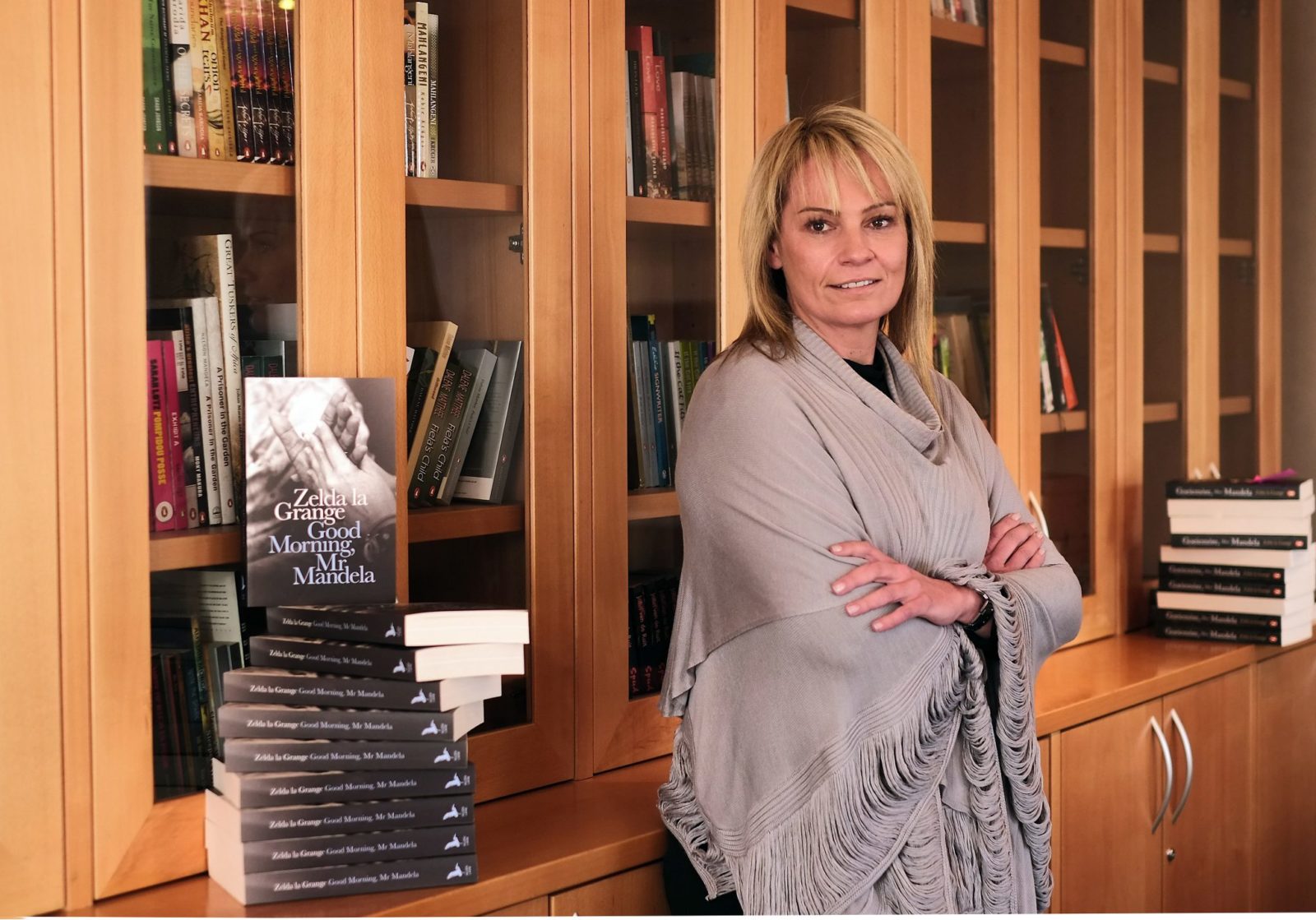

At the well-attended launch of her book Good Morning, Mr Mandela in Johannesburg in June, Zelda la Grange, Nelson Mandela’s trusted aide who he called ‘Zeldina’, was introduced “as the person who walked in the same steps as one of the greatest legends”. Archbishop Desmond Tutu said in a televized message on the occasion: “Your utter devotion to Madiba was so obvious to anyone…In many ways, it was a symbol of hope for the new relationships in our country.”

La Grange says ‘Khulu’ (grandfather) or Madiba always knew she would write a book. The Afrikaner, who was brought up in apartheid South Africa, started as a typist in the office of the first democratically elected South African President in 1994 at the age of 23, going on to work with Mandela in various capacities for 19 years. She started penning down her thoughts in 2009, “not for the purpose of it becoming a book, but to offload memories”.

“It’s a personal memoir and I want people to read the book and be inspired by my change,” said la Grange, ahead of the launch, when we caught up with her for more:

Can you describe your first meeting with

Madiba in 1994 at the Union Buildings?

I bumped into him, he extended his hand and I said ‘Good morning, Mr Mandela’. That was the turning point of my life.

He broke all my defenses. I was brought up to believe this person is my enemy, and when he spoke to me in Afrikaans, I felt guilty and started crying. I felt responsible, that my people and I were brought up to believe that he is the enemy. And yet you can see the sincerity on his face, his smile; and [I was thinking] why was I so afraid of him. It was in complete contrast to what I expected and I cried. He told me at that first meeting I was overreacting.

Did you draw any criticism in the early years when working for him?

At first, there was a lot of criticism within his own political circles, about why he chose a white woman. He was very careful to relate that story to me at first, knowing I was sensitive and after a while, he would joke about it. He would repeat the entire conversation and say: “Can you believe they would say this?”

It also provided people with entertainment. Madiba’s and my sense of humor had a strange similarity; so we would joke about even these things. He was always looking for humor in any situation. There is nothing laughable about being in prison for 27 years, but he was always trying to find the lighter side of things.

Did he ever get angry?

He had vices and virtues like everyone else. He was a very determined, almost hotheaded person. You couldn’t sway him once he decided something. You knew not to mess with him when he was angry. [But] Madiba didn’t hold grudges, he would get over something very quickly but you would know exactly how he felt. If you look at the CODESA negotiations, he was really angry at F.W. de Klerk at some point – the photographers managed to capture his body language beautifully. He managed to change the narrative. He always had this mindset of reconciliation, of unity, and there was a strategy behind whatever he did.

How was the transition once he retired from the Presidency?

The morning after his retirement was quite a wakeup call. We thought we would pretty much have access to state resources, and we could rely on certain things from the government, but any retiring head of state is in for a full surprise. We had no media protocol, no foreign affairs – all of that was gone.

You have traveled widely with him. Any memories?

I am reminded of our visit to Iran, during President Khatami’s presidency. In the book, you will see how important women’s empowerment is for Madiba. He insisted on me going to the palace where women are not allowed. So we went to dinner at the President’s residence, and there were only male bodyguards and security. I was fighting off photographers, as Madiba’s eyes were sensitive to flashlights. I tried staying in the back so not to offend anybody with my presence. It was very noticeable I was the only female there. A butler then sent for me, and Madiba said, “Oh Zeldina, the President wants to have supper with you.” The whole time, the President asked about South Africa, and Madiba would not answer; so I had to speak. I was put on the spot.

Did you get to spend enough time with him in the final years?

The later years, from 2008, when he started slowing down, he stopped all public appearances and meetings. There was no business any longer to discuss. I tried to go once a week to Qunu [to meet him], more on a personal basis.

How did you come to terms with his passing?

Those ten days of the funeral, I will never want to relive again. You have to deal with the outpouring of emotions from the outside world, and you don’t have time to deal with your own emotions. I still find myself thinking, has it really happened, is he really not there anymore? I have never lost anyone close to me. I am very fortunate. Both my parents are still alive. This is a very new experience for me.

Are you still in touch with

Graça Machel?

I am very close to her. She is true to her name; she epitomizes grace and strength and has been an emotional stronghold for all of us, through his illness. She was not there only for Madiba, but for us as well.

What kind of work are you

involved in now?

I am still contracted with the Nelson Mandela Foundation; at present [I take part in] leadership courses for the foundation, and I do a bit of motivational speaking, just telling people my story and conveying the lessons I have learnt.

Did you ever think you put your life on hold?

I think I have gained so much, and have been so exceptionally privileged that I wouldn’t say I put my life on hold really. It evolved into something greater. My working hours were nonstop. When Madiba was President, he would call at 2AM and say, can you get hold of Minister Trevor Manuel? I didn’t go for a movie for 10 years. I was too scared he would call and I wouldn’t be able to help him.

You were very special to him?

It would be incorrect to say I was the only one, or the special one. There were other people who played vital roles in his life. My role was confined to his public life, so people need to see it in the context of my duties.