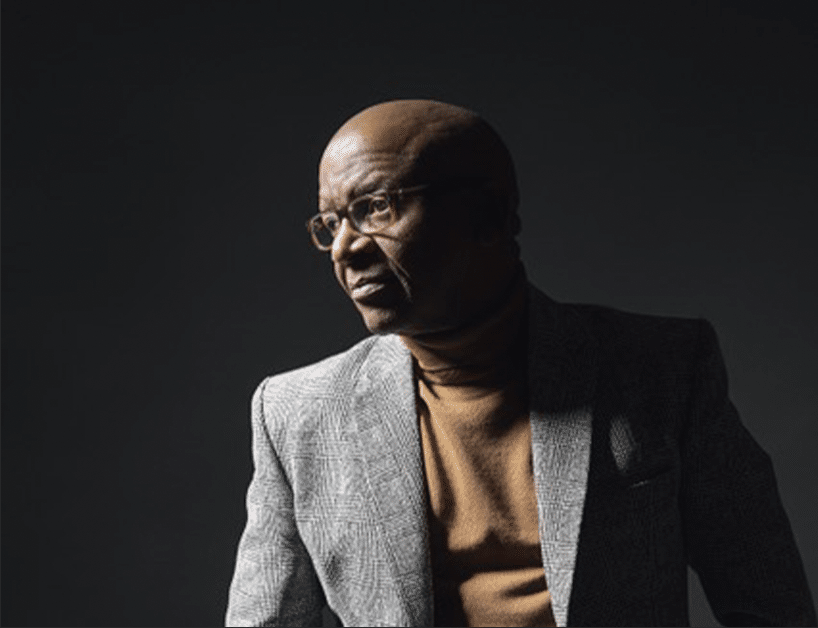

With two-lifetime achievement awards under his belt this year, Grammy award-winning South African musician and The Lion King composer Lebo M speaks to FORBES AFRICA from Los Angeles on what actually set the tone of his musical journey.

“As a young man, you would think I would be nervous or apprehensive. But I’m glad I was not. I was hungry. I was ready. I was doing an assignment that came by default. I was just looking forward to getting paid, honestly.”

It’s 1AM in Los Angeles and Lebo M is in front of his laptop speaking to FORBES AFRICA with an upfront confession: “Just bear with me, I am not very good at interviews.”

For a man who has enthralled thousands on stage for live performances for over 40 years, this is an unlikely opening.

And the 57-year-old Lebohang ‘Lebo M’ Morake reaches out for the ocne thing that will kick-start this interview – much as it did his career.

He carries his laptop to the kitchen counter and makes himself a hot cup of coffee.

Whilst we shall soon dwell on the association between coffee and this connoisseur of music, Morake starts by talking about his life in Los Angeles, where he is now located for work reasons. After many months in lockdown in South Africa, this has been a welcome change.

“The journey of Simba who grows up in exile is the journey of Lebo M who grows up in exile. I didn’t grow up to become a king like Mufasa but my biggest project is The Lion King, whose storyline became very personal to me.”

“Don’t get me wrong,” he says. “I like being here in Los Angeles. I haven’t left home [in South Africa] since Covid (lockdown), so I am getting my groove back. From all the lack of traveling, my body went into shock. For over 25 years, I used to go from one place to another every two-three months. And I’ve been on shutdown.”

Currently, Morake is working on two international movie projects awaiting release in November, and he can’t divulge more details yet.

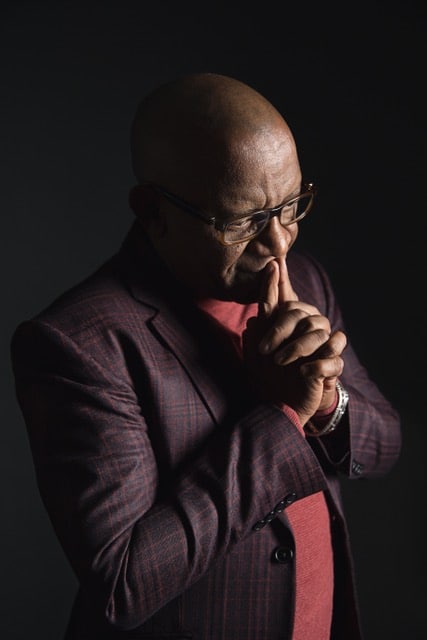

There is another reason he has been in the news. Recently, he was recognized with two Lifetime Achievement Awards.

“My first Lifetime Achievement Award was absolutely amazing. It was an experience with Mzansi Magic. But the South African Music Awards’ Lifetime Award became very personal and very special. Because basically, I don’t want to use the word ‘validates’, but it says my peers acknowledge me specifically in the music business – holistically and all. I cried a few tears for this one,” he says.

You would think ‘a lifetime’ of working would slow Morake down. It’s quite the opposite actually. Besides the films in Los Angeles, his new reality show Coming Home recently released on Mzansi Magic and Showmax.

We ask the musical legend: “To what do you owe your success?”

Morake laughs stirring his hot beverage. “Wait, that’s the first question and it’s so difficult. I haven’t even had my first sip of coffee. I thought you were going to go easy on me.”

He takes a deep breath, sips his coffee and despite the poor quality of the Zoom video call, you can see him almost smirking as he thinks of what to say next.

“For me, being South African, my ‘South African-ness’ is the epitome of the essence of who I am as an artist,” he says, “I am so passionate about who I am and where I come from.”

Born in Tladi, in one of Gauteng’s biggest townships, Soweto, Morake’s journey into music began almost 43 years ago when he left school with no formal musical training and began working at The Pelican.

According to MusicInAfrica, The Pelican nightclub is an “icon in Soweto’s vast cultural and musical history”. It also forms part of Soweto’s political history which has seen talents such as Ladysmith Black Mambazo and Abdullah Ibrahim perform on The Pelican stage.

“My first ‘quote unquote’ job as a professional at age 14 was at a highly-advanced institution or nightclub called The Pelican which was the best in the country, showcasing their best talent,” Morake recalls.

“I consider myself to be a part of the transition generation because even from a young age, I was exposed to the industry.”

Morake recalls how magical the music scene was “back then”. It was not uncommon that a large number of musicians could not read or write music but were self-taught.

“When we emulated American music, whether jazz or RnB, there was always the age to want to be better than what we’re emulating, which from a creative aspect, was an amazing journey for young, aspiring artists.”

However, the downside, he says, is that his musical “elders” do not see the commercial and financial benefits of being great.

From being the youngest singer at one of South Africa’s biggest nightclubs to then having to go into exile at the age of 16, Morake never anticipated that the story of The Lion King would be closely related to the story of a young Lebo M. Before he could be associated with one of the biggest of movies that Disney produced, he would first have to get his big break.

Enter Power of One.

When speaking to Morake about this, he grins.

About 30 years ago, a young and impressionable Morake had walked into a studio hoping to work on a movie not realizing that it would instead set the tone for his musical career.

In his mid-20s, Morake was hired as a coffee guy or barista at the Hilton Rosenthal Studio in Berlin, Germany.

He was serving coffee at the studio named after the music pioneer, Hilton Rosenthal, who was also the late South African musical legend Johnny Clegg’s manager and producer based in Los Angeles. But Morake’s life was just about to change.

“And his friend Hans Zimmer came to see Hilton,” Morake explains. “And I suspect very strongly, he wanted to collaborate with Johnny Clegg, who was not in the country.

“Hilton then simply said to Hans ‘you must try this kid and go to the studio’.”

Morake sips his coffee, reminiscing.

“I guess, in his mind, I was going to translate lyrics, but I ended up co-writing, performing, arranging and flying [back to South Africa] to set up to record the entire soundtrack choir, and I fell in love with doing that soundtrack.”

Power of One was released in 1992. The soundtrack was co-composed by award-winning composer Zimmer. This soundtrack inspired Zimmer to compose Disney’s 1994 classic The Lion King, which Zimmer wanted Morake to be a part of.

“For me, being South African, my ‘South African-ness’ is the epitome of the essence of who I am as an artist.”

“As a young man, you would think I would be nervous or apprehensive. But I’m glad I was not. I was hungry. I was ready. I was doing an assignment that came by default. I was just looking forward to getting paid, honestly,” Morake shrugs.

Multiple times, Morake has said that when it comes to the story of Simba (the main character in The Lion King), he felt as though it was a parallel journey for him.

“Literally, The Lion King film is as old as South Africa’s democracy,” Morake explains. “The journey of Simba who grows up in exile is the journey of Lebo M who grows up in exile. I didn’t grow up to become a king like Mufasa’s but my biggest project is The Lion King, whose storyline became very personal to me.”

When Morake was about 16 years old, he left for Maseru, the capital and largest city of Lesotho, with the intention to continue chasing his dream of becoming a musician. While there, he found that he could not return to South Africa, due to the apartheid regime, because he did not have a passport or any identity documents.

“Because of the power of the storyline, the characters were real human beings to me. Mufasa was Nelson Mandela. Simba was little Lebo to adult Lebo. Sarabi was Miriam Makeba. Scar was the apartheid regime,” he adds. “So, my lyrics and the melody for the soundtrack for The Lion King was inspired by the energy that was happening at home, and then I began going home while working on The Lion King.”

The Lion King in 1994 made $1.5 million in the opening weekend in the United States, which equates to over $2.7 million in 2021. Worldwide, the movie clocked in $986 million which today would be $1.71 billion. Morake took home a Grammy Award in 1995 in the category Best Instrumental Arrangement with Accompanying Vocals and also shared a Grammy with Zimmer for the song Circle of Life / Nants’ Inginyama.

Other than Zimmer, Morake got to work with big names in the industry such as Sir Elton John and Beyoncé (in the remake and live action version of The Lion King, which was released in 2019).

But outside of that, he has also played a big part in uplifting aspiring musicians in the industry over the years. Many have said that he is a visionary and has contributed to opening doors for many South Africans.

“As an aspiring film and music scorer, I learned a lot from him without him even knowing who I was. He is the guy that hired me for The Lion King and introduced me to people like Hans Zimmer and more, and the movie world in Hollywood,” says South African actor, singer and performer Brian Temba, best known for his role as Simba in the musical production of The Lion King.

“He is unselfish and he gives opportunity when he sees potential. I was the first South African Simba to be on an international stage in The Lion King in the United Kingdom, because he saw potential in me and gave me an opportunity. I’ll always be grateful to him for opening that door for me.

“He always had a word of encouragement for us and of course his jokes… We don’t get to see each other a lot, obviously because he is a busy man. But when we hook up all over the globe, it’s always a great experience and such an inspirational occasion,” says Lucas Senyatso, the South African bass player for The Lion King, the musical.

Throughout Morake’s career, The Lion King has had a special place in his heart at every step of his journey. When he helped score the Tony-nominated The Lion King‘s stage musical, he created new music and added pieces from Rhythm of the Pride Lands.

“You can’t say I am a jazz artist or a hip hop artist. My work is quite different. My genre of work is highly unusual for a black South African, particularly and especially in South Africa. But I’ve noticed around the world the idea that my work and career shaped itself this way is not a very usual thing for a South African township boy,” Morake concludes, finally downing his coffee and eager to get a few hours of sleep before another day of harmonic symphonies begin.