David Adjaye believes that African skylines are set for an explosion of growth as the continent’s resurgent economies look for new expressions of their increasing potency and self-confidence.

Speaking at his studio in North London, the architect says that the continent needs to define its own vision for urbanization and ensure that its architectural revolution reflects Africa’s cultural, geographical and climatic contexts.

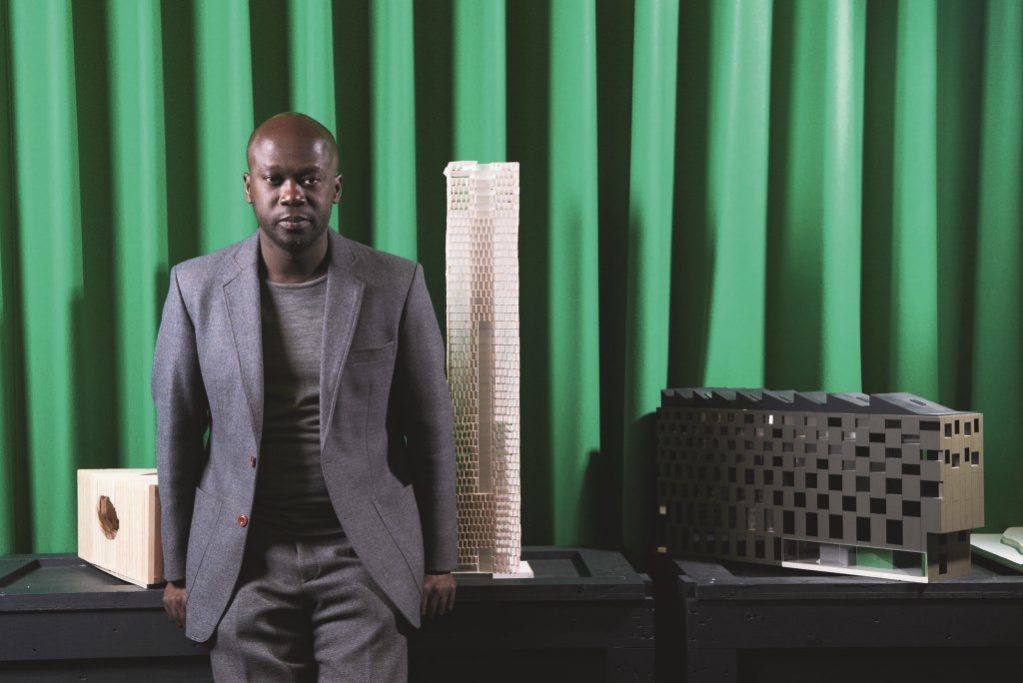

Born in Tanzania to Ghanaian parents, Adjaye traveled extensively in his youth, following his father’s diplomatic career through Africa and the Middle East. It was that exposure that was to later inform his work when, after studying fine art, he found architecture and became fascinated by the relationship between buildings and their environment.

Nobel Peace Center, Oslo. The Canopy is a temporary installation by David Adjaye that serves as a gateway between Oslo City Hall, where the Peace Prize Ceremony takes place, and the Nobel Peace Center.

“I realized that by having been brought up in very different contexts—cultural, religious and social contexts—I had somehow developed an appetite for learning more about how the built environment worked with that, and how it reflected that architecture in its human sense.”

Today, Adjaye is one of the world’s leading architects—in 2007 he received the Order of the British Empire for his services to architecture. His portfolio includes the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo and the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC, which is scheduled for completion in 2015.

For a 2010 exhibition at the Design Museum in London, Adjaye traveled to cities across Africa, photographing the buildings which, although in varying states of development or decay, show startling commonality.

Today Adjaye runs through his own potted history of African architecture: Colonial builders erased much of the pre-existing urban culture in Africa, replacing it with tropical versions of European architecture. Upon independence, new leaders embraced a vision of the future that was still largely European.

“I think the early leaders on the continent felt that modernity was the way to embrace or celebrate a sort of new world of empowerment for their nations. So you find a lot of modernist experiments, but modernist experiments that could not avoid the specificity of the geography and the climate. So you have what I call a kind of tropical modernism,” he says.

When the money and ambition began to wear thin, this modernism was replaced by economic pragmatism, driven by international donors who made their architectural choices based on their own financial imperative, and using their own approved contractors and designers.

National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC.

“So you have very odd late ’70s early ’80s buildings that sort of appear, that have nothing to do with the context; they’re just blips,” Adjaye says.

With debt relief and the mineral-driven boom of the late 1990s, which gathered pace in the early years of the new century, African leaders began a new drive for modernity. With this financial independence and growing economic self-confidence has come a stronger sense of cultural identity across the continent, which is manifested in the creative arts.

“I think you see it in literature, fine arts, performing arts and architecture, they’re all in line. They all lead the image of what nations want to project of themselves.

“This image of most of the countries on the continent getting rid of their debt and suddenly discovering vast minerals and negotiating this, means that there is an opportunity to really explore the idea of modernity for these nations. And architecture comes to the forefront of that, because architecture is the image of the city and the future. Architecture is the image of the city as it sees itself. The story of the city is written in books, but it’s also written in buildings.”

The notion of buildings-as-ambassadors has gained currency in the past decade with the successful reinvention of the Emirates of Abu Dhabi, Dubai and the state of Qatar.

“It totally worked,” Adjaye says. “It gave the Emirates a skyline. For my father’s generation, the Emirates was a horrible desert and a place you never went to.”

Where the Emirates initially failed, he says, was specifying what its own version of modernity was. It is a trap he is keen for Africa to avoid. Buildings need to exist in their context, rather than just mimic the current, internationally dictated interpretation of Western modernity.

“I think if there is much more criticality about the way in which buildings are built to their climate, you get a much more unique skyline,” he says. “That doesn’t require more money, it just requires more desire on the part of the patrons to insist on a response that makes things specific, rather than insisting on an approach which is just novel.”

Africa’s modernity, Adjaye says, should be dictated by the same geographic features that defined its early cultures. This means ignoring the artificially imposed national boundaries and shaping regional identities from the unifying climates and cultures across the continent, but also avoiding the “colonial trap” of what he calls “Disney-fication” of culture.

For inspiration, Adjaye looks to New York.

“I love the Rockefeller Center. It’s not a cheap building, but it’s an efficient building. It’s a building that strove to understand the time that it was in, which was the ’30s… It talked about density in the city, it talked about networks, it talked about interconnectivity. It talked about living in the heart of the city. It gave a model which was not iconic in terms of imagery but iconic in terms of place, and it’s still a fundamental part of New York.”

That specificity of place and time has created a building that is more than functional—an artifact that helps to define the city it is in.

“There’s something compelling about coming over that bridge from Brooklyn or Newark, New Jersey, and seeing that skyline. It’s like… it’s so powerful. It’s original. That’s the vision we need in Africa. What is the model of living in Africa that nowhere else in the world you can have? The person who cracks that, cracks the game. Not the person who imports the model that we’ve seen before.

New York City, Rockefeller Center, GE Building, viewed from 5th Avenue.

“You’ve got to make a model that makes people say ‘I want to go to that city in Africa because it’s just so great. The life there is something I can’t have in London. It’s contemporary, I can have my life there, but it’s completely unique.’ That’s a hell of a thing.”