Friendships are sometimes forged in the most unlikely of circumstances. Against the backdrop of legalized racism, apartheid South Africa was one such circumstance. During its darkest years one could be forgiven when reading a “white” newspaper for thinking black people did not exist. And yet it was in this environment that Nelson Mandela and a young, promising, white journalist forged a friendship that would last a lifetime.

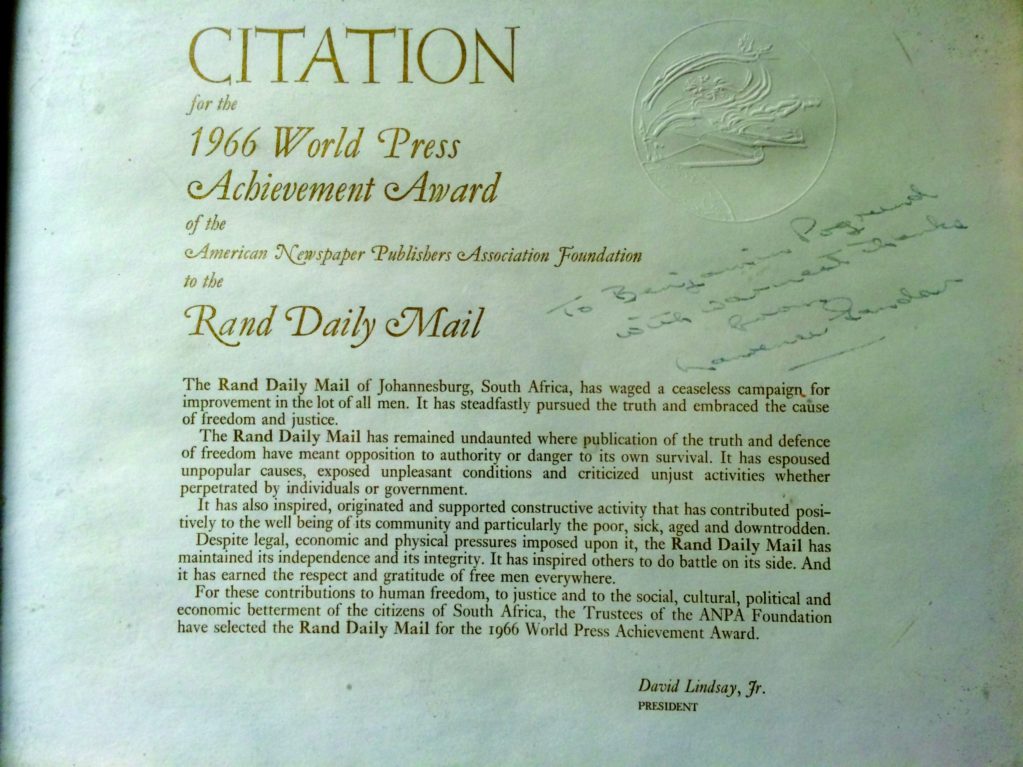

Benjamin Pogrund, 82, sits in his Jerusalem apartment, smiling. The veteran journalist and a pioneer of black reporting at the then all-white daily newspaper, the Rand Daily Mail, joined the press as a missionary which, he’s quick to admit, is a very bad thing for a journalist.

At the time, black South Africans were not featured in the mainstream press. There were some stories about court cases, riots or mine accidents where black people were mentioned but it was “crazy” how they were ignored, remembers Pogrund. He took it upon himself to change things.

“Benjy Boy”, as Mandela called him, describes his success as being in the right place at the right time. He says the Rand Daily Mail was an awful paper when he joined, with a new editor, Laurence Gandar, who luckily had the same political views as Pogrund.

Loading...

“He liked what I wanted to do, because I started covering black politics, which hadn’t been done before,” says Pogrund and a friendship between the junior reporter and senior editor soon flourished.

But covering black South African life meant being ostracized at work and in the Jewish community to which Pogrund belonged.

“I was dealing with an all-white paper,” he explains. “So I was like a cat being dragged in from the night, they hated me.”

At the time the Jewish community was split, between businessmen who surrendered to apartheid so their businesses would succeed, and liberals.

Soon Pogrund began covering everything from housing, education and jobs, to pass laws. And through the years he became a confidant for the leaders of black resistance, among them Mandela.

The two had countless secret meetings. While most of the police force would be out hunting for Mandela, he’d show up on a dark street corner disguised with worker’s overalls to meet Pogrund.

“His followers probably wanted to cut my throat, they probably thought I’d trapped him and I’d hand him over… but we got away with it,” he chuckles.

For Pogrund, it was Mandela’s generosity of spirit that always stood out. He sums it up with one specific story – Mandela called for a major strike against the government. The day came and the government issued a statement saying it had failed. The Rand Daily Mail ran with the headline “Strike Has Failed, Says Government,” without consulting Pogrund. The strike itself didn’t go as planned but it wasn’t the failure the government claimed it was. Hundreds of thousands of workers did stay home, but when they read the newspaper, a paper which they respected, they were scared of being dismissed, and went to work.

Pogrund remembers sitting in his office, feeling miserable, when his phone rang.

“And there’s Mandela’s warm, cheery voice, and I started stuttering an excuse, ‘Nelson, I’m sorry we screwed up’… He said to me, ‘It’s okay Benjy boy, I know it wasn’t your fault.’ I loved that man ever since.”

Pogrund and Mandela’s relationship extended beyond the clandestine meetings. While still in prison, Mandela insisted that Benjy Boy bring his second wife, Anne, for a visit. He even sent a card to their son Gideon for his bar mitzvah – a coming-of-age ceremony in Jewish tradition.

As for the Mandelas, Pogrund jokes that he was their Jewish uncle, telling how he helped Mandela’s daughter, Makaziwe, get into an American university.

“Over the years, now and again I’d go and visit her regularly, and she’d say to me, ‘please get my father off my back, he’s driving me crazy. He wants me to go to Harvard, I don’t want to go Harvard, I’m happy here at UMass Amherst!’’

Pogrund eventually found sanctuary in Britain where he worked on Fleet Street. From there he went to America and onwards to Israel to help build the Yakar Center for Social Concern. He’s been here almost two decades.

But ties with South Africa run deep and although he believes a lot has been accomplished, he is sad and angry by what hasn’t been.

“The country now has clean water and more access to healthcare, jobs, everything like that. Everything is better… but on the other hand, the failure is colossal.”

The reasons include government corruption, the heritage of apartheid and the currency. But most importantly – education.

“The majority of schools are described as dysfunctional, lacking ordinary toilets, electricity, blackboards, desks, books.”

Pogrund looks at how countries like Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan used education to come out of poverty, but says South Africa just isn’t getting there.

“There are a lot of people doing well. But the bottom people have it bad, and this carries over into people going to universities who shouldn’t be there… they haven’t achieved enough.”

And his beloved profession has become a disappointment.

“Under apartheid, we had some very committed, very good journalists. People didn’t sit around discussing press freedom, they just did it. They had a commitment, they got on with it. But whereas we were unable to exercise our full rights, now the opposite is true – and there isn’t the competence to do it.”

For a man of many words, there’s one thing he can’t get himself to talk about: Mandela’s last days. The laughter stops and sadness takes over; at times it’s even difficult to hear him.

“He had a miserable last couple of years. Miserable. It’s too personal.”

In the just over two years since Mandela passed away, Pogrund is more convinced than ever that the world desperately needs another Mandela.

“Israel is in a need of another Nelson Mandela, England is in need, every damn country is in need of a Nelson Mandela.”

Sadly, he is gone.

Loading...