Exploring the rich history of the Luangwa Valley in Zambia and the role of chieftaincy in the political and social fabric of the country.

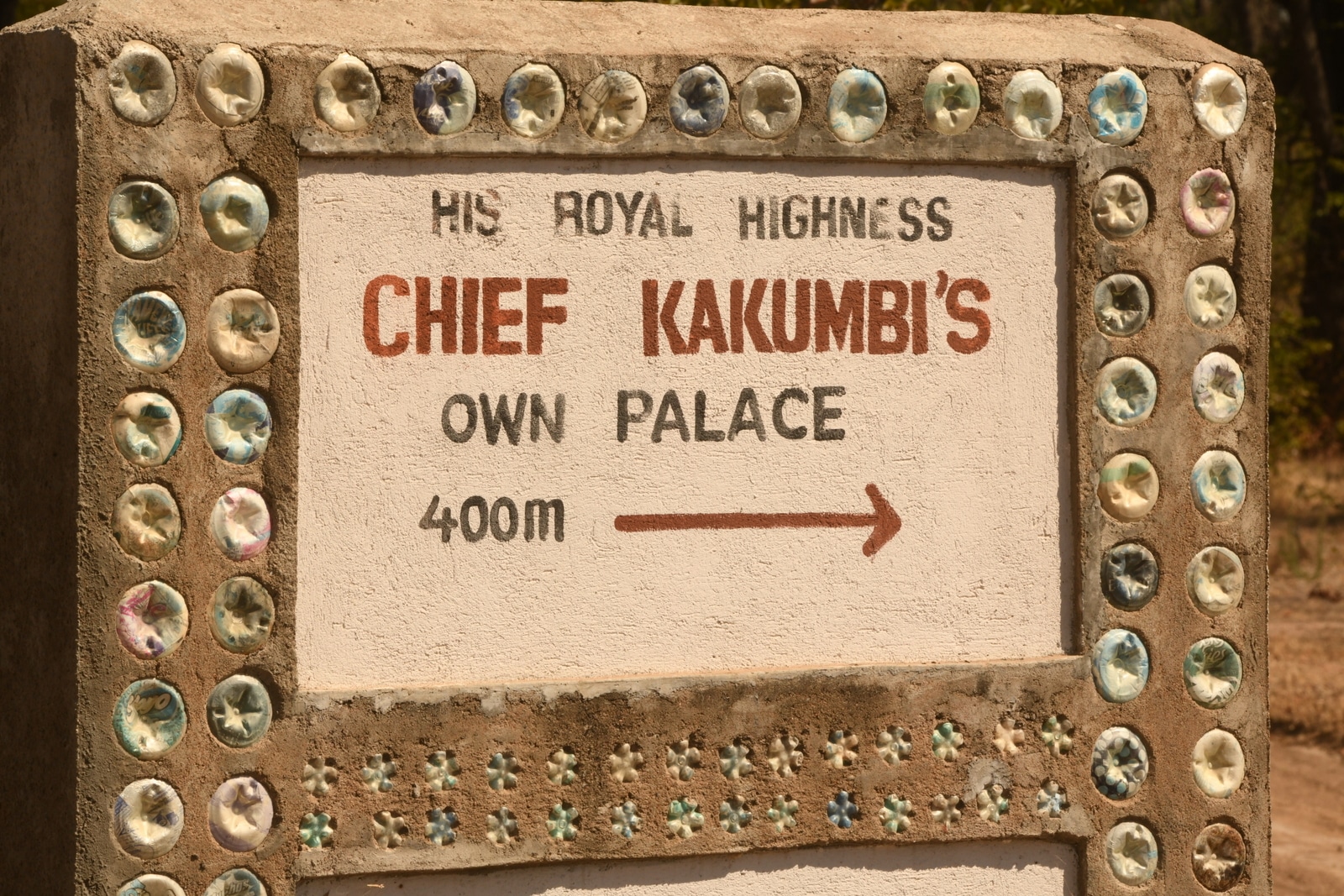

Driving past a sign that said ‘Chief Kakumbi’s Own Palace’ every day for over a week, in April 2023, inside the game management area of one of the premier wildlife conservation areas in Zambia, the South Luangwa National Park, made me curious about its presence.

A bit of investigation opened me up to a deeper understanding of Zambian chieftaincy and its role in the political and social fabric of the country. At the lodge where I was staying, everyone hailed from the Kunda tribe with Senior Chief Mambwee Che Nsefu Tenth (Smart Sonkhani Phiri) and Chief Kakumbi, one of the five Kunda chiefs in the south Luangwa, Mambwe District. Yet the locals spoke a dialect of Bantu found among the Bisa Ethnic Group of the Congo.

I immediately set about questioning senior members of the local Mfuwe village about their migration from the Congo into the Luangwa Valley (part of Northern Rhodesia prior to the 1960s) only to receive anecdotal stories of a migration in the 18th century. The Kunda were a large majority of the people living in the districts surrounding the park. When they spoke, I could hear a significant difference in their dialects.

“The indigenous people of South Luangwa National Park have three dialects, which are Chiŵetwe language from our original name Ŵetwe people before the change to Kunda people; Chikunda language from our current name – Kunda people and Kunda; Nsenga language which came about when we stayed with the Nsenga people during the Chikunda – Nsenga and the Ngoni – Kunda tribal wars respectively. The language of the Kunda people has undergone a serious metamorphosis,” Zulu Daniel, head of media at The Kunda Royal Establishment, elaborates to FORBES AFRICA.

During my trip, I soon determined that it was enslavement and internecine warfare that caused large migrations into the Luangwa Valley. The valley had been unpopulated due to its inability to support livestock with a high density of carnivores and because of the sleeping sickness disease. The Luangwa River flows into the Zambezi River where a plethora of land, gold, ivory, and enslaved people, among other things, incentivized the Portuguese crown to colonize the surrounding areas at that time, including what is now Mozambique and parts of Malawi. In the absence of a colonial army, Portuguese landlords hired individuals who voluntary sold themselves for economic survival and collectively they became the Chikunda.

These armies could be over 20,000-strong which helped the Portuguese subjugate local villages.

Utilizing the Chikunda warriors, the Portuguese raided nearby villages for the enslaved individuals and ivory to sell to Swahili and Arab traders from Zanzibar.

The Kunda moved to the Luangwa Valley in the 18th century after local tribal warfare among the Bisa people of the Luba Kingdom of the Congo.

“The Kunda split from the Bisa in around 1840s. The leader of the Kunda, who chose to secede from his father was known as Mambwee. The royal clans are Chulu for the Senior Chief Mambwee Che Nsefu, Chief Mambwee Malama, Chief Mambwee Mnkhanya and Chief Mambwee Che Jumbe, Mbawo Clan for Chief Mambwee Kakumbi Chief Sandwe of Lusangazi District and Sakala clan for Chieftainess Mambwee Msoro. Kakumbi and Msoro are in-laws who became Kunda Chiefs by marrying the royal women from the Chulu clan in the late 1800s,” says Daniel, throwing more light on the history and legend of the region.

“The migration from Bisaland concerns Bisa Chief Chaŵala Makumba. Chief Makumba had ordered that all male children be put to death at birth so that there was no threat to his authority as chief. One woman, Kaŵa Ciloŵa, had given birth to three daughters and then produced a son. This son was killed. Again, she became pregnant, producing another son who was also killed. Towards the end of her next pregnancy, she went into hiding in the forest and, after producing a son, took him to a neighboring village where Chief Mwane, a relative of her husband lived. There, the son was named Mambwee and there he grew to become a man. After hearing his life story, Mambwee decided to leave the realm of Chaŵala Makumba, gathered his people and moved east.”

The Kunda settled in a harsh area without the ability to raise livestock in the Luangwa Valley. Their peace was short-lived as they too were enslaved. This led the Kunda to disperse all over the Luangwa Valley for safety. As the Portuguese colonies crumbled in the 20th century, the Chikunda formed alliances with the Kunda and settled in the valley.

The militarization of the region of today’s KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa by Shaka Zulu, whose quest to consolidate his empire in the late 19th century, forced Ngoni residents of Swaziland to flee north into the Luangwa Valley, thereby putting pressure on the already-settled Kunda and Chikunda. The Ngoni were fierce warriors and soon started raiding both Chikunda and Kunda villages for enslaved people, which was the main economic driver at the time. The Kunda started off as pastoralists but were primarily hunters.

“The Kunda people fought their own wars and defended themselves,” adds Daniel.

“It’s important to make mention though that the Kakumbi Chieftaincy shared great history with the Chikunda people as they did a lot of hunting together [with] the first Chief Mambwee Kakumbi Loŵe Mungu up until the Chikunda people were chased away from South Luangwa Valley by Kunda warriors from Msoro Chiefdom, under the leadership of Makoleka and Mphandika who were the sons of Chief Mambwee Msoro then.”

With the arrival of the British and the formation of Northern Rhodesia and the Nyasaland colony, the war with Ngoni people was won by the British, and tribal peace declared in Northern Rhodesia.

With independence obtained from the British in 1964, the new country of Zambia was born, made from parcels of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland, the former name for colonial Malawi.

Today, the Government of Zambia, according to Daniel, recognizes four Paramount Chiefs, 43 Senior Chiefs and 241 Chiefs, summing up to 287 traditional leaders from 72 ethnic groups, 10 provinces and 72 districts.

Thus, Chief Kakumbi and Chief Jumbe of the Kunda people, in particular, own vast tracts of land along the South Luangwa National Park these days assist in game management, sustainable development and in the mediation of disputes and conflicts among the residents.

My attempt to meet Chief Kakumbi one Saturday – the day he meets with his people in the palace – narrowly failed since he had to attend a parliamentary meeting in Lusaka, Zambia’s capital. My homage – a chicken (given as a gift or sign of respect) – did not make it to his kitchen. A casual sign by the roadside revealed so much of the rich history of the Zambezi valley, where the great explorer David Livingstone began missions and later exposed and campaigned against enslavement, and the darkest chapter of humanity.

Note: This article was updated on March 20, 2024 to include additional facts and information about the Kunda tribe and the history of Zambia, and commentary from The Kunda Royal Establishment.