Slap fighting is a raw, visceral, little-known combat sport gaining momentum across South Africa. It’s not for the faint-hearted, underscoring the need for greater regulation, even as proponents are trying hard to formalize the sport.

In the pantheon of African sports, where football reigns supreme, rugby commands fierce loyalty, and athletics showcases raw talent, a new contender is emerging from the shadows – slap fighting, a visceral, no-frills combat sport where opponents take turns delivering open-handed blows to each other’s faces.

It’s fast carving out a space in Africa’s diverse sporting landscape. What began as a niche spectacle, propelled by viral videos and grassroots enthusiasm, is now gaining traction with South Africa leading the charge and whispers of interest echoing from Nigeria to Kenya.

The sport’s introduction to Africa coincided with a post-Covid pandemic hunger for powerful entertainment, and local organizers seized the moment.

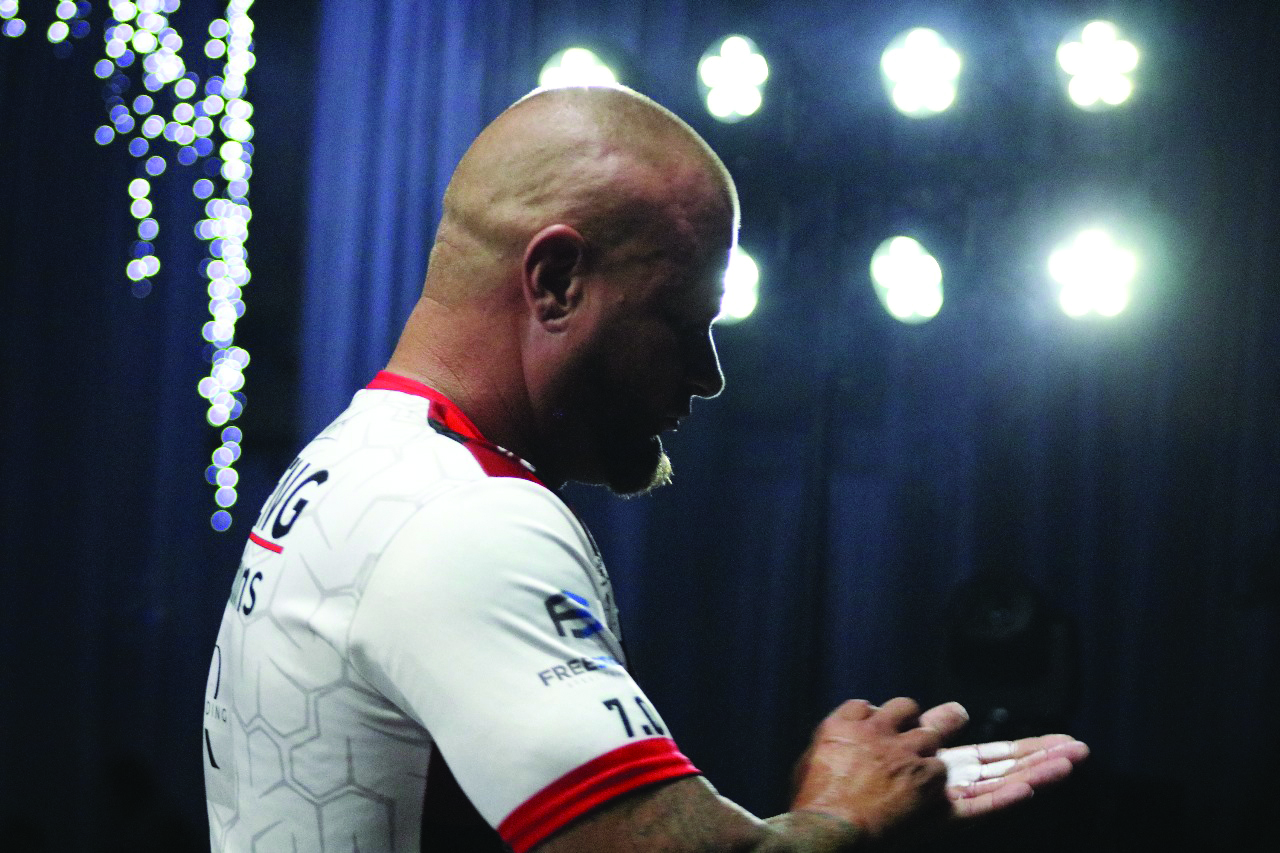

Founder and CEO of Ultimate Slap Fight South Africa, Bobby ‘The Punisher’ Krisch, discovered the sport while scrolling online.

Loading...

“In 2020, when we had the first lockdown, my son introduced me to YouTube, and I started looking at all these slap fights. I just fell in love with the sport. I had a bag at the back of my house and every day I would walk past it and slap it. The first time, I hurt myself, so I left it for two weeks. But there was nothing to do and when I went back to the bag and started hitting it again, I thought, ‘flip man, I can do this’.”

Slap fighting’s origins are often traced to Eastern Europe, particularly Russia, where videos of burly men slapping each other senseless went viral a decade before Krisch discovered the sport. It gained further prominence in the United States through promotions like Power Slap, led by Ultimate Fighting Championship president, Dana White, and Slap FIGHT Championship, which formalized rules and attracted millions of online viewers. By 2022, the sport had crossed oceans, and the South African Slap Fighting Association (SASFA) emerged as a pioneer, hosting its first events that year, while independent organizers like Krisch launched Punisher Slap Fighting.

“I’m a normal guy, maybe a little crazy in the head,” chuckles Krisch.

The sport’s simplicity is its strength: two competitors face off, often across a table or barrel, exchanging slaps until one flinches, falls, or is knocked out. Rules are minimal but strict–strikes must land on the cheek, delivered from shoulder height, with no defence allowed. Matches typically span three rounds, though knockouts can end them sooner. This raw format, paired with its accessibility, has fueled slap fighting’s appeal in Africa, where sports often thrive on passion rather than infrastructure.

Danie ‘Pitbull’ van Heerden, a former boxer and wrestler from Pretoria, South Africa, became the poster child after a 2022 TikTok video of him competing amassed over 17 million views. His subsequent invitation to Power Slap in Las Vegas, where he won by technical knockout, put South Africa on the global slap fighting map. In 2024, van Heerden reached the Power Slap 8 finals, facing off against super heavyweight champion Koa ‘Da Crazy Hawaiian’ Viernes, cementing his status as a trailblazer.

Across South Africa, local events are flourishing, creating a raucous atmosphere reminiscent of the country’s love for communal celebration. The Afrikaans term snotklap (a hard slap) is ingrained in local slang and tied to it are notions of toughness and settling scores. The sport showcases this and its inclusivity–requiring no gloves, pads, or extensive training–mirroring the accessibility of township football or stick-fighting, traditions that have long thrived without formal support.

With South Africa as its heart beat, the sport is spreading its tendrils across the continent. In Nigeria, a country with a rich boxing heritage and a burgeoning interest in combat sports, social media clips of informal slap contests have begun circulating. Lagos, with its vibrant street culture and appetite for spectacle, is a natural hub. In Kenya, where athletics dominates but wrestling enjoys a following, grassroots interest is emerging, spurred by online exposure to Power Slap and Slap FIGHT Championship. Ghana, too, with its history of physical contests like Dambe, a traditional Hausa boxing style, offers fertile ground for slap fighting’s raw energy.

The sport’s digital footprint is key to its continental growth. Platforms like TikTok and YouTube, where slap-fighting videos rack up millions of views, are widely accessible in Africa, even in rural areas with limited sports infrastructure. Van Heerden’s viral moment is a case in point; his 17 million views transcended borders, inspiring imitators from Johannesburg to Nairobi. As internet penetration grows, slap fighting’s low barrier to entry and high shareability positions it for a broader takeover.

In Africa, slap fighting’s rise also taps into the continent’s deep-rooted appreciation for physicality and spectacle. From Senegal’s Laamb wrestling to Ethiopia’s Donga stick fights, the continent has a history of combat sports that celebrate strength and endurance. Slap fighting, with its unadorned brutality and immediate outcomes, fits this mold.

Yet, the sport’s ascent is not without hurdles. Medical experts decry its safety, citing risks of concussions and brain injuries from undefended blows.

In 2021, Polish slap fighter, Artur Walczak, suffered a brain bleed. Krisch counters that of 107 fighters in his events, only two have suffered broken jaws, and medical personnel are always present. Still, scepticism persists, with critics calling it barbaric.

Regulation is another sticky point. Krisch is trying hard to legalize the sport in South Africa.

“It’s a process. It’s been two years and I pray we will be recognized and taken seriously. We are ordinary guys; many of us never had the opportunity to do boxing and mixed martial arts and wrestling. This is a sport for the normal working guy.”

Van Heerden has called for South African authorities to formalize slap fighting with a rulebook, arguing it would enhance safety and legitimacy. A 2019 draft amendment to the National Sport and Recreation Act could provide a framework, but progress is slow. Elsewhere in Africa, where sports governance is often underdeveloped, establishing oversight will be trickier. Without it, the sport risks remaining an underground novelty rather than a sanctioned discipline.

The sport’s future hinges on its ability to evolve. If it can marry Africa’s love of raw competition with a sustainable model, slap fighting might not just be a fad but a fixture–a slap heard from Cape Town will reverberate across the continent and be heard in Cairo.

Loading...