The early twentieth-century South African educationist and writer, Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu, was no stranger to irony. Responding to news of the outbreak of the First World War, he commented wryly in September, 1914 that Africans had been ‘taken by surprise that the European nations who led in education and Christianity should find no other means than accumulated destructive weapons to settle their diplomatic differences’.

Like many others at that chilling moment, this pacifist viewed the war as a distant European catastrophe. As we reach the centenary of the cataclysmic Great War of 1914-1918, images of the Western Front and of the conflict as a bloody European affair continue to dominate popular historical memory, and not solely in Western countries.

Further back in time, significant figures grasped that it was a dramatic global struggle, far-reaching in its destructive and transforming impact on Europe’s enormous imperial territories overseas and their hundreds of millions of colonial inhabitants. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was just one of those observers. With Britain the major colonial power in Africa, for Churchill it followed that British Africa would be at war with Germany, just as night followed day. Italian leader Benito Mussolini observed that every continent was engulfed by the same crisis and not a single part of the world had been able to avoid being shaken by what he called the cyclone of 1914 to 1918.

In that sense, the war experiences of imperial Britain, imperial France and imperial Germany were as much about the fortunes of Africa as about the fate of men in the trenches of Europe. Aside from anything else, even those soldiers were by no means all European. In all, the French recruited almost 400,000 West African and North African colonial troops to fight German invaders. Many others who were pulled into Europe kept their heads down, serving the war effort as military laborers. Even crops exported from its African territories helped keep France on its feet. Africans thus became an inseparable part of the war.

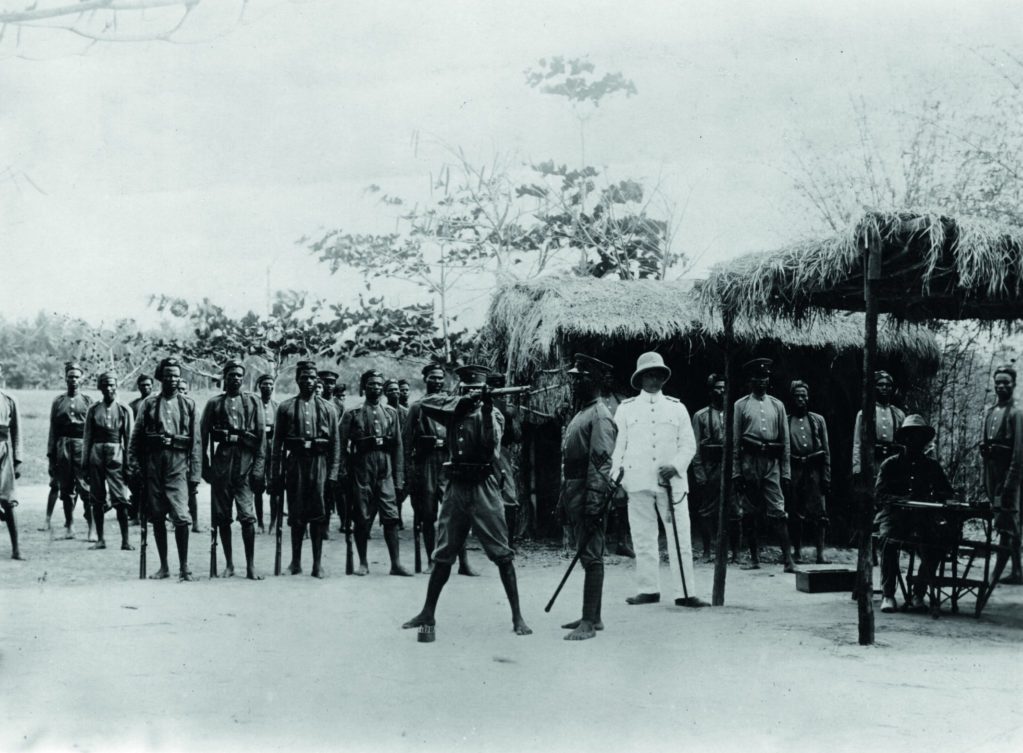

Another perspective points us towards Africa itself. After all, it was there that the war actually started. The very first shots were fired by West African infantrymen of Britain’s Gold Coast Regiment early in August, 1914 when British and French colonial forces invaded Germany’s colonies of Togoland and Kamerun. That extinguished the delusions of some local colonial administrators that Africa might have been left to remain neutral. What they feared was the unsettling effect of European hostilities on the security of white rule.

Africa was also where the war finally ended. It was still simmering on the continent after it had ended in Europe. In the week following Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, East African askari – guerrilla fighters under German command – picked off a British motorcyclist in Northern Rhodesia. Among his scattered papers was a notice that the war had ended. It came as a rude surprise to the German commander, General Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck. Now obliged to surrender, he did so grudgingly, moaning that he was only giving up because his country had been defeated in Europe.

Some of the war’s quirkier stories were as good as any fiction, if not better. In the Union of South Africa’s conquest of German South West Africa in 1915, they included General Louis Botha’s decision to swop his horse for a motorcar for his triumphal entry into the enemy capital of Windhoek. With an eye on awaiting war correspondents, he had been keen to shed his rural Boer commando past in favor of appearing as a modern industrial soldier. Unfortunately for the prime minister’s dignity, his driver had possibly had one brandy too many on the way to victory and drove into a ditch. A year later, the obsessively fit and healthy Jan Smuts, commander-in-chief of the large Allied campaign in East Africa, was not exactly popular among his more idle and chubby generals. At the sound of their commander’s approaching Buick car, officers ducked out of their tents and tried to hide away, desperate to avoid having to accompany him on some strenuous mountain walk.

Meanwhile, lower down in the ranks, ordinary soldiers and army laborers enduring arduous tropical bush conditions faced another kind of daily menace. On top of malaria, typhoid, dysentery and other parasitic diseases which toppled many thousands, there was the aggravation of wandering elephants, giraffe and rhino getting in the way, the threat of venomous snakes around tents and the danger of hungry lions and leopards prowling near campsites.

Of course, the real human costs of the war in Africa were not inflicted by wild animals. Forming a grim undercurrent, these losses were immense. On one hand, it is true that Allied campaigns to deprive Germany of its West African and South West African ports and wireless facilities by conquering its colonial territories involved little effort and minimal loss. Pretoria, for instance, gained control of a huge south western territory at a cost of a little more than 100 troops.

On the other hand, German East Africa was a nut that could not be cracked as easily. There, in an unrelentingly ferocious and destructive contest which oozed across from East Africa into Central Africa and down into South Eastern Africa, opposing forces engaged in a long and gruelling see-saw struggle. The wholesale plundering of peasant lands and mass conscription of villagers that it brought imposed a terrible toll. With horses and other draught animals laid low by tsetse fly and trucks unable to cope with the poor terrain, both sides resorted to conscripting men to work as transport porters and carriers. Britain alone recruited at least a million laborers. Overworked, malnourished and exposed to appalling conditions, up to 200,000 died. At the same time, around 300,000 inhabitants of German-occupied areas perished from the effects of famine as their livestock and crops were looted by soldiers. The suffering didn’t end there. Late in 1918, the deadly worldwide Spanish influenza struck hard, spreading throughout the continent to infect populations already weakened by the war.

By then, the region had not only been feeling the burden of a war that was embraced by many white colonists but which was otherwise resented by the vast majority of their black subjects. It was also adapting to its momentous consequences. In what has sometimes been termed the second partition of Africa, Germany was eliminated from the continent. To the victors, including South Africa, went the spoils. Jan Smuts was now able to advance his vision of the new Union of 1910 becoming a Greater South Africa. As for Britain, by securing control of German East Africa as Tanganyika, it was finally able to realize Cecil Rhodes’s bombastic vision of an all-red road from the Cape to Cairo. Until African decolonization and independence decades later, the First World War settled which powers would keep what.

Still, looking back from where we are now, we can also see that the end of hostilities did not mean a simple return to business as usual. Following the Paris Peace Conference and the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, control of the conquered colonies was mandated by the newly-created League of Nations. Although limited in practice, for the first time this introduced the principle of international humanitarian trusteeship into colonial Africa. In effect, those states which had gained new territories were their guardians and could not do entirely as they wished with them.

In post-war decades both Britain and France found themselves having to commit new educational, medical, administrative and commercial resources to the development of their African possessions to beef up the legitimacy of their colonial rule. After the blood and chaos of the war, colonial rule needed to provide Africans with security, stability and progress.

Inevitably, the glimpse of mighty European powers on the ropes left a deep mark on the consciousness of returning African war veterans. The hollowness of Europe’s claims upon superior civilization and enlightenment had been laid bare. There was widespread disillusion that Africans’ wartime sacrifices and contributions had gone virtually unrecognized and unrewarded.

Black South African papers like Abantu Batho applauded United States President Woodrow Wilson’s declaration of national rights and freedom from oppression. If that was being prescribed for European nations after 1918, should there not also be recognition of the justice of African claims? Less than a century ago, it was still too early.