It was a Friday afternoon, June 4 2010, just a few days before one of the biggest days in African history. Flags were on the streets and the mood was festive in the countdown to the 2010 World Cup—the first time the greatest tournament on earth had kicked off on Africa’s red soil.

Mandla Sibeko strolled, in a mellow mood, towards Green Point Stadium in Cape Town, happy in the knowledge that by the opening ceremony on June 11 his job would be done—the end of years of struggle with the rigorous rules of the soccer governing body, FIFA. An angry phone call shattered this mellow mood and ushered in Sibeko’s worst day.

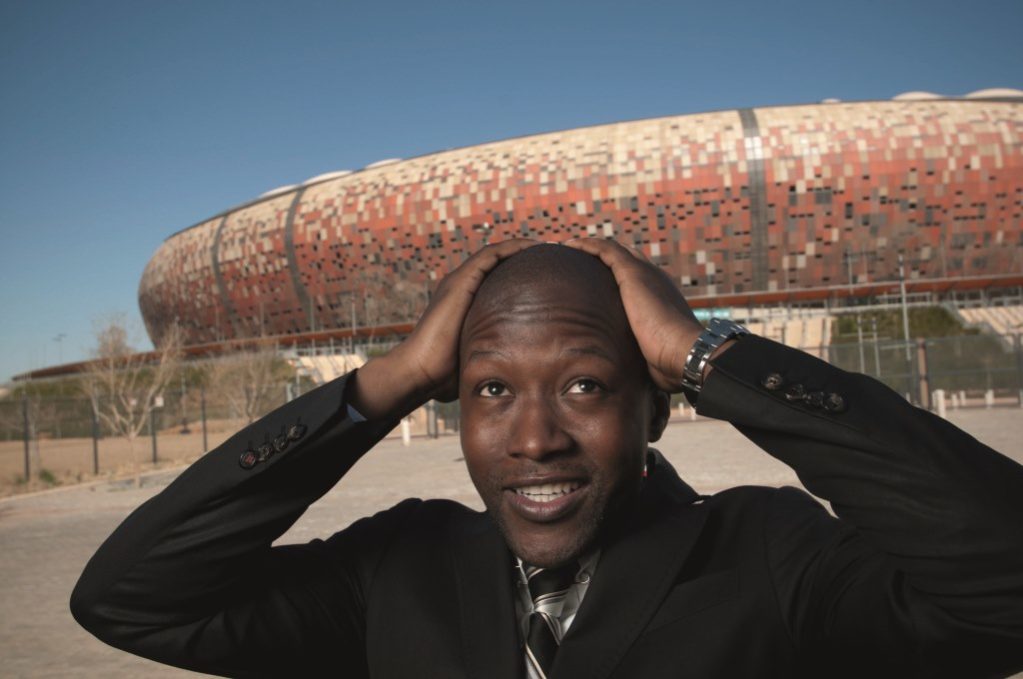

Mandla Sibeko thinking about his worst day

Sibeko was used to struggle. He was born in Johannesburg, the youngest of six children, and grew up in poverty near Nelspruit in South Africa’s north-eastern Mpumalanga province; his first school lesson was held under a tree in the village of Kwaggafontein and the floors of the classrooms were made of cow dung, for want of concrete.

“Whenever I smell cattle dung, I think of those early school days,” says Sibeko.

Luckily for Sibeko, his mother was a domestic worker for a wealthy white family in Johannesburg and they offered to pay for his education.

“They have moved to Australia and I sent them an email the other day saying that decision changed my life. They wrote back to say they were proud to do so. It is amazing how one decision can change your life,” says Sibeko with a smile.

From the age of eight, Sibeko went to the elite St Martin’s School in Johannesburg, followed by a degree in law at Wits University. By the age of 24 he had set up his own business, making TV programs for the SABC. In 2007, he became the first person to open a Pick n Pay supermarket—once a preserve of the suburbs—in Soweto.

“In all these businesses I fell and got up many times. Soweto business is the hardest money you will ever earn, the customers are so demanding. I was working from 5am to midnight every day. We wanted to prove you could do business in the townships and we doubled our turnover in the first year.”

Sibeko became a shareholder in Identity and Tone Digital signage companies and then, while still in his late 20s, came the offer of a key job in the staging of the first ever World Cup in Africa. In 2008, British company Icon, which had helped to stage three World Cups, made Sibeko the CEO, along with a 40% stake, of their South African subsidiary. The job was to oversee the signage for the entire tournament. It was a huge job and Sibeko also saw it as a way to strike a blow for Africa.

“In my work I wanted to tackle this Afro pessimism—we dealt with people who doubted us. People were asking us: “do you really know what you are doing?”

The job entailed making sure all was correct on the flags, buses, hotels, signposts and banners at the country’s 10 World Cup stadiums.

“It was painful because you have to think for people. Everyone has an opinion, the Local Organizing Committee has an opinion, FIFA has an opinion; no one is right or wrong. Signage alone is a problem. Sometimes it arrives and is the wrong size and you have to send it back to Bloemfontien on a truck. Print quality can be poor, colors wrong and the position of the logo can be wrong. FIFA is very fussy—it’s their way or no way. They want it to be done better than the last World Cup.”

So Sibeko oversaw a rigorous system of checks. There was a long list of checks before the signs got to the printers; at the printers there was another check; then the signs were checked again before they were loaded onto trucks and yet again at their destination.

All this counted for nothing at 2pm on June 4 2010 when a top FIFA official screamed down the phone at Sibeko, just hours before an inspection team was due to tour Green Point Stadium.

“She was furious. There was no kindness about it, it was: ‘you guys have messed it up!’

The terrible truth was the misspelt word: “Welcme” hanging over the main entrance to the stadium. It wasn’t a welcoming sight for Sibeko.

“I don’t know what happened. It was 20 to 30 meters tall. This was a huge mistake. The A team of the World Cup was coming to inspect and what we had promised was not ready. We freaked out. I felt cold. We all expected this day. This was our do or die moment, we had worked for nearly four years and now we were going to mess it up because of a missing ‘o’.”

The crisis could have been costly. From this moment on, in the balance was a multimillion-dollar contract. Sibeko had to act fast.

“I called all the stadiums to check out if they had the same problem. It was difficult to find people quickly. At that point I was very anxious, I wanted to know whether we had made more mistakes along the way. I started to think about whether flags were facing the right way up when Sepp Blatter drives past. I froze, I didn’t know what to do. I am normally a very calm person, but on that day my staff said they had never seen me like that.”

The next step was to call a printer in Cape Town to make a new sign. It wasn’t easy as many World Cup service providers had lots of work, so it was easy for them to say no. Otherwise, Sibeko would have had to rope in a Johannesburg printer to get a new bulky banner flown down to Cape Town. For the first time in the day, lady luck smiled on Sibeko and a Cape Town printer agreed.

Then there was the problem of getting the huge banner up at the stadium before the inspectors arrived on the following day. It was already dark when the truck pulled up with the banner. So, by poor light, a team of 10 workers scaled ladders.

“They had problems because it was dark. They started at 8pm and

finished at midnight. We had another 10 people on the ground from my company and many of them were ready to walk because they were overstretched and felt they were not appreciated. Not everyone felt the importance of the biggest sporting event in the world. I said to them that I understood they were all under pressure. I talked about patriotism; this was their country, I told them, they had to keep going because they were doing this for their country. Maybe Mandela would have been proud of me!”

Crisis averted, thanks to elbow grease and a friendly Cape Town printer, but for Sibeko, his worst day put a damper on the greatest show on earth.

“That was the end of my torture, but then it became a difficult process because you had let down the client in the closing stages. When everyone was celebrating we were suffering. The opening I didn’t enjoy because I was wondering what else is going to go wrong. As much as the nation was celebrating, I was suffering, I was just wondering when it was all going to come to an end!”

Sibeko went to Brazil earlier this year to see how the country was preparing for the next World Cup.

“I just thought South Africans undervalue themselves. Brazil is so well marketed and yet it doesn’t deliver as much as South Africa does. I have to say we are too hard on ourselves. Stadiums are not going up at all and secondly, there was no sign of commitment from people, there was just a lot of talk. It will be interesting to see how fast they get up to speed.”

Mandla Sibeko offers his World Cup experience to the Brazilians. He hopes, by contrast to 2010, his experience will be as beautiful as the game itself. That would be welcme; sorry, welcome!