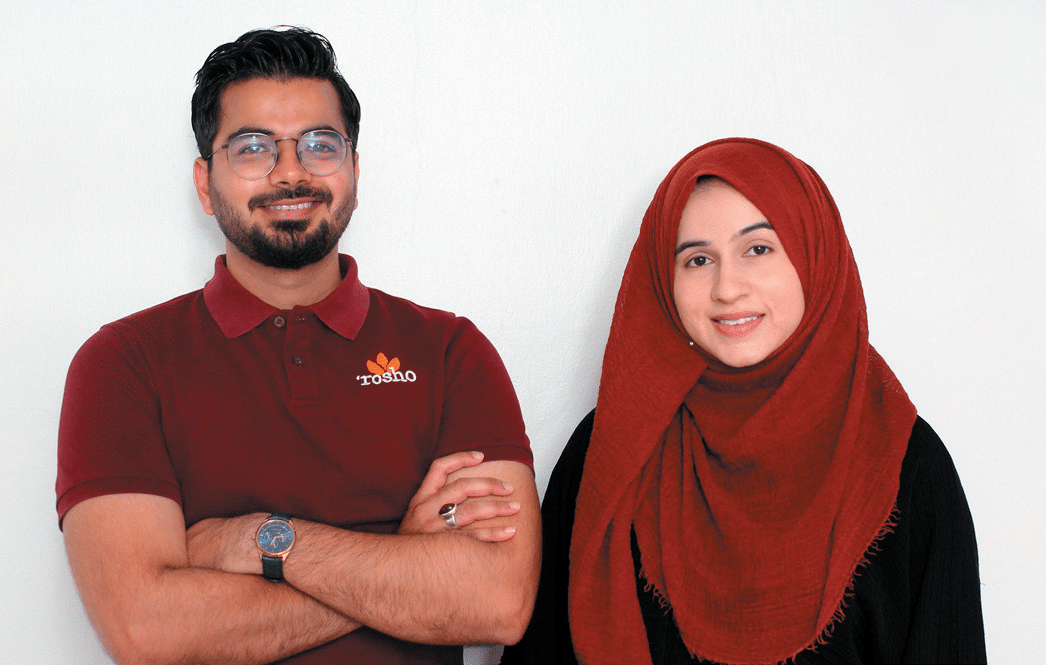

The couple bringing cashew butter to store shelves and healthy eating plans in Tanzania.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, Mohamedhussein and Sabiha Rashid were left with a large shipment of cashews they were expecting to export from Tanzania to the United Arab Emirates, as part of their maiden entrepreneurial venture together as husband and wife. Airports shut down cargo operations, and for weeks, the cashews had to be stored in their apartment in Dar es Salaam.

Sabiha had to find something to do with them.

Having watched numerous episodes of Shark Tank and attuned to entrepreneurial thinking, it struck her that she could convert them to cashew butter. Sabiha had gone vegan for a year while at university in England and had experienced first-hand the benefit of switching her food choices.

“I used to eat cashew butter, but I never thought of why nobody was making these things in Tanzania, although the country is one of the largest producers or growers of cashews globally,” she says.

So, out of her home kitchen, she started making the butter, as well as conceptualizing the product and packaging.

“I was experimenting and made lots of different flavors, made people taste it, but from day one, I said that if I’m starting a business, even if it’s a home business or just online, I need to make sure that what I’m putting out there is really amazing.”

She was pleasantly surprised by the response she received for the Instagram page she started on her product.

“It really caught on… it was the start of a small revolution, a healthy revolution.”

For three months, the small venture operated out of the couple’s apartment – it even blew up several food processors – but the demand grew and they had to soon find a dedicated space to enable production.

“PEOPLE DIDN’T UNDERSTAND THE CONCEPT OF CASHEW BUTTER – IT’S FOREIGN TO THEM… ALTHOUGH THE RAW MATERIALS ARE THERE, I THINK IT’S AN UNORGANIZED SECTOR THAT NEEDS A LOT OF WORK.”

Farmers’ markets helped gauge the public need, and it was time to formalize the business.

Three years down, and produced out of three factories, their product, ’rosho, a catchphrase derived from the Swahili word korosho for cashews, has grown.

But it wasn’t easy to get here. ’rosho only uses organic cashews, so processing has been expensive. Additionally, as food production is

largely underdeveloped in Tanzania, as in other parts of Africa, prices are high.

“We’ve really struggled with getting hold of good food technicians, microbiologists and all of these [professionals in different fields] that we require and also expertise in terms of machinery for production, packaging, etc…” rues Mohamedhussein.

’rosho’s conscious consumers have stayed supportive though. Says Sabiha: “There are tons of options imported [to Tanzania], but prices are very high and a lot of times, we get the leftovers, so they’re close to expiry. People are not happy with the quality they’re getting from the imported stuff… We are a better and local option.”

They have also had to ride out the initial skepticism. “People didn’t understand the concept of cashew butter – it’s foreign to them… So, although the raw materials are there, I think it’s an unorganized sector that needs a lot of work,” adds Mohamedhussein.

“I think as a company, for us, there has been so much problem- solving, so much innovation that we’ve had to do,” says Sabiha, “so much independent research, because there aren’t any bodies by the local government that you can reach out to for advice, although the government has been supportive. There have been

a number of trials and working with local engineers to innovate and be more efficient.” ’rosho also exports and within Tanzania, is popular among tourists for its local appeal. The company hopes to have a better impact on smallholder farmers. The founders say the factories currently employ only women and pay them 80% more than the minimum wage.

“That’s what we’ve tried to do, to give our customers a different sense of fulfillment when they’re buying from us,” says Mohamedhussein. “And to also sort of pave the path for other organizations and companies to come and do something more innovative