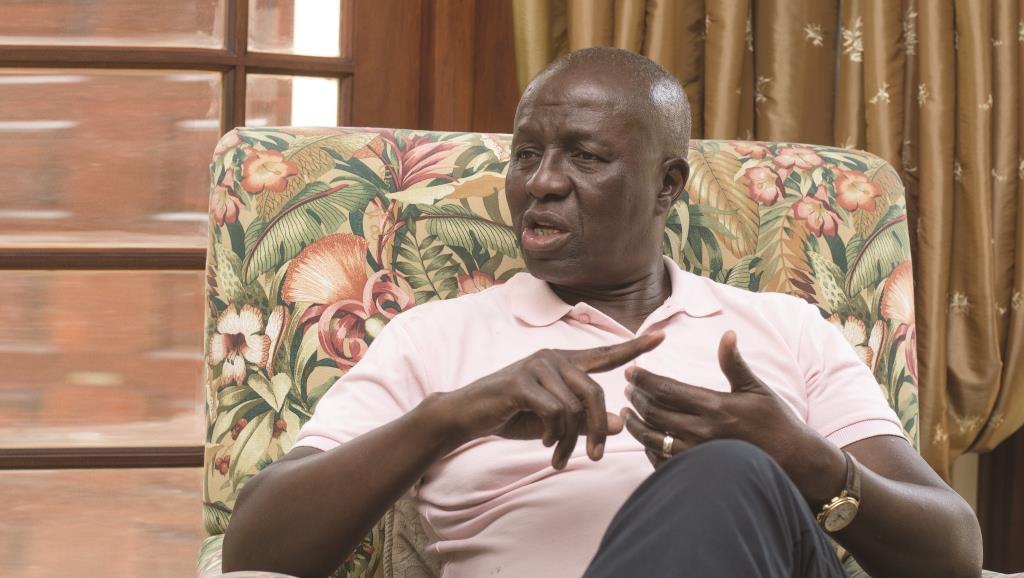

We meet Dikgang Moseneke exactly three years after Nelson Mandela died on December 5, 2013. Dikgang, the retired deputy chief justice and the executor of Mandela’s will, is in a pink Polo golf-shirt, navy chinos and matching loafers; reclining in a floral sofa in his home study in Pretoria, South Africa’s capital city. It may be three years after Mandela passed away, but Moseneke shows deep emotion as he relives the day the man, who mentored him on Robben Island, left him.

Upon entering Moseneke’s home, two large portraits of Mandela and Robert Sobukwe, the founding president of the Pan Africanist Congress and a fellow Robben Island prisoner, greet you. On the day Mandela passed on, Moseneke was at a year-end dinner for judges and his phone was off.

“Towards the end of the dinner I switched on my phone. There were these several messages from Mama Graca Machel (his wife) and Bongi Mkhabela (CEO of the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund), and they were all saying ‘Tata is gasping. You have to be here.’ I ran out of the dinner to [Mandela’s] house in Houghton. And the old man had just surrendered, he had just passed on. And Mama Graca was seated there crying and on the side was [Mandela’s daughter] Makaziwe. It was terrible. It was like a father who had passed on. I have my own father of course, but he was a father on Robben Island,” he says.

Politics brought them together a lifetime ago. By the age of 13, in high school, Moseneke, born in Atteridgeville, a township near Pretoria, was engrossed in the African Students Union of South Africa (ASUSA) and later the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). It was a risky passion under apartheid.

“Our headmaster at Banareng (Primary School), Mr Ramopo, had related to us the fables of James Emman Kwegyir Aggrey, a champion of African nationalism, and in 1960 I had been horrified by the Sharpeville (massacre) corpses I had seen on the pages of the newspapers we read daily,” he says.

The headmaster had planted a seed in young minds.

“I hated oppression. I hated the difference and I still hate it now. I dedicated my life in trying to advance equality, to get African people out of bondage, out of oppression. The fact that we have failed to do it now makes me angry. Too few of us have come out of that terrible economic situation for African people. Even then, when I was growing up, I could see the differences between the suburbs and townships, the lawn and the dust, differences in our schools, we had great teachers but the facilities were inferior. Young people have a deep sense of what’s right and wrong.”

It was at the crack of dawn, in March 1963, when Moseneke was at the mercy of a dozen rough policemen who kicked open his front door, ransacked the house and took him away.

“Mercifully, they missed all the banned literature and leaflets that were meant to rouse the populace into a revolt that morning. I froze with fear, but I didn’t cry… They cuffed my arms behind my body. I was under arrest for terrorism, they told my crying mother, but they were not permitted to tell where I would be kept. They blindfolded me and we sped off into the darkness,” Moseneke says.

He faced a gruelling trial on charges of sabotage and treason, and spent nearly a year in solitary confinement in a Pretoria prison.

In July 1963, in the winter rain and piercing wind, Moseneke paid the price for his principles when the guilty verdict came out. The 15-year-old Moseneke and other political prisoners were chained in pairs and cramped in the back of a police van all the way from Pretoria to Cape Town, where they were ferried to Robben Island. In oversized prison clothes, he started a 10-year sentence.

Despite Moseneke’s group affiliating to the PAC, a breakaway of Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC), senior prisoners from the ANC and other banned political formations took the youngsters under their wing. Between toiling in the prison quarry, Moseneke studied English, political science and law through the University of South Africa. He co-founded the Makana Football Association, a prison league.

On the day he was released in 1973, grinning policemen came to his home and told him he was banned for another five years. This meant he was on curfew and couldn’t mix with more than one person at a time.

Mandela remained in prison but the bond between the two was strengthened.

“In fact, I went to see Mandela in Victor Verster Prison before he was released. I did a lot of assignments for him, very critical assignments in his life. And he relied on me in a variety of fronts; for example Mandela asking me to write the interim Constitution.”

Upon retirement in 2016, Moseneke published a book called My Own Liberator: A Memoir, in which he talks of his political rite of passage and time with Mandela.

“I have a chapter in the book where he says ‘Dikgang, I am glad I have found you’. He traced me down to the Kruger National Park, I was in the Malelane Lodge, hiding, and he said ‘Well, Dikgang I am glad I found you, you must come and run the elections’, so I became the deputy of the IEC (Independent Electoral Commission). I made it quite clear I was not going to run for a political office. I am going to become a lawyer, and possibly a judge, but not a political leader.”

Indeed, Moseneke was true to his word. He stayed as a lawyer. Moseneke and George Bizos, the lawyer that defended Mandela in the Rivonia Trial, represented Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, his ex-wife, when she appeared before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1997, for the abduction and murder of a 14-year-old Stompie Seipei. Moseneke was on Mandela’s defence team when he divorced Madikizela-Mandela in 1996. Madikizela-Mandela hired Moseneke when she was fired by Mandela in Parliament for visiting Ghana without permission.

“I won that case against him. Winnie was reinstated. But that didn’t tear us apart, it got us even closer. When the Mandela Children’s Fund was formed, he asked me to chair it, which I did for 16 years non-stop. It was one of his first loves, the children. That’s why we opened the hospital which was conceived under my leadership, and Bongi Mkhabela ran with it. I retired from the Children’s Fund and allowed for a new leader. Otherwise, I would have been like President Mugabe and stayed on forever.”

“This day, I am still the executor of the will. Mandela said: ‘Dikgang will you look after me when I am not here?’ It was big ask, from a big man. I said ‘yes Tata’.”

Moseneke is one man who can say he was close to three South African presidents but he cannot be accused of being a lackey to the powerful.

When Thabo Mbeki took over from Mandela in 1999, he appointed Moseneke to be the judge of the Constitutional Court and as Deputy Chief Justice, in 2005, a position he retired in.

“He asked me to go to Zimbabwe to monitor the (2002) elections; I wrote a report which Mbeki didn’t quite like. It wasn’t made public until the courts ordered that it be revealed. I said the elections weren’t free and fair. Even though we were close but he came to know that Moseneke was independent,” says Moseneke.

Mbeki, who wrote the foreword for his book, had told Moseneke if he had not been recalled in 2007, he would have made him the chief justice.

“Our world view has a lot in common, he’s by and large an Africanist, he believes in African renaissance and the greatness of African people, and the need for them to rise again. I believe in the