Acentury ago, the Governor of the Hunan province famously began a censorship trend in China, that later reached its nadir under Mao Zedong’s cultural revolution, when he banned Lewis Carrol’s allegedly subversive literary waltz around the garden: Alice In Wonderland.

A few years ago, I found myself on the ragged borders of Hunan on an investigative trail that had taken me from rural Malawi to an obscure corner of China where 100 billion counterfeit cigarettes are mass-produced, literally underground, each year.

As I arrived to dig for tobacco, China’s pre-occupation with censorship continued to focus on the surreal in the present not just the past. Afraid that the so-called Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia would inspire similar insurgence in Beijing, the Chinese Communist Party had, as I drove across Hunan, declared an unlikely war on the small white flower, even banning its utterance from social media.

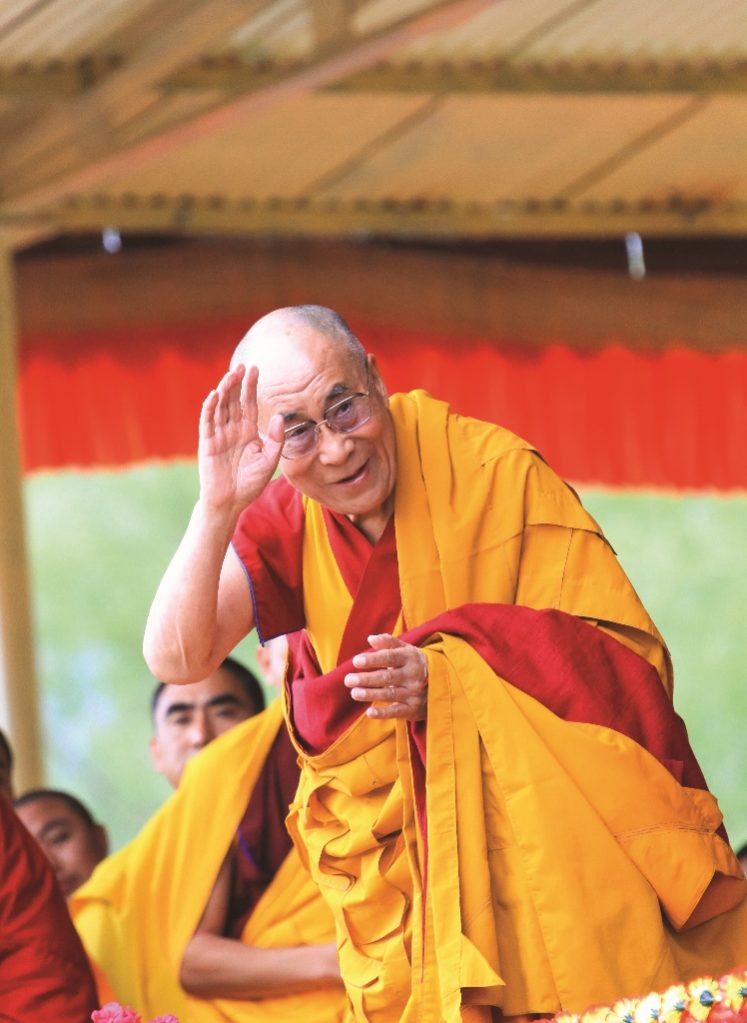

China likes to outlaw symbols of resistance. It regularly bans people too. Richard Gere and Brad Pitt, not exactly the most threatening of civil rights campaigners, will be unlikely to ever walk along the Great Wall of China thanks to their personal association with a humble Buddhist monk who has become the world’s most high profile blacklistee: the Dalai Lama.

The latest storm of controversy swirls around the South African government’s refusal to grant the Dalai Lama a visa to attend the World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates in Cape Town in mid-October.

In 2014, as they have for much of the last 50 years, Beijing views Buddhism’s Yellow Hat as a meddlesome separatist trying to establish an independent Tibet. But he’s also a very effective tool that China uses to incrementally assert control in international affairs.

As far as Pretoria is concerned, we are in familiar territory. In 2009, Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader tried unsuccessfully to visit South Africa to attend a peace conference. Before then he had visited the country three times under Presidents Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki.

Two years later, in 2011, the Dalai Lama hoped to attend the 80th birthday celebration of his friend, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, but withdrew his request after not receiving a response from Pretoria. An angry archbishop later described his government’s handling of the visa application as mind-blowing.

A year later, South Africa’s Supreme Court of Appeal found that the country’s home minister at the time unreasonably delayed her decision on the Dalai Lama’s visa application and acted unlawfully in doing so.

Of course it is beyond dispute that the Rainbow Nation’s most recent point-blank refusal to grant entry to one of the world’s holiest figures has more to do with Beijing than Pretoria.

The furore around the rejection promoted the Dalai Lama’s fellow peace laureates, including Poland’s Lech Walesa, Bangladeshi entrepreneur Muhammad Yunus, Iranian lawyer Shirin Ebadi, Liberian activist Leymah Gbowee and Northern Irish peacemakers David Trimble and John Hume, to write a letter directly to President Jacob Zuma calling for a reversal of the decision. When the reversal didn’t come, the laureates cancelled their trip to South Africa.

What is most surprising to me is the low-key reaction to the latest rebuke in Asia. It speaks of a wider truth. Since China’s emergence as an economic superpower, the Dalai Lama is increasingly becoming the last person presidents and prime ministers would ever want to ‘Like’ on Facebook. As a consequence South Africa is far from the only nation in the world to ‘unfriend’ the 14th incarnation of the Buddhist holy seat.

Around the world, governments are increasingly limiting their contact with the Dalai Lama’s office. Most recently, Russia refused him entry. Those who refuse to kow-tow often feel the muscle of China. After the British Prime Minister David Cameron met with the Dalai Lama in 2013, after Beijing warned him not to, China effectively cut off diplomatic relations. Cameron’s administration then spent a year working to get back in Beijing’s good books.

A more startling row over the Dalai Lama’s presence took place in the last place you would expect. Norway. A nation that has shaped a reputation for tolerance. When the Dalai Lama visited Norway in May, government officials allowed him to enter the country but refused to meet him face to face. Norway had previously found itself in the cold and its salmon exports to China decimated after it had chosen the Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo as the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize recipient. History wasn’t about to repeat itself.

In the midst of the latest scandal, South Africa’s foreign ministry has, of course, stressed its visa decisions were taken independently of a desire to cultivate closer ties with China, its largest trading partner and co-member of the BRICS club of emerging economies.

Regardless, the country’s economic relationship with China deepens. In late 2007, China made the largest single foreign investment in South Africa since the end of apartheid, a deal for the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the biggest lending bank in Asia, to take a 20% stake in South Africa’s Standard Bank, the country’s largest by assets. Last year, China emerged as South Africa’s foremost trading partner.

The deeper truth to the Dalai Lama’s exile and predicament can be found between the lines of academic study. According to a study by two European scholars, Andreas Fuchs and Nils-Hendrik Klann, inviting the Buddhist leader for dinner could ultimately end up costing you the earth.

In their study ‘Paying a Visit: The Dalai Lama Effect on International Trade’, they found that when a top leader meets with the Dalai Lama, that country’s exports to China will drop by at least 8.1% for roughly two years, and then return to normal – in the interim costing economies linked to China billions of dollars.

Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that in 2001, the Dalai Lama met with 11 top leaders yet in 2013 met with only two. This trend of avoiding the Tibetan spiritual leader has been especially pronounced in northern Europe, not just in Africa.

But a greater reality in the modern world is the Dalai Lama’s political influence, like the strength of his tenure, spent entirely in exile, is fading fast. A man of compromise and dignity, he has long said he’d settle for autonomy within the Chinese state, but this has about as much chance of happening as China recognising Korea’s right to re-unification. Today, as China’s economy grows, Tibet’s state-supporters will continue to diminish.

Tibet has changed dramatically in recent years. On the political front, tension is still very much present but the wave of self-immolations that once dominated world headlines has diminished. Even the soldiers who were blocking most of the streets of old-Lhasa in 2008 are now gone.

Money seems to be having an impact on Tibet for better or worse. After having invested $15 billion on infrastructure in 20 years, and committing further $15 billion in the years to come, China has equipped Tibet with a reliable road network, five airports and a railway line anchoring it firmly to the nation. Greenhouse agriculture is developing, allowing a constant outflow of highly prized fruit and vegetables throughout the year. This year, 12 million, mostly Chinese, tourists made the trip, turning Lhasa into a tourist hotspot.

This, in itself, sadly lends a rather hollow ring to the words of the Dalai Lama himself: “Money and power facilitate, but it is clear that they are not the primary causes of happiness and solving the world’s problems.”