A few weeks before Floyd Mayweather swaggered into the ring in Las Vegas, a forgotten centenary slipped by that lends context to the struggle of the black man.

On April 5, 1915, the first ever black heavyweight champion of the world lost his title after 26 brutal rounds at a racetrack in Havana, Cuba. It was the end of a remarkable story of pride, skill and refusal to back down in the face of cruel and repulsive racism. Each of his stirring fights was punctuated by a torrent of vile abuse – mostly in the United States, the self-proclaimed land of the free – that would have made a neo-Nazi blush.

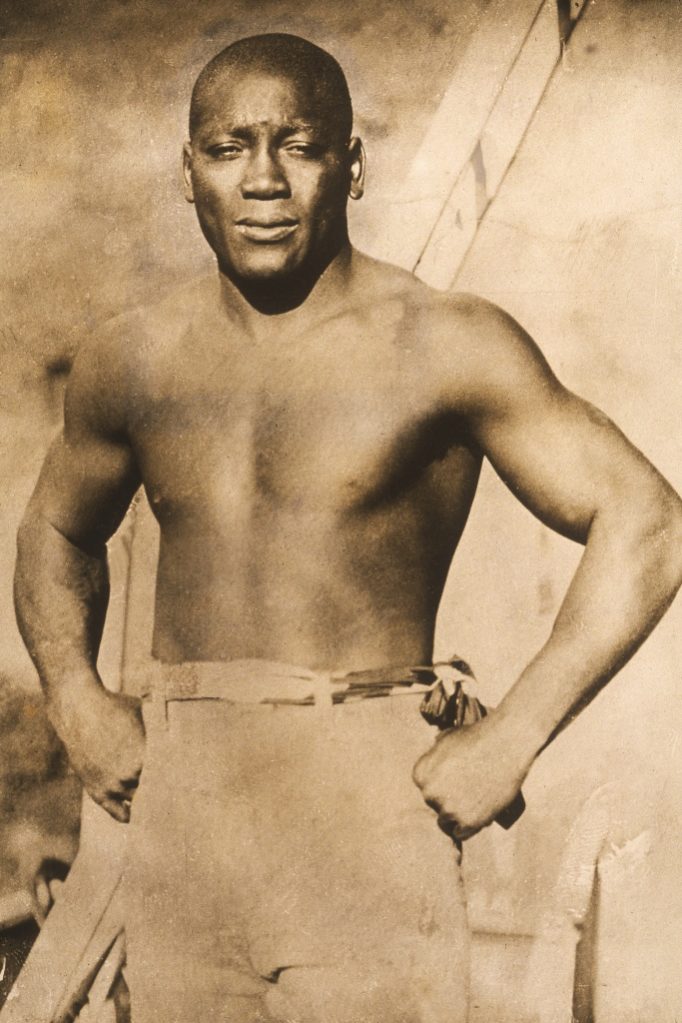

They called Jack Johnson, the son of a slave from Texas, the Galveston Giant, for he was every inch so. He was over six foot, with a broad chest that looked chiselled out of mahogany; he bowed for no man and boxed into his 60s. Out of the ring, Johnson was a flamboyant man about town who smoked huge cigars, drank champagne, dressed in the finest suits and drove expensive cars at a time when most of the world was walking.

In the ring, Johnson was a supreme mover and technical genius that few could lay a glove on. He started each fight with beguiling ease, as if he was kidding his opponent to death, in the words of his biographer Geoffrey C. Ward in his book Unforgivable Blackness. As the rounds went by the punching power would grow steadily, with lurking devastating uppercuts that threatened to rip off a boxer’s head.

This was how Johnson won his world title in Sydney, Australia, the day after Christmas in 1908. The fact there was an unofficial color bar in boxing makes the title win ever more remarkable. For two years, Johnson haunted the corner of the heavyweight title holder Canadian Tommy Burns. As corner men towelled Burns down, after another victory, Johnson shouted from ringside that Burns was no champion until he had fought him. Yes, these things happened before Don King was even thought of.

Money twisted the arm of Burns, who said many times he would never fight a black man. Greed and money had always ruled boxing.

Round after round, in Sydney, Burns, who had power but little sense, insulted Johnson’s race and called him a coward as he charged. Johnson smiled and taunted back.

“Poor little Tommy, who told you you were a fighter?” joked Johnson.

“This is what is known as a left hook, Tommy,” before stepping and letting fly with a bone-shuddering left.

In the 14th round, as Johnson hammered Burns to the floor, there came press censorship. Legend has it that the police ordered the camera to stop filming during the knockout. Certainly, the edited footage cuts out the moment when Burns hit the canvas; it was deemed unseemly to show a black man victorious over a white.

Despite this, Johnson landed a resounding blow for the black man in Sydney. Sadly, in the United States (US), angry lynch mobs murdered more than 20 innocent black men, in racial retribution.

Johnson defended his title eight times in six and a half years. The tirade against him grew as the newspapers made a meal of his lavish lifestyle and relationships with white women. The man himself, one of the greatest boxers ever to lace up a pair of gloves, didn’t give a damn.

The great man’s reign also gave rise to the phrase: the ‘great white hope’ for any boxer attempting to wrest the title back from black hands. One of them, former heavyweight champion James J Jeffries, came out of retirement on US Independence Day, July 4, 1910. Trains carried thousands to the fight, in Reno, Nevada, that could have doubled as a Nuremburg rally. Guns weren’t allowed because the organizers thought someone was going to shoot Johnson. The crowd satisfied itself by firing racist insults throughout.

Johnson had the last laugh, pummelling Jeffries to the floor, earning $121,000, in modern money a sum near the amount for the Mayweather fight. He drove to pick up the money, in cash, from a nearby diner on the way home.

The end came in Havana just over 100 years ago. A hard right hand from Jess Willard, the Pottawatomie Giant, in the 26th round knocked Johnson to the canvas. Age, heat and exhaustion had caught up; there were whispers Johnson had thrown the fight for money. Maybe, maybe not?

Either way, Johnson never wore the crown again and his life ended on a sad note of bathos; the Galveston Giant died, aged 67, when his car hit a telegraph pole. He had driven away angrily from a North Carolina diner after yet more discrimination against the color of his skin.

The centenary is maybe time to pause and think. One hundred years on, from Johnson to Mayweather, the world of boxing may have cleaned up its act, but has the world?