The drone market is on a growth trajectory. In rural Africa, they are being increasingly used for transporting life-saving drugs and for collecting data for geographic information systems, agriculture and even film-making.

DUMISANI KALIATI’S UNIVERSITY was close to a hospital, and each time he would walk past it, he would meet women asking for money. He would later find out why – they were patients coming from far, from districts outside Blantyre, in Malawi, and needing transport to their homes in the rural parts.

He says deeper in the communities, there are no demarcated roads, in places, only foot paths exist through thick forests or up the mountains.

This led him to ask: how can he help people living in remote areas, remotely?

He first developed an SMS-based app to remind patients to take their medication.

“But that was not enough. I was still looking for ways to reach out to those in the rural areas with physical medication. And around 2016, I got news that Malawi was introducing a drone corridor in 2017, and I started to research how local startups or individuals like myself could benefit from the drone corridor,” says Kaliati, the founder of MicroMek, a Malawian hardware startup developing low- cost Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) for remote medicine delivery.

This year, MicroMek was contracted by UNICEF to survey the damage done by tropical storm Ana.

Kalaiti says having only one main road up the escarpment in Blantyre creates challenges when there are disruptions in weather, and the arterial M1 road was destroyed in three places by the flooding. His drone helped.

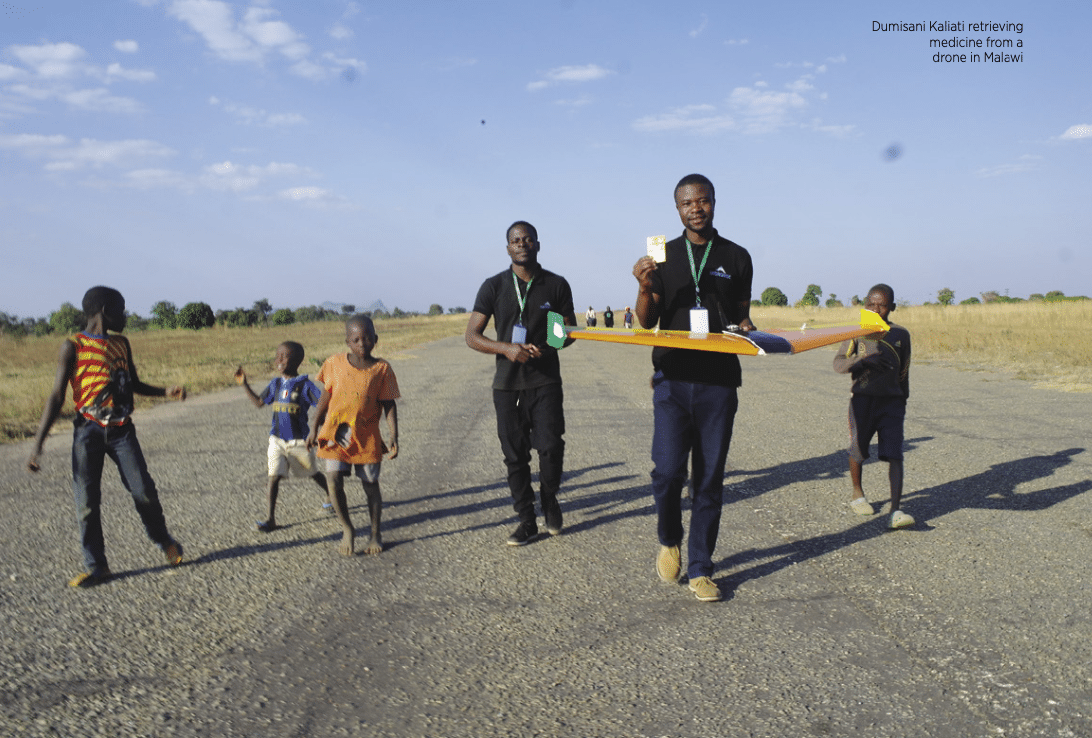

Kaliati founded MicroMek in his third year of university studying science and information technology. MicroMek builds drones from 3D-printed parts and recycled material in Malawi, working with the Virginia Tech University’s Unmanned Systems Lab. EcoSoar is a simple fabrication designed to deliver medicine, dried blood samples, vaccines and other critical medicines in the UNICEF Kasungu drone corridor in Malawi to the Kasungu district hospital. An important aspect is the time reduction in the delivery of diagnostics, vaccines and medicines.

His drones are also being used for environmental sensing. Since 2018, he has conducted over 1,000 test flights with medicinal supplies and for aerial data collection.

MicroMek is in its pilot phase, with 65 women participating, also doing community surveys about the challenges they face and the medication the people in far-flung areas need.

So far, they have tested with family planning medication, and pregnancy and HIV test kits. Kaliati says communities have widely welcomed the service.

“I think there is a big opportunity, mainly if we look at current economic trends, while at the same time at the Covid-19 pandemic, when we were in total lockdown; things like drones are autonomous and minimize human contact… all these are opportunities that are defining the new normal, the new way of doing things, and the next industry,” he says.

MicroMek also trains young local people as drone pilots, enabling cost-reductions in operations.

“At the same time, when you’re looking at costs on the medical side of things, it’s tricky to put a cost on saving lives. For example, if a person is in need of blood and you are able to carry 500ml of blood within an hour, and it’s the only package you’re carrying, it becomes hard to put a price on it. It’s life- saving,” Kaliati says.

The EcoSoar fixed-wing drones can go up to 30km for aerial mapping, while the tail seater vertical take-off and landing UAVs can carry up to 1kg for medical deliveries, he says. The first costs $350 while the second costs approximately $430 to manufacture. They finalized production on the tail seater in February. MicroMek is developing the drones to go further, to multiple facilities, carrying up to 6kg of weight.

The growth of the Remotely Piloted Aircraft (RPA) industry in 2019 was predicted to be worth $43 billion by 2024, a compound growth rate of 20.5%. Currently, the drone market is worth $26.3

billion. The Drone Market Report 2021-2026 from German analytics firm Drone Industry Insights (DII), reports reaching $41.3 billion by 2026, a 9.4% compound annual growth.

The slower growth outlook is being attributed to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. India is set to see a growth of 20.6%, outstripping other continents’ progress, while the South American market is set to see a promising compound growth rate of 11.3%. Despite the conservative global growth estimates, the report by DII says if UAV companies capitalize on the increased investments and positive attention to drone technology, then the industry could profit from a K-shaped recovery, growing faster than the data suggests. Uneven economic recovery is a possibility, especially in a post-pandemic world: different sectors demand needs be met, perhaps with alternatives.

South Africa’s drone market is also on a growth trajectory, estimated to reach $134.5 million by 2025, according to a report by IndustryARC. The research found the expansion is due to the growth in the mining industry, developments in more data- accurate drone technology and the presence of dominant players in hardware and niche applications.

“What we’re seeing is that the increase in global investment has resulted in an increased number of drone applications and density of drones within an airspace. For example, Australia has about a million drones in operation, with estimates that 8% of the population now own a drone,” says Greg Dillon, Lead of Sport, Events, Entertainment & Drones at specialist insurer iTOO, in a press statement.

Diverse uses and leapfrogging opportunities

The current gaps in road transport infrastructure in East Africa and sub-Saharan Africa are vast, amounting to billions of dollars annually, according to a World Bank (WB) report, ‘Unlocking the Lower Skies’, in 2021. UAVs are being used in multiple industries; for collecting data for geographic information systems, agriculture, healthcare and film-making. Their applications include inspection, mapping, filming and drone delivery to spray and seed farmlands. RPAs are even being used to monitor wildfires.

Rwanda first used UAVs for medical services to deliver blood supplies in partnership with US startup Zipline. While drones were more expensive than the motorcycles and cars that distributed blood supplies to rural areas, money was saved due to speed – it takes 13 to

26 minutes to get blood to outlying areas compared to hours – and blood wastage has dropped from 38% to 3%. Moreover, there were fewer deaths as communities have faster access to blood. The country’s Minister of ICT and Innovation Paula Ingabire said the above at a World Economic Forum event in 2019 and that the investment had ripple effects; a burgeoning of startups with drones also being used to spray pesticides in Rwanda to combat Malaria.

In March this year, Zipline announced a deal with Ghana’s Ministry of Health to scale to four additional distribution centers covering 24 million people — bringing Zipline’s coverage to 90% of the country’s population. The company also aided in Ghana’s Covid-19 vaccine distribution efforts, delivering nearly one million Covid-19 vaccines, with plans to distribute more.

In Rwanda, Zipline has expanded into 24/7 operations and now delivers critical supplies around the clock. The company has now announced expansions into Nigeria, the Ivory Coast and Kenya.

Overall, Zipline surpassed 275,000 commercial deliveries and currently makes a delivery every four minutes on average.

“New technologies are transforming transportation, and electric autonomous drones epitomize the immediate leapfrogging opportunity for emerging markets,” says Hafez M.H. Ghanem, Vice President, Eastern and Southern Africa Region of the World Bank, in a 2021 report.

Overall, the research by Stokenberga and Ochoa in the Ukerewe district in Tanzania revealed that high quantities of products result in relatively low costs per flight. Significantly more flights, and UAVs required to deliver the same quantities that ground transport carry out, mean the net result is higher costs. Small volumes (such as in the case of life-saving items) and infrequent demand mean few flights with high costs per flight, says the WB report in 2021.

Importantly, the WB report says layering use cases can be efficient and cost-saving, by allocating fixed costs across a greater number of flights and maximizing drone capacity as well as time use. The base case absorbs fixed costs and startup capital costs. Additional layered use cases incur incremental operations costs.

Ramping up the number of flights per UAV reduces overall per-flight costs, and combining products per flight maximizes capacity usage of the vehicle.

With routine deliveries, cost-effectiveness can be amplified by using ‘milk runs’ (going to multiple facilities in one flight) rather than hub-and-spoke routes. Excess capacity is used by including cargo for multiple facilities, therefore total mileage reduced.

Opportunities for UAV transport cost reduction lie in layering life- saving items; rabies vaccine deliveries, laboratory samples, and blood deliveries making up the base cases.

However, given the estimated time needed to complete one trip; preparation, packing, unpacking and flying, a single UAV can be expected to achieve 1,200-1,600 flights per year.

Much of the challenges surrounding the scaling of drones has been economically motivated, with a partiality towards ground transport. ‘The Lancet’ medical journal compared distribution programs using motorcycles and UAVs during the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, finding that the longer the range (100km), the more cost-effective drones became.

South Africa, Rwanda, Kenya, Ghana, and Tanzania have now also issued or updated comprehensive regulatory guidelines on the use of UAVs for sports, private undertakings and commercial applications within their airspace.

On the other hand, the governments of Morocco, Algeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and Madagascar have decided to prohibit the use of UAVs by the general public and utilize them for their own security services.

Currently, regulation in South Africa has been overtaken by the technology of drones to an extent, with regulators reporting that stricter UAV laws to counter the likelihood of accidents and incidents are required.

Use of RPAs

RPAs can be a replacement for light planes, offering a cheaper monitoring system, potentially staying aloft longer. An area UAVs could be crucial is for countries facing challenges in acquiring and maintaining light aircraft, or where there is a dearth of runways in remote areas, says Matt Herbert, Research Manager at the North Africa and Sahel Observatory, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. Furthermore, helicopters and light aircraft have more fixed and continuous costs.

“I think there’s the potential to use it for search and rescue, because these are relatively cheaper to purchase and maintain than light aircraft and the pilots that go with them, I think there’s the potential to get more of them and employ them at more of an increased tempo,” says Herbert.

He adds that while speculative, the potential is certainly there. If drones could be used for helping victims of disasters, helping aid get to people quicker, that is where there could be a positive impact in how governments engage their citizenry, he explains.

“As you’ve seen with mobile finance coming out of Kenya, coming out of Nigeria – in many ways, the lack of development in some sectors enables a much more unconstrained thinking in innovation about the potential opportunities and trajectories of different technologies. So, texting cash would not have been something that would’ve been easily identified and scaled within for example, Europe, but M-Pesa, it took off,” says Herbert.

“Certainly the tech talent exists within Africa: the potential for thinking about how to create drones that are able to do different things under different environments. And there’s also the demand, there’s potentially the need. We’ve already started to see indications of some domestic current manufacture,” he says.

Drones offer a benefit in delivery, despite existing rapid transportation such as roads, and because the continent is so big, there’s opportunity for UAVs to be scaled in the coming years, concludes Herbert.