Former South African president Nelson Mandela, in his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom, puts it best when he says,

“I have walked that long road to freedom. I have tried not to falter; I have made missteps along the way. But I have discovered the secret that after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb.

“I have taken a moment here to rest, to steal a view of the glorious vista that surrounds me, to look back on the distance I have come.

“But I can only rest for a moment, for with freedom come responsibilities, and I dare not linger, for my long walk is not ended.”

These words resonate when assessing just how far women have come since the advent of democracy in South Africa, almost 20 years ago. And more importantly, how much more still needs to be done to realize gender equality and the fundamental transformation for women.

Looking back, there is no denying that change, even if it is slow and patchy in some areas, has impacted for the better, on the lived realities of women in Africa’s largest and most diverse economy.

Today, women are sitting at the head of the table in politics, business, the judiciary and almost all aspects of society. South Africa’s Constitution and Bill of Rights wiped off the statute books several laws which sought to make African women in general and black women in particular the appendages of their husbands, brothers and fathers.

It also restored to women their cultural rights, and ensured that these rights are protected by law. This provides some respite from the negative implications of some aspects of various cultures, which often see women pulling the short end of the stick.

South Africa has provided women leaders to Africa in the form of Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, who is now the chairperson of the African Union Commission. South African women also serve the globe, with the appointment of former deputy president Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka as the head of UN Women. These are just two examples of quality leadership developed and home-brewed in South Africa.

The economic rights in the country’s Constitution, at least on paper, also give legal recourse and protection to the indigent and marginalized. And given that poverty, disease and inequality remain feminized, this inclusion of second-generation rights is of particular significance for women.

While head-counting alone in the political arena is not always a true yardstick by which to measure gender equality, it does reflect critical mass, and marks just how important the visibility of women in leadership positions ought to be.

In the South African Cabinet, women are well represented, holding key ministries such as transport, defense, agriculture, home affairs and international relations. Of the nine provinces, five are led by women premiers, and the country’s massive police service is headed by Riah Phiyega.

One of the newest political parties to contest the 2014 general elections, Agang, is headed by Dr. Mamphela Ramphele, a medical doctor and acade-

mic, who at the age of 65 has decided to run for political office.

Looking at the economic baro-meter, the picture is not as rosy, but it does show some slow progress. The 2012 Women in Leadership Census is a report conducted by the Business Women’s Association. Based on a survey of JSE-listed companies, state-owned enterprises and government, it shows that women in private enterprises occupied 4% of CEO or MD positions, 6% of board chair positions, 17% of directorships and 21% of exe-cutive management positions.

The report also found that women in executive management positions were more likely to be white than black, but that women holding directorships were more likely to be black.

Women are also lagging behind in the judiciary. South Africa’s justice minister, Jeff Radebe, says women continue to be under-represented as judges in the country’s court system, with only about a quarter in permanent posts.

He has also pointed out that of the 233 permanent judges appointed to different superior courts in the country, only 65 are women. Of that number, 45 are black and 20 are white.

This under-representation is not limited to judicial appointments. The allocation of legal work and briefs to legal practitioners is another area where there is almost a complete absence of women.

But change is afoot, according to Radebe, who plans to radically overhaul the criminal justice system to ensure gender parity and greater equality for women.

During Apartheid, however, women had to fight to make change happen.

On August 9, 1956, 20,000 South African women embarked on a march to demand the scrapping of the hated Pass laws. Marching in their thousands, their war cry rang out clearly: “Wathint’ abafazi, Strijdom! Wathint imbokodo uzo Kufa! (Now you have touched the women, Strijdom! You have struck a rock! You have dislodged a boulder! You will be crushed!)”

Even then, women made it clear that they would defy any efforts to prescribe their place in society. Even then, when repression was at its peak, women were determined to bring about change that would eventually see them participate as equals in the drafting of the country’s covenant, regarded as among the most progressive in the world.

This is why South Africans celebrate not only International Women’s Day on March 8, but also National Women’s Day on August 9. And as a mark of just how important gender equality is, the entire month of August is commemorated as Women’s Month. It not only allows for celebrating the gains made, but is also an opportunity to reflect on the drawbacks, the impediments and what more ought to and should be done to deepen gender equality.

Former South African deputy president, Baleka Mbete, who also serves on the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), remembers the key role women played in negotiating the new dispensation. She says that even in the ruling African National Congress (ANC), women still had to battle to have their voices heard.

“Even in the ANC, it wasn’t smooth sailing. The key was to be visible. Activism was at the root of what women were about. We had to do a lot of convincing to impact on the process. What we realized was that we needed to work together as women.”

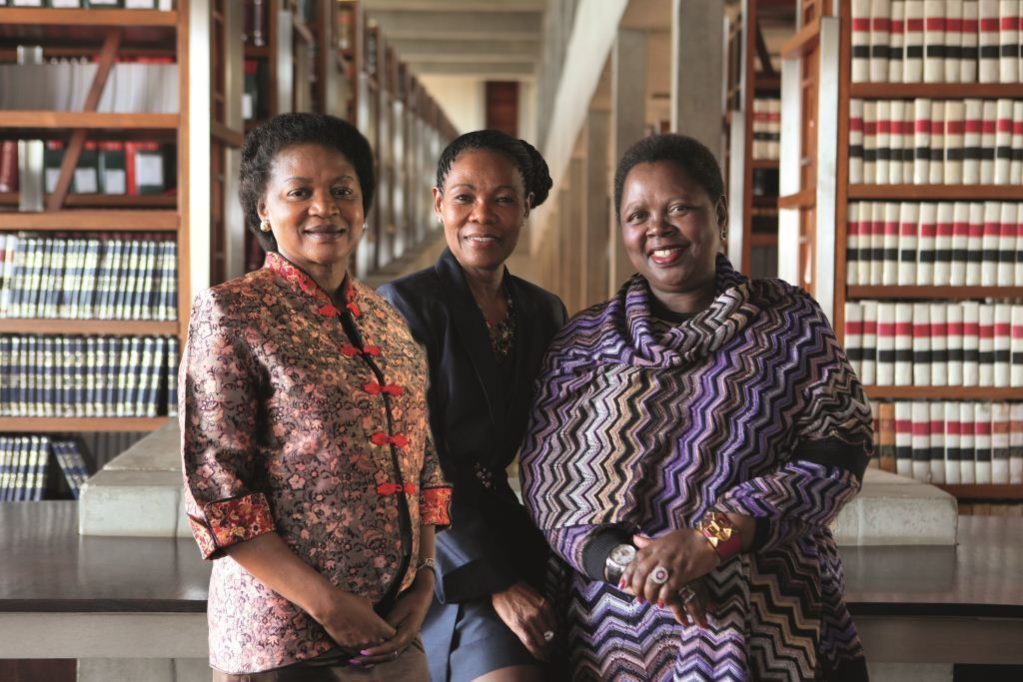

Former Constitutional Court Judge Yvonne Mokgoro says the Constitution and the Bill of Rights are the two single most important documents that have changed women’s lives in South Africa.

“Poverty, as you know, is feminized, so too is indignity. For me, our Constitution and Bill of Rights are of particular relevance to women.

“Our Constitution is a covenant between us as a people. We didn’t sit in dark corners when it was drawn up. We – and I include us as women – negotiated that Constitution.

“What we need to do when we give life to what is contained in our Constitution is to dig deeper, do more. Set up monitoring mechanisms to ensure proper delivery of those services for people, but also for women in particular,” she says.

While the political struggle has seen great dividends, change in South Africa’s boardrooms is slow and often resisted. Back in 1994, Gloria Serobe, together with Wendy Luhabe, Louisa Mojela and Nomhle Canca, started a company called Wiphold, specifically to grow women’s investments. They believed that political emancipation without economic gains in the boardroom would constitute a pyrrhic victory for women.

Serobe, an accomplished and savvy businesswoman, who is wise in the ways of the world of commerce and high finance, says she and her co-founders realized that “true economic empowerment would require a process of wealth mobilization and accumulation, and that this would be especially important in the case of women’s empowerment”. She says this led them to explore the use of women’s investment clubs as ‘empowerment vehicles’.

Using workshops and educational forums, they crisscrossed the country, ratcheting up support from women across various socio-economic groups. The founders, after raising seed capital of $50,000 formed the WIP Four Company, Wiphold in microcosm. The company listed in the Investment Trust sector on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange five years later.

“Wiphold is the first organization dedicated explicitly to women’s economic empowerment to achieve a JSE listing. All board members are women. Voting control rests with the Wiphold Investment Trust. In early 2000, value created for the Trust stood at $6.85 million,” Serobe says.

Wiphold later delisted from the JSE, but Serobe points out that of all the empowerment companies formed back in the 1990s, Wiphold is “still standing”.

Mbete and Mokgoro concur that South Africa in 2013 is a much better place for women in politics, business, government and in the social sphere. They are also united in the belief that the journey which started 56 years ago, when those courageous women marched against the Apartheid system, has to continue. Especially if women in South Africa are to achieve a real and qualitative shift – not only on paper, but also in behavior and attitude towards greater freedom, equality and gender parity.