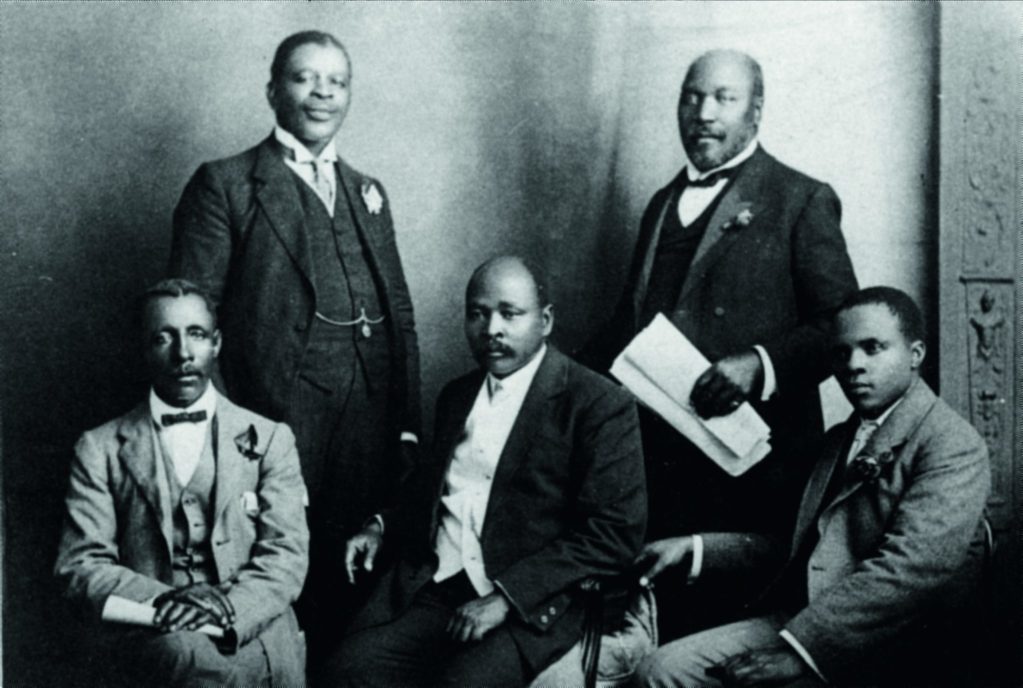

On June 14, 1914, Sol Plaatje and four young educated African men, clad in British-styled suits and snazzy bow ties, boarded passenger ship, Aberdeen Liner, in Cape Town’s harbor.

The five men were on their way to argue with the British government for the repeal of the Natives’ Land Act of 1913, which had effectively taken away their rights to own land. This was the first shot in the land battle that lingers in South Africa to this day.

“They were pioneers of the black struggle who correctly identified the root cause of the African’s plight and misery. Overnight a native man found himself not a slave but a pariah in his own land,” says Pan Africanist Congress president Letlapha Mphahlele.

The University of Witwatersrand’s history professor Philip Bonner describes Plaatje as a relatively conservative but militant leader who dedicated his life to the freedom of his people.

The harsh provisions of this act appalled Plaatje and sent him on a lifelong mission. He wrote about it in his newspaper column and gave speeches to the African People’s Organisation, of which he was a member.

On the other side, the British government was at the height of its power. The empire held sway over one quarter of the world with territories on every continent.

The African delegation to England was from the South African Native National Congress (SANNC). The team consisted of KwaZulu-Natal born Rev. John Dube, who was the founding president and Oberlin College gradute, in the United States (US); Rev. Walter Rubusana, a Xhosa leader who accompanied the AbaThembu king Sabata Dalindyebo to the coronation of King Edward VII in 1904; Thomas Maphikela, of which little is known; Saul Msane, who had toured Europe with a Zulu choir in 1892 and worked as a compound manager for a gold mine before he was caught up in politics; and Plaatje, an author and journalist.

“I went on the deck to catch the last glimpse of the African shore, with the hilly district to the east, off what used to be Hottentot’s Holland. The majestic Table Mountain was receding in the distance and Cape Town, which had always represented the end of the world to me… was out of sight,” Plaatje wrote in his diary.

En route, Plaatje also wrote a book on the Natives’ Land Act which he hoped to publish on arrival in England.

The Anti-Slavery and Aborigines’ Protection Society, a humanitarian organization for colonial affairs, met the group when they landed in London. It warned them not to agitate the issue until they had met with Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Harcourt.

The meeting was a flop. The British said they would not interfere in the affairs of a colony. The five disappointed travelers from South Africa resolved to take their case to the British people. They printed pamphlets and organized meetings. But in a couple of weeks, differences emerged between them and the campaign petered out.

Plaatje stayed on and took a language assistant job at London University. He finished writing the three books that he started on the voyage, including a book railing against the act—Native Life in South Africa.

Plaatje threw himself into a one-man campaign; in two years he addressed roughly 300 meetings in England. On the way he acquired an enemy, John Harris, the organizing secretary of the Anti-Slavery and Aboriginals Society.

Perplexingly, Harris was a supporter of the racial segregation embodied in the act and he used his position to turn people against Plaatje.

In February 1917, Plaatje left England. Less than two years later, the SANCC sent him back with another team, this time to meet the prime minister, David Lloyd George.

Lloyd George told Plaatje and his colleagues they had a powerful case and they had caused him distress.

However, the second rendezvous with the British Empire again yielded nothing. This stalemate sent Plaatje and his one man campaign to the United States and Canada.

In the States, Plaatje shared a platform with Marcus Garvey, the leader of Universal Negro Improvement Association, and the Back to Africa movement.

Plaatje returned home late in 1923 to intensify his lobby but found South Africa’s political landscape even more racially divided.

Plaatje spent the rest of his life as a journalist, human rights campaigner, novelist, translator and linguist. He was the first black person to have kept a war diary; he chronicled the Siege of Mafikeng in the Anglo-Boer War. He also translated Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors into Setswana. He died on June 19, 1932 from pneumonia while traveling to Johannesburg from his home in Bloemfontein.

Today it would take Plaatje a mere 10 hours to reach London from O.R. Tambo International Airport in Johannesburg, rather than a month by ship, but the land question has changed little.

Nearly 20 years into a democratic South Africa, rural development and land reform Minister Gugile Nkwinti says a mere eight million hectares of land has been handed over, a long way from the targeted 24.6 million. This has cost the government $2.8 billion (R30 billion) and it is estimated that another $2.8 million is needed to finish the program.

A mere 5,000 of the 76,000 claimants took up the land; the rest opted for cash.

Mphahlele says it is a tragedy that people opted for money as many slip back into poverty. He also criticized the willing–buyer, willing-seller policy.

“You have 100 willing buyers, yet there is not a single seller. The whole scheme is easily manipulated by the market forces, they are asking for 20 times the value of the land.”

Agri-South Africa, an agricultural trade association, disagrees.

“As far as Agri-SA is concerned willing-buyer, willing-seller did not fail. We do not think it was the main problem in the implementation of land distribution. We believe the government failed to implement it fully,” says the association’s legal and policy adviser, Annelize Crosby.

“Market value was one of the factors that had to be taken into account when determining a purchase price for land intended for land reform. The government, however, says it intends on moving away from market value as a basis for compensation. The Restitution on Land Commission Rights has conducted poor research with regard to land valuation which has resulted in a very weak implementation of the land restitution.”

Mphahlele, however, counters that claim.

“Land restitution in South Africa, to me, was never meant to remedy the deprivation of African land but act as a painkiller. A painkiller doesn’t heal anything… African farmers are not getting enough support from the government, unlike white farmers who were subsidized by their white minority government,” he says.

“The long delays in land ownership transfers stems from price disputes between sellers and the government, and willing–seller, willing-buyer is the main factor for it. The revised strategy of paying a landowner a just and equitable price for their land will help speed things up,” says African Farmers Association of South Africa deputy president Mandla Buthelezi.

“The accusations that landowners are inflating their prices are impossible. Land valuers are appointed by the government; land owners cannot influence the price. The price can be negotiated with the land owner but he cannot dictate terms to the government,” argues Theo de Jager, Agri-SA deputy president and registered property valuer.

With debate as passionate and pertinent as that which followed the Natives’ Land Act exactly 100 years ago; you can be sure if Plaatje and company were around today, they would be taking the Gautrain to O.R. Tambo Airport.