This was the bizarre tour of a lifetime, arranged by world football legend Sir Stanley Matthews for youngsters he had trained in Soweto in defiance of apartheid laws.

“At the airport I was riddled with nerves but tried to overcome them by busying myself shepherding my young charges and allaying their obvious fears. Large, forbidding men in light blue suits and dark glasses with inscrutable looks on their faces watched our every move but, uncomfortable as it was, they never approached us. At any given second I expected us to be rounded up, hustled into vans and taken away to one of South Africa’s infamous police stations but it never happened,” wrote Stanley in his autobiography.

“I couldn’t believe it and neither could Stan’s Men. We were on our way out of the country bound for Brazil, the first ever black football team to tour outside of South Africa.”

Yet, apartheid followed the youngsters to Rio de Janeiro, in the shape of an intelligence man who sat at the back of the plane.

This strange journey was the work of one of the greatest English players ever. Matthews was the first European Footballer of the Year in 1956, who played top flight football until he was 50. They called him the ‘Wizard of the Dribble’ and he was loved the world over.

For the love of the game Matthews came to South Africa and defied the country’s segregation law to turn township talent into stars. This story is to be told this year in a United States documentary, called Matthews.

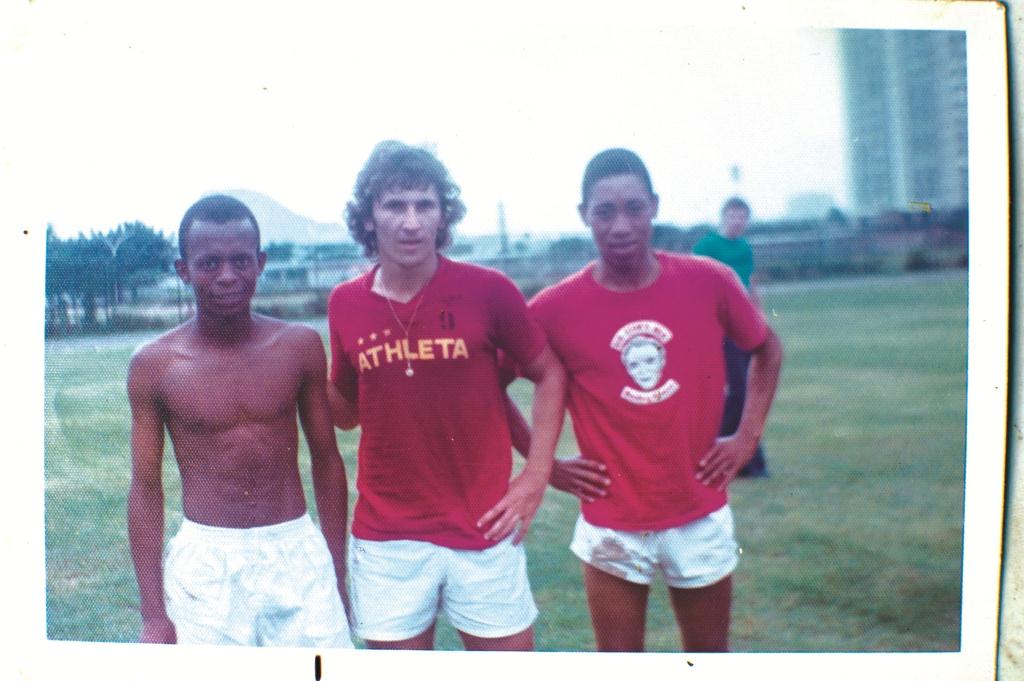

In the summer of 1975, Matthews spent months scouting talent from schools in Soweto, Johannesburg’s biggest township, and formed a team called Stan’s Men which he took on tour to Brazil. It was born of a question from a youngster on whether Matthews had ever played against Pelé. This led to an unheard of trip from South Africa. Matthews used his influence to get sponsors in the shape of Coca Cola and the Sunday Times, as well as passports for the boys, against the norms of the time.

“Sir Stan was a brave man, it was unlawful for white people to be in townships at that time but he was in Orlando every week to train us. He would come to our home to meet with our parents. Initially the parents thought we were crazy when we told them about going to Brazil but because Sir Stan was known to them they soon believed we were telling the truth,” says Hamilton Majola, then aged 17.

“During those days, Orlando Stadium was our mecca of football. For the Brazil tour, it was not easy, we trained hard. There were hundreds of talented footballers from all over Soweto but only 15 could be selected. Dedication and discipline were key to Sir Stan,” says Isaac Masigo, another youngster who boarded the plane for Brazil.

March 21, 1975, was the first day of the month-long tour to Brazil. It had taken weeks of hard training that created a good deal of excitement.

“On that Friday, learning in Soweto schools was disrupted… learners were running mad, so many children were bussed to Jan Smuts (OR Tambo International Airport) for our send-off… I will never forget that day, it was surreal,” says Masigo.

On the Boeing 707, destined for Brazil, the lads were anxious and smart. They dressed neatly in tailored navy suits with a gold badge, with Stan’s Men printed on it, blue shirts, navy ties, with red and white dots, and shiny black shoes. Upon arrival in Brazil, they were treated like stars and journalists flocked around them. They felt like stars staying at the Hotel Regina, in Rio, on the famous Copacabana Beach. Most had never seen the sea.

They went to practise with Flamengo Football Club and met Arthur Antunes Coimbra, better known as Zico, who was to star in the World Cup for Brazil. This was one of the players they had only seen on the bioscope, a makeshift cinema back home; televisions didn’t come to South Africa until a year later.

“Carlos Alberto Pereira, who coached Bafana Bafana in the 2010 World Cup, I met him in 1975. We played and took pictures with Brazilian stars. We trained with big teams like Flamengo, Fluminense, Vasco da Gama and Americana. The culture there was different from what we know in South Africa. The clubs there had coaches for different departments, kit manager, physiotherapist and that was not the case in Johannesburg. We trained from 6AM to noon. There they start training you from childhood, in South Africa we are playing games,” says Masigo.

The first game in Rio was a huge disappointment. The youngsters played alongside their coach Matthews, then aged 60, the first game against Gama Filho University and were drubbed 8-0.

“That was embarrassing; their ball was different from ours. Our dribbling skills couldn’t get us anywhere. They man marked so tight that we couldn’t manage a single goal. Brazilians meant business; our goalkeeper left the field with swollen hands. He cried. If it was not for Sir Stan things could have been worse,” says Majola.

One of the spectators was the white South African intelligence officer who tracked their every move.

“We were followed but we couldn’t see. The security police followed us from the airport to Brazil, they couldn’t trust black boys… One day, on our way to the hotel, a white Afrikaner man shocked us: ‘Ja (yes), you blacks of South Africa, you stay nice here’,” says Masigo.

Although the boys didn’t do anything to warrant jail back home; they broke the rules of Matthews when he wasn’t looking.

“After the training, when Sir Stan was resting, we were free to go the clubs and beach. There was this Copacabana Beach, the best beach in the world. It was women galore, I sweated as if I was running under the sun,” says Masigo.

The Brazilian women in swimwear mistook the African boys, kitted out in red-and-white tracksuits, for Americans, laughs Masigo.

Majola knows Matthews, a teetotaller and vegetarian, did not approve of these outings.

“Sir Stan taught us life values; from the beginning he said we mustn’t go for girls because they would destroy our football future. He warned us against alcohol,” says Majola.

Soon after Brazil, Matthews returned to England but he left a foundation in Soweto. The team continued playing friendly games, outside the country, in Swaziland and Botswana.

“When we returned from Brazil, the Sunday Times, which was one of our sponsors, reported on our tour and one of the headlines read ‘They are now internationals’. There was so much jealousy from other local teams as a result we were not allowed to affiliate to the local leagues. We played friendlies. Things started to get unfriendly. We can’t be pointing fingers now, maybe it was God’s will. The fact Sir Stan left his country and family to share his football skills with us, we had nothing to offer him in return,” says Majola.

“I had seen and experienced what football could do for an individual and I wanted others to realize not only the possibilities that football can bring, but to get in touch with the possibilities that lay within themselves, irrespective of how hard and demeaning their lives were. If I could enjoy such benefit from football, I was determined to show others such benefits existed for them as well,” wrote Matthews.

“It would have been easy for Sir Stan to start a commanding club with us but he was threatened against doing that. Every big company wanted to sponsor our team. We were treated well, we had sponsored transport to all our matches,” says Masigo.

The team dissolved and many went to other clubs. One, Vincent Tsie, Masigo’s only schoolmate on the Brazil trip, found the country’s laws unbearable after the Brazil trip and took off.

“After he saw the life in Brazil he refused to stay in the racist South Africa anymore. In 1976, he went to exile in Canada where he died,” says Masigo.

“I was also tempted to leave but I couldn’t do it because I was the eldest of my siblings and couldn’t leave them. I knew what happened to Kalamazoo (Steve Mokone, the first black South African in the European league who died in exile).” Masigo, now a pensioner, still lives in Orlando.

At 50, Matthews played his last professional game for Stoke City, the town of his birth. He died on February 23, 2002, aged 85. In February, Matthews would have been 101 years old.

His contribution to African football is timeless and will never be forgotten in Soweto.