August 16 2012. Thirty-four miners, mostly employed by Lonmin, on strike for a wage hike, were shot and killed by South African police in Marikana in Rustenburg, South Africa.

The men who died left behind wives and children who have suffered both pain and poverty in their loss.

FORBES WOMAN AFRICA visited six young widows who have now relocated to Marikana to work and be their families’ sole bread-winners. Most of them are cleaners earning a little more than their husbands did, living in a hostel at the Vulindlela Training Institute (that trains miners). They all share the same anger at the cops who shot down their men and changed their lives forever.

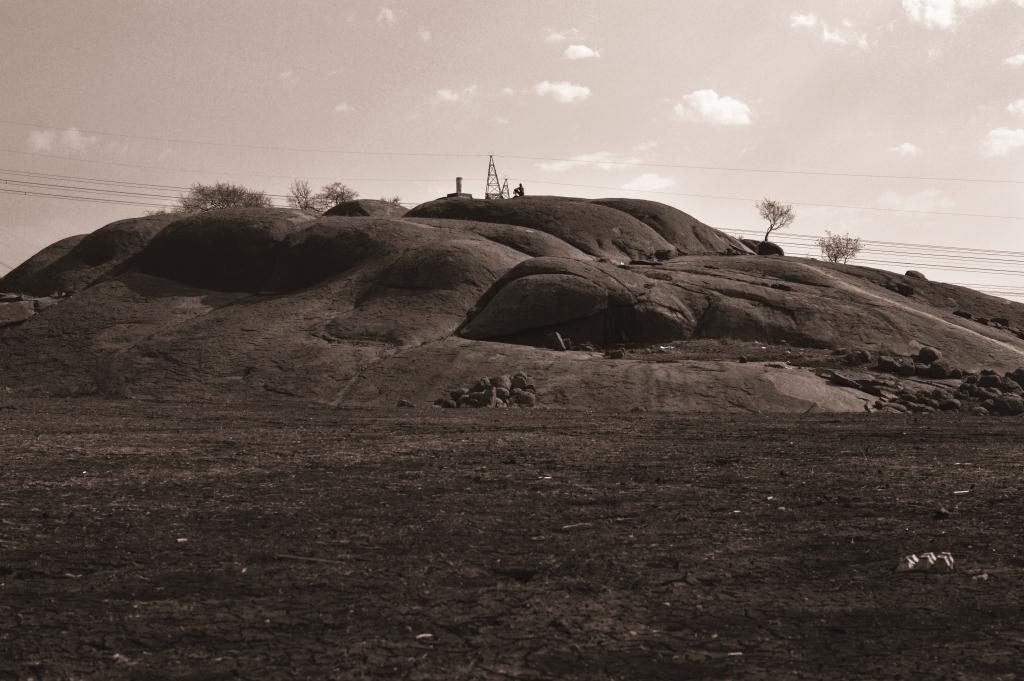

Walking around Vulindlela, you soon realize most of those affected by the Marikana massacre are resident in this area. It is now a community of the inconsolable, as they go about their lives at work or at school, returning to neighbourly chats, and time alone reflecting their fate.

They speak in chaste isiXhosa and seSotho, languages tough for an average Johannesburg-born city dweller like me to comprehend. But their emotions convey more than any language can ever do, as these pictures that follow show.

Double tragedy

When Lesotho-born Mathabile Monesa, 25, lost her husband Khanane Elias Monesa that fateful day in Marikana, she was pregnant. At the time, she was living with her in-laws in Lesotho and her husband was the sole provider to a family of nine.

There was more tragedy in store.

Weeks after his death, she was admitted to hospital and lost their unborn child, a son. Doctors put it down to stress and depression.

“It was painful knowing that our provider was killed, knowing that I now have to put food on the table for the family with the money I made from sewing,” says Monesa.

Monesa hopes the R12,500 ($900) the miners were fighting for will also be given to the widows in the future.

Loved dearly, missed sorely

Just two rooms from Monesa’s, 35-year-old Nombulelo Ntongo from the Eastern Cape is on the phone with her seven-year-old daughter, who suffers epilepsy, and who she only sees during the Easter break and the December holidays.

Before losing her husband Bongani Nqongophele, she lived with her mother-in-law, daughter and five other family members in the Eastern Cape.

“After the death of Bongani, it was hard, our child was sick and I couldn’t take her to the doctor; she was small and epileptic and I couldn’t even buy food and clothes, nobody could take Bongani’s place because he was the only one who could take care of us,” she says.

Today, Ntongo sends money home to her mother-in-law for food and doctor fees, as well as for her daughter’s school uniform. Lonmin pays the school fees.

“If I had an alternative, I would leave this job and go back home. I’m not here because I want to, I’m here because I don’t have a choice; it is not nice living here and the child living back home.”

Nqongophele’s memory lives on. In Ntongo’s little bedroom are pictures and messages from her daughter pasted on the door. Nqongophele was loved dearly by his family.

‘He was left to die’

Rebuselelitsoe Lefulebe, 26, from Lesotho and speaking Xhosa, can’t supress her incessant tears, even now, three years after her husband Bongani Mdze’s death in the Marikana massacre. She remembers the day like it was yesterday, when she was visiting him.

“He died upon arrival at hospital, he was left for more than an hour at the scene after he was shot; he was left to die; if he had received help, he would still be alive,” says Lefulebe.

Lefulebe recalls how Mdze had looked after his sister’s three children and his own child with his meager pay.

“Today, the children aren’t happy living with relatives back home; they tell me everything and mention things are not the same since daddy has gone.”

Mdze had applied and passed the test for a supervisor position. Had he been alive, Mdze would have earned more than Lefulebe does now.

The mother far away

A few blocks away, we visit a mother of five, Nosakhe Nokamba. Today, she is her family’s only bread-winner. Currently living with two of her children, she sends money home to the care-taker to feed the three others who she also sends to school.

When her husband Ntandazo died, he was 36, leaving young children.

“It’s been hard around here, when I sit alone and think you know you are not at home and the only reason I’m here is because my husband left us, and now I’m separated from our children,” says Nokamba.

‘Where is daddy?’

Twenty nine-year-old Nosihle Ngweyi is miner Michael Ngweyi’s widow. Before his death, Ngweyi lived with their two children in the Eastern Cape.

“The challenges I’m facing are the children. They ask questions I sometimes may not be able to answer. They would ask, ‘where is daddy? When is he coming home?’ I would respond by telling them not to ask that question again because daddy is not coming home,” says Ngweyi painfully.

She says after her husband’s death, she was left with a lot of responsibility and an incomplete house with only a fence. With the compensation she received after the tragedy, she built a two-room house and lived there.

Ngweyi’s therapy is school. She says after work she would rather go to school and learn and be busy, rather than dwell on the past.

‘I have to sustain them’

Masebolai Liau was married to Janfeke Liau and they were both from Lesotho. Today, she lives far away from her village, her home and the cows and sheep she has left with care-takers she remunerates every month.

She knows not in what state her livestock is.

“I try but it’s hard. I do this because I have to sustain the people and the belongings my husband left. His family, our family, our farmers and the farm, he could do this all by himself,” she says.

Liau wishes for a support group so people can express their feelings and find comfort in each other’s pain.