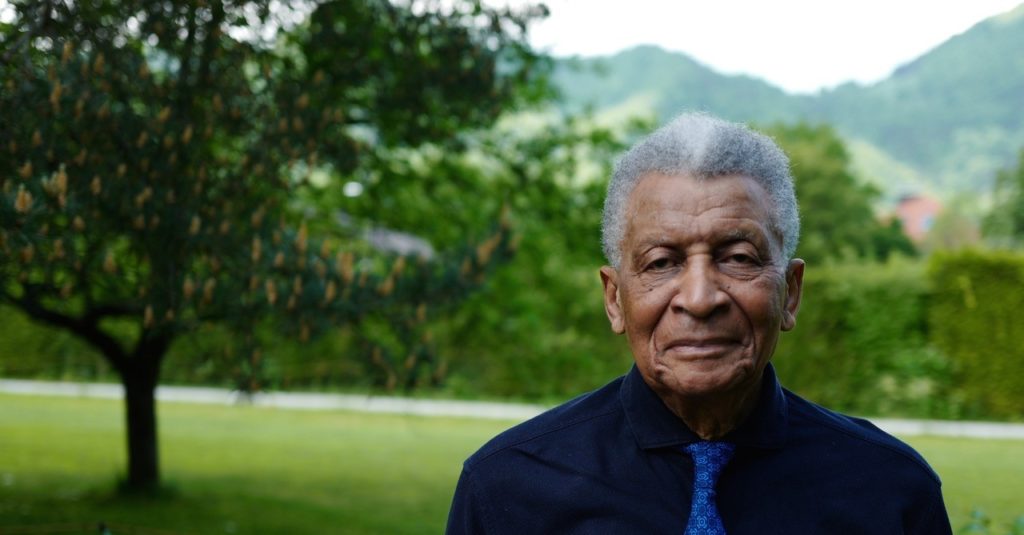

At the age of 88, South African pianist Abdullah Ibrahim’s music is as vital, creative and important as ever. The Germany-based composer, looking forward to the release of his latest album next year, shares more in this exclusive interview with FORBES AFRICA.

A gentle breeze plays with fresh soft green leaves in the early morning hush, clear notes float in the air as the maestro moves his fingers over the keys, conjuring moods and emotions. No matter the time of day, Abdullah Ibrahim has the power to transport me from the mundane world to one of music and dreams.

He lives in a little village south of Munich in Germany these days, his base between performances on concert stages which for the next few months will be in Finland, Germany, various cities in the United States, Canada, and France.

“This is what we do best as musicians, to be on the road and take our music to the people because it is virtually impossible for everybody to come to where we are,” he says on a Zoom call, looking at his partner Marina Umari, who is a medical doctor. “So this is part of our synergy in life. We travel, we take concerts globally. Of course Marina is really the anchor. She does all the behind-the-scenes work and presentation until the time that I get on stage.”

Saxophone players can pick up their instruments and travel. It is a bit more complicated if your instrument is a Fazioli grand piano.

“It’s a beautiful instrument, because it is excellent to work with,” he explains. “It is actually top of the range. And so we have an agreement with Fazioli that wherever I play, they will provide a grand piano.”

Now, at the age of 88, Ibrahim’s music is as vital, creative and important as ever.

Throughout our interview, he refers to the masters who have helped form him, and who still form him.

For many others, he is the guru, the master of the keyboard and composition.

It was Duke Ellington, the famous pianist and jazz orchestra leader, who heard Ibrahim play in Paris, in 1963, along with his Dollar Brand Trio, and led him to a recording contract and invitations to perform at key European festivals, on television and on radio.

Ibrahim has not played a concert in his native South Africa in seven years, and he is looking forward to his next visit, which will be coordinated with the release of his latest album around January next year. It was recently recorded with the new trio at the Barbican in London.

They recorded about five hours of music and this has to be curated into an album, which will be a combination of original compositions and pieces dedicated to jazz greats Ellington, John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk.

“This is our dedication to our masters and our mentors, wherever they are,” says Ibrahim.

Recently, he played at the Elbphilharmonie concert hall in Hamburg in Germany; a newspaper headline called the concert “a quiet prayer”. He says it is a remarkable venue, an intergrated music platform that offers a broad range of musical presentation. “It’s probably one of the most iconic music venues in the world that we are blessed to have.”

Although his latest tour is around Europe and North America, Ibrahim is no stranger to African shores. “Mozambique is very special, because of the interconnected legacy we have. Swaziland (now eSwatini) for example, I stayed there for about four or five years; in Senegal, I was resident for about three or four years. We had this excellent relationship that we established with the local culture and musicians. And of course with the drum culture. There was a drummer, Doudou N’Diaye Rose, and he had a drum choir of about 100 people, if not more – men and women.” Some years ago, Ibrahim took his New York band Ekaya to visit the Northern Cape province in South Africa and meet about 20 traditional local family groups.

“In Africa, the music legacy is passed on through families. We were there for about two days and these musicians from New York, they have masters’ degrees from Berkeley and such, and even today they still and such, and even today they still talk about it because they were totally blown away by the complexity of the music.

“Our traditional music is very, very complex compared, for example, to western music. Many people won’t agree with us of course, but that is the absolute truth. One of the things we implore our educators to do is to focus on African traditional music, because of its complexity and to integrate it into our education system.”

Having started piano lessons at the age of seven, and making his professional debut when he was 15, growing up in apartheid-era Cape Town, South Africa, Ibrahim was about 16 or 17 years old when he studied Indian music, the ragas (melodic elements) and talas (rhythmic structure).

“A lot of jazz musicians also gravitated towards that rhythmic and modal concept, because in Africa, all the music is modal and rhythmic, and there is a link.”

He believes that young Indian children grow up with complex music, which can then be translated into an understanding of mathematics, which in turn could have influenced the information technology boom in India. The same could be said of the education system in Japan, where young children are exposed to the complexities of tradition.

His Green Kalahari Project in South Africa makes a focus on traditional music implicit as a springboard to get into technology. When you deal with rhythm, he says, you deal with mathematics.

I ask him whether the appeal of jazz speaks to a niche audience and how diverse his audiences may be. He laughs and replies that he had once asked Ellington what his understanding was of jazz, to which Ellington replied: “Jazz, now let me see, we haven’t used that word since 1947.”

“If I had written a composition and dedicated it to my grandmother and she found out it was jazz, she would be very disappointed. So, this term that they affix to the music – all of us, we never called ourselves jazz musicians. It is a divisive mechanism and almost elitist because the roots of the music has always been community-based.”

It was the slave trade that took African tradition to the US. “This idea of improvisation is also a very basic method of

survival and of understanding. We have lost this footprint of improvisation, so we depend on playing safe. Because when you improvise you go into an area that you haven’t been before. So it’s very scary. So, I play a concert with a philharmonic orchestra, there are 90 musicians, and I say ‘Does anyone want to take a solo’? And they say ‘No’. Why not? ‘Well, we’re afraid’. Afraid of what? ‘Afraid of making a mistake’.

“From my understanding, there is no such thing as a mistake. Something occurs in life that you have to deal with and you have to find a resolution. So this is how we think of the music – like Thelonious Monk said ‘The piano ain’t got no wrong notes’.”

The term ‘jazz’ is a strange, strange concept, Ibrahim says. “Our audiences all over the world are not necessarily jazz audiences.

Breath and life is a gift for everybody regardless. We just know that we learn from our masses. Theyare unsung. They prefer to remain anonymous. So we learn from them what this is all about and how we should conduct ourselves. What shall we do with this gift God gave us? We invest in loss. That means we don’t expect anything in return. So this is what we present to the audience when we play the music.”

It takes a long time to achieve this, he explains.

“It is about more than music. It is about how I can be a better human being. And how I can dedicate my life to those close to me and to the community,” Ibrahim says.

There is deep sincerity in every note of his music. It is mesmerizing. Whether you listen to it in solitude on a gentle spring morning or by a night fire in winter. Or in a large concert hall anywhere in the world. Abdullah Ibrahim speaks to the soul.