then, he lived in Akobo, a village of no more than 300 people in South Sudan, with his parents and infant sister.

As the conflict surged, like many others, Kher’s father joined the resistance movement. His tiny village served as a stronghold for the rebels for over a year, providing them with relative safety and keeping them fed and alive.

But life for the families here was about to take a turn for the worse. As little Kher skipped in the forest and played with fish in the ponds, the military had seized power in the capital and the consequences of this political shift in the African nation drew closer home.

As one of the last remaining strongholds of the resistance movement, Kher’s village became a military target. The residents disappeared into the forest with whatever they could carry on their backs. A baby strapped to her chest and a toddler by her side, Kher’s mother, Dimma, along with other women and children, made her way into the depths of the forests, while the men held fort on the frontlines.

After restless days roaming in the forest, Dimma decided to part with her son hoping to give him a shot at life, which she wasn’t sure she had. Her brother, Nyayual, carried Kher to the Ethiopian border, but just before that, the fleeing families were chased by bullets as they ran for their lives to cross the river.

Kher’s uncle was shot in the back.

He somehow managed to cross the river and hand over his nephew to a group of children before falling to the ground and breathing his last.

Kher roamed freely in the woods, playing hide and seek with the shadows of tall trees and tickled by the

fish swarming the lakes. “I do not remember

many details; most of my young life was spent in a refugee camp,” says Kher.

In the summer of 1991, Kher and several other children were declared refugees and settled in a camp at the Sudan-Ethiopia border.

“I was lucky to have found people from my village and children who were kind to me.”

Inducted into a home for children, Kher lived on ration cards handed out by UNHCR workers, which afforded him a meal a day. Basic education in Maths, English and Science was also provided at the camp.

In this fractured new world, most days were the same; people were hungry, distraught and traumatized.

“I remember people dying everywhere even from mosquito bites,” says Kher.

Shortly after one of his friends succumbed to cholera, Kher was bitten by a venomous snake.

The severe pain had him bedridden and enduring fever for six months, but he survived this ordeal too and recovered to carry on as a young refugee not knowing how life would pan out.

“At the camp, rains would bring disease and discomfort but we would all tell each other that it can only rain so much.”

Wise words that stuck with him and led him to not only find a life outside of the encampment but also build one helping other refugees.

“As children, we could not wait to be men. Growing up was a boon, we desired to be on our own.”

In the early 1990s, the conflict in Sudan garnered the attention of Christian groups in the US who empathized with the cause of the South Sudanese. By the end of the decade, the cause had been championed for years and found a prominent place in US Congress.

American president George W Bush also made it his policy priority, which saw the signing of a peace deal (during his second tenure) between the rebels and government, enforcing a permanent ceasefire.

Despite spending his entire childhood in a refugee camp, 13 long years to be exact, away from his parents and unaware of their wellbeing, Kher calls himself “lucky”.

“I was lucky that the Catholics charity found out about the snake bite and was very empathetic. They checked on me for years and made arrangements for my higher education.”

In 2005, he left for university in Richmond, Virginia, in the US. Initially interested in Human Rights Law, he changed his mind and pursued International Business instead.

He understood the value of money early on.

He believed that to really help people, he first needed to be able to finance it.

“I was always going to study business. I was always motivated to do something for the people.”

His journey towards entrepreneurship began at his university campus, where he raised money selling produce from a community garden.

As a refugee who grew up in the coffee-rich lands of Ethiopia, Kher was close to the bounties of nature. But it wasn’t until he noticed the craze for coffee in the US that he even imagined trading in the commodity.

“At university, my friends were drinking coffee all the time and paying good money for it too. I wanted to tell my story through my work and I thought coffee could help me do that.”

In 2010, he registered a coffee import company in Richmond and named it 734 Coffee, after the geographical coordinates of the refugee camp where he was raised.

After all, the coffee was Ethiopian and the company intended to employ other refugees who had lost years of their lives to the conflict in Sudan.

“The fear of disappearing was overwhelming, the pain wasn’t! I wanted to tell our stories; I wanted the world to know.”

Along with learning the inner workings of running an international import/export business, the logistics, and building a network of buyers.

Kher was slowly rebuilding his life. He was also actively working with refugees to help them rehabilitate and restart their lives after being uprooted from their native land.

“I wanted my people to know I had not abandoned them. After all they were the family I grew up with.”

He started small but his efforts helped several families in the Gambella region of Ethiopia to earn an income and survive poverty and hunger. Along with a friend from the refugee camp, he distributed fishing nets to over 100 families giving them a vocation in hand.

He followed the problems faced by displaced populations in Africa and that landed him in a classroom to share his ideas and experiences with the students of the Human Rights curriculum at George Mason University in the US in 2017; a role he still continues.

The road to entrepreneurship was slow and bumpy; it took him six years to acquire the license for importing coffee beans from Africa to the US. But it was worth the wait.

After much trial and error and years of networking, his business gainedground. TheCovid-19pandemicdidn’thelp,buthepivotedto online sales. In 2019, 734 Coffee had 300 former refugees working as employees at the cooperative farms in the Gambella region of Ethiopia.

“We want to improve lives while improving our business,” he says of his simple business philosophy.

Kher is currently setting up a water cleaning and packaging unit

in South Sudan. He believes his plant will not only offer employment to the local populace but also provide them with inexpensive drinking water in reusable packaging.

The facility aims to employ over a 100 people over the next few years with a focus on those whose lives have been disruptedbyconflict. “Wehavetoredefinethemeaningof human rights, we need to understand what we are fighting for. The reason it took me 13 years to leave the encampment was because there were many disruptions,” he says.

After more than two decades apart, Kher finally met his mother and sister in 2012.

He also found out about his father’s demise during the war.

Up to two million lives have reportedly been lost to the civil war in Sudan, since the1980s. Hundreds of thousands have been internally displaced. Despite the peace deal and bifurcation of Africa’s once largest nation, reports of human rights abuse and conflict continue. People like Kher’s family are still fleeing their homes to save themselves from famine, abuse and starvation, only to find years lost in a refugee camp.

Today, South Sudanese make up the largest refugee population in Ethiopia’s refugee encampments. Yet, Kher remainsoptimistic:“Lotsofproblemswerebroughtto [Africa] but, today 70% of our decisions are in our own hands and that is how we can and will change Africa.”

Today, he hopes to fund the higher education of hundreds of refugee children and give them the opportunities he was blessed with. Indeed, as he believes, “the rains do stop”.