A lesser-known consequence of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, is the separation of African families, whose members found themselves on the wrong side of the border, just as intensive lockdown measures and border closures were imposed. We speak to two families who, while grappling with the uncertainties of the virus, are now wondering when they’ll be able to meet again.

In March, after nearly a year of battling a tough job market, Corrie wa Mutu was thrilled to begin a consultancy with an environmental NGO in rural Tanzania. Having worked on a number of development projects around the continent, the American-born agro-forestry expert relocated to Nairobi, with her husband and two young children, in 2014 from Maryland. Now 45-years-old, she claims that being based in the region, at last, was the realization of a dream, nurtured since she was a girl.

Mutu was just settling into her role when news of the first confirmed case of Covid-19 in East Africa broke. She didn’t realize it then, but her life would soon be shaken by it.

“I left Nairobi on March 2, my husband and the kids kept to their daily routines when President Kenyatta announced the first case [in Kenya]. Of course, I had planned to visit the family in Nairobi a few times during my consultancy since I would have never considered staying away for months at a time with young children,” she recalls.

It’s been over two months and Mutu has not yet returned to her children. Shortly after that announcement, a series of intensive lockdown measures were introduced, the most recent a travel ban prohibiting unauthorized movement in to, and out of, the country’s capital, where her family resides.

Kenyans wishing to return to the country must complete a compulsory two-week quarantine, at the border, before receiving official clearance to travel on to their respective towns or villages. For Mutu and her family, seeing each other again, even for a short time, meant enduring a number of bureaucratic hurdles.

“I needed to stay on as long as possible to complete as much work as I could before going back due to my family’s financial situation. If I decided to go back to visit my family, I would have to go through the minimum 14-days at the Kenyan border, find a way to exit Nairobi after my visit, and then, when I crossed back into Tanzania, I would be put in quarantine for another 14 days, at the minimum,” she explains.

Mutu was caught between a rock and a hard place. She could either brave the prospect of at least 28 days in quarantine, in order to see her family for a few days, or stay put in Tanzania, away from her young children, until her contract concluded. Inevitably, she had to choose the latter.

“Spending time in quarantine facilities in two different countries, [with] no idea what the sanitation and testing conditions would be, and not being entirely sure that I would [be able to] exit Nairobi once I got back in, meant [that] that scenario was untenable,” she continues.

Hard as that decision might have been for Mutu, it could have been for the best. In late April, reports began emerging about the conditions at Kenya’s quarantine centers. Many returned to the country, hoping to see their families sooner rather than later, but instead found themselves marooned, with little clarity on when they would be allowed to leave.

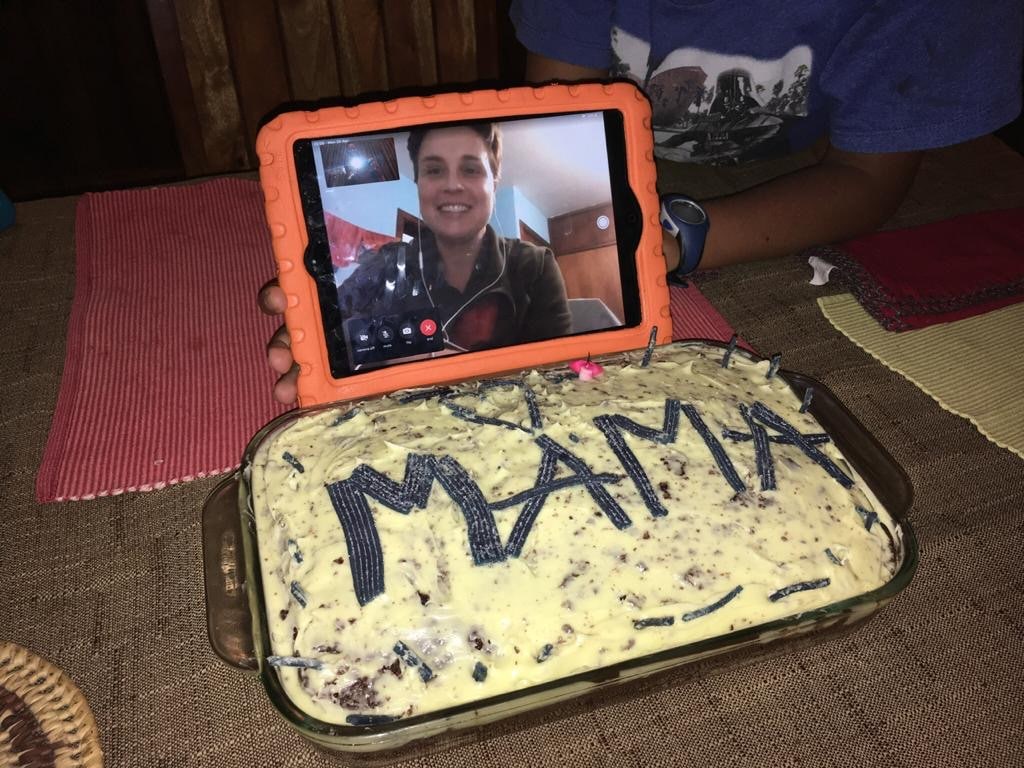

Across the border, in Tanzania, technology has had to step in so Mutu can maintain essential contact with her family. She does her best to speak to her children, who are 11 and eight years old, almost daily, checking in on whether their homework and chores are done. The family also continues to keep their weekly tradition of Bible study going every weekend. Despite the distance, the kids also managed a surprise on her birthday.

“My birthday was on the 18th of April, so the kids made me a cake. They even asked what flavors I wanted! We had a video call while they sang and blew out the candles for me. Then they got to eat it on my behalf, and I can tell you it was one of the sweetest birthday moments that I’ve ever had!”

A continent away, another African family is also making the best of the situation after being separated by the pandemic. Gifty Quainoo-Appiah, a Ghanaian entrepreneur living in London, found herself an ocean apart from her husband, who was in New York City, on business, when borders closed.

The family had been together for several months and planned to see each other again, a few weeks later, once their one-year-old daughter had her immunization records updated in the United Kingdom. They have been separated since February.

“Our relationship is based on travel. I have a business in Ghana, however, my husband, who is also Ghanaian, has business in the States, and I am based in the UK. We mostly travel back and forth between these three countries. It’s just so unfortunate that Covid-19 has come about and [it] hasn’t given us much choice in the matter. We split [briefly] and now we’re stuck in our designated countries,” she says.

The United States quickly overtook Italy’s grim record of Covid-19 fatalities, in mid-April, with New York City declared a virus epicenter soon after. Undoubtedly, the Quainoo-Appiahs have had to consider what this might mean for them but, on the whole, they remain optimistic.

“It’s unfortunate that [where my husband is] has been hardest hit and borders have been closed. I really worry about him even having to step out [of his apartment] because of this, even if he’s just going to the supermarket. It’s really difficult with such a young child and this happening so early in our marriage. We had so much to look forward to and, now, everything seems beyond our control. You can’t make any decision outside of a video call or a text message and that’s now the basis of our relationship.”

In addition to these pressures, being apart has meant that Quainoo-Appiah’s husband has had to miss some important milestones in his daughter’s life, which every parent hopes to witness and immortalize.

“He’s missed our daughter’s first steps, her first words. He even, unfortunately, missed her first birthday! So much has happened during this time that he hasn’t been there for but we are thankful for our good health,” she says.

The business in Ghana is also a concern. Around the world, countless businesses have been claimed by the pandemic. Ongoing trade and travel restrictions coupled with a decline in consumer spending have also left Quainoo-Appiah’s business vulnerable.

“The business in Ghana is unmanned. We’re fortunate enough to have my father-in-law to help manage things while we’re away. My business is in online [fashion] retail and, of course, traffic has reduced but this means I’ve had to think of marketing strategies that are out-of-the-box. We even did a campaign advertising loungewear and comfy clothes to stay indoors. It could be a lot worse, I just need to keep my customers engaged for now,’ she says.

Back in East Africa, Mutu is also helping her organization, and clients, adapt to the new climate of the virus.

“The tree-planting organization I am working with took precautions since the first confirmed case was announced [in March], especially during our seedling distribution period. All staff wear masks and keep recommended distance. Our beneficiaries enter the nursery one by one, immediately washing their hands. They are already registered with us and pick up their seedlings within a few minutes to limit contact. I am also training staff and we will also be using similar measures. It won’t be easy, but so far, the area where I am working in Tanzania has not reported many cases, so we are still proceeding, with caution.”

While the separation from her family has been difficult, Mutu has found a measure of comfort by connecting with colleagues around the continent, who are also suffering similar anxieties.

“I don’t think many people have thought about how many field workers across Africa are in similar situations. I know several, caught in countries far away from their families and having to go through self-isolation alone, not sure what will happen to their positions, or what exactly would happen if they do get sick, without their family. I have been speaking with [them] and it has been good to air feelings of frustration and uncertainty not just about returning to our home countries but also about the work we are doing.”

Both Mutu and Quainoo-Appiah have also had to get creative when connecting with their partners in order to provide much-need support and encouragement.

“I regularly check in with [my husband] to see how he is doing mentally, emotionally, and physically during what, I think, has been one of the most demanding phases of his life – playing the role of a single parent – taking care of all the housework, cooking, cleaning, kids, pets, and homework! We tend to get caught up in logistics when I call and so we’ve tried to have a weekly call where we just talk about how we are both doing with where we’re at, and the small things we can do to make life more manageable,” says Mutu.

With her husband on the other side of the Atlantic, Quainoo-Appiah has had to go the extra mile to make the most of their shorter days together.

“If he was [working] in Ghana, we could wake up together or go to sleep together but, with the time difference, my mornings are lonely and his evenings are lonely.”

“Sometimes, I just find myself leaving the video on in a corner of the house so he can see what we’re doing and I think that makes him feel a bit more involved. I just don’t want him to miss out on anything, even the small moments,” she confesses.

While some countries around the world have begun cautious but calibrated attempts to return to normalcy, slowly lifting restrictions and encouraging people to go back to work or school, many African nations are still bracing for the worst. But for families like Mutu’s and Quainoo-Appiah’s, the future remains worryingly uncertain, particularly with the borders between them and their loved ones firmly shut and relevant repatriation policies unannounced.

However, true to the legendary resilience of the women of this continent, they both maintain that, whatever happens, they will be with their families again.

“We have to dwell on the positives, for now, and hope that there will be many more moments in our lives that we’ll be able to experience together,” Quainoo-Appiah reflects.

Author’s note: At the time of publishing, the Kenyan government announced its intention to completely close its borders with Tanzania, where Corrie wa Mutu is based. The implementation of this closure, and its consequences on those seeking to return to the country, were yet to be established. Meanwhile, all non-essential travel to the United Kingdom was suspended from Ghana until the end of May with consular services between the two countries temporarily suspended.

– By Marie Shabaya