The U.S. government has disclosed more of its case against WikiLeaks cofounder Julian Assange. It hinges on a claim he and Chelsea Manning worked together to crack a password for a computer storing sensitive government files.

An affidavit unsealed Monday outlining the case against Assange said he conspired with Manning when they discussed working together to crack a password “related to two computers with access to classified national security information.” More specifically, the password belonged to a user called FTP (not to be confused with an FTP server) on two Windows computers that Manning could access from a base in Iraq, the government said.

The FTP account wasn’t associated with any specific individual, and the government alleged that if Manning had used it to pilfer files and hand them over to Wikileaks, she could have foiled investigators looking into who was behind the leaks.

“Although there is no evidence that the password to the FTP user was obtained, had Manning done so, she would have been able to take steps to procure classified information under a username that did not belong to her,” the affidavit read. “Such measures would have frustrated attempts to identify the source of the disclosures to WikiLeaks.”

The alleged conspiracy to crack the password took place in March 2010, two months after she’d walked out of the Iraq base with classified war reports from Iraq and Afghanistan. She was later convicted and served seven years in jail for downloading tens of thousands U.S. military documents and diplomatic cables.

How passwords are cracked

The reason any password had to be cracked in the first place was the use of what’s known as a “hash.” Microsoft’s Windows operating system doesn’t store passwords in plain text. That’s to prevent hackers who find a way on to the computer from seeing and stealing them. Instead, Microsoft makes life harder for cybercriminals and snoops by turning that plain text into scrambled code. That string of letters and numbers is known as a “hash value” and it’s created when an algorithm is applied to the plain text of the password.

For an attacker to get at the plain text it’s possible to do a so-called “brute force attack.” The process for this is basic: The hacker creates a huge list of guessed passwords through the same hashing algorithm used by Windows to find a matched hash value for the hidden password. Once the same hash value is calculated, the password has been found.

Sometimes a password will be too complex for guessing to work in a short enough time frame. That’s where “rainbow tables” come in. These contain a massive number of hash values for previously calculated passwords. Hackers use them to do a quick comparison of the hash they have with the ones in the table, in the hopes that it’s already been seen before and a match is available.

“In computing terms we call this a time/memory trade-off. Rather than spend time on a task, we pre-calculate parts of it and store them somewhere, essentially trading time for memory,” says Tom Wyatt, senior penetration tester at cybersecurity provider Bulletproof. “These tables can be calculated or downloaded from various online sources, and it simply boils down to paying for storage for it all; even in 2010 this was fairly cheap and entirely possible.”

But Microsoft goes one step further in protecting those hash values by splitting them in two, storing the parts in separate files. Here’s where a little trick comes in handy: A hacker might be able to recover those two separate pieces by rebooting a Windows PC using a CD with the Linux operating system. Back in 2010, it was possible to do that and recover the full hash value.

Ken Munro, a penetration tester with Pen Test Partners, told Forbes the technique still works, as long as there’s no additional layer of security over it, such as full disc encryption. “Whilst the technique still works, it’s quite rare to find systems that don’t now have full disc or similar encryption,” he added. (Microsoft hadn’t responded to a request for comment at the time of publication). According to the government’s telling of the story, evidence suggests Manning tried, and very possibly failed, with this technique. In a footnote in the affidavit, the government said Manning hadn’t provided Assange with the full hash, only one of the two halves required.

It’s alleged Manning passed what she thought was a hash value to Assange. The Wikileaks chief then said he would pass it on to a specialist in cracking, according to chats over the Jabber encrypted communications app, as provided in the affidavit. But, as per the investigators’ claims, there was some confusion: Manning said she wasn’t even sure what she handed to Assange was the hash value they wanted. Assange messaged Manning to ask if there were “any more hints” about the hash and that he’d had “no luck so far,” according to the government account. From there it’s unclear what happened. The government admits it didn’t know whether the password was ever cracked.

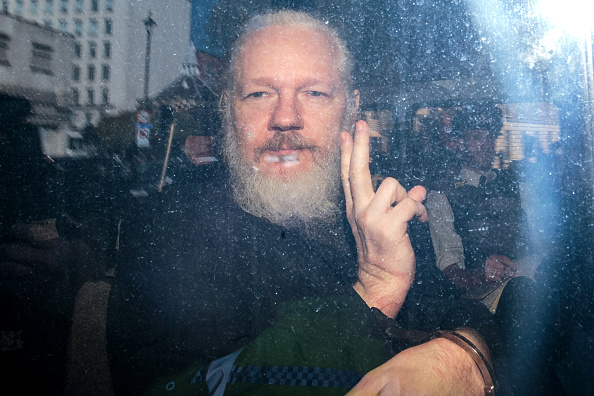

Not that it changes much for Assange: The charge is that of conspiracy. If he did offer assistance to help Manning gain access to U.S. government systems and encouraged the then intelligence analyst to leak files, the charge still stands. Manning, who served seven years in jail before being pardoned by President Barack Obama, is back behind bars for refusing to testify in the investigation into Wikileaks. Her lawyer had not responded to a request for comment at the time of publication.

Assange’s lawyer, Jennifer Robinson, couldn’t be reached for comment at the time of publication. She told Sky News yesterday that the indictment against her client showed “the kinds of communications journalists have with sources all the time.” Following Assange’s arrest, however, various journalists have said on Twitter that any incitement to hack organizations or steal documents was far from normal and risked breaking the law.

Meanwhile, the fallout from Assange’s arrest continues. According to Reuters, Ecuador’s telecommunications vice minister Patricio Real said the government’s networks had been hit by a mass of cyberattacks after it decided to revoke Assange’s asylum status. He claimed various government websites had been slammed by 40 million hacking attempts per day, double the number it typically sees.

-Thomas Brewster; Forbes Staff