In May, Edvard Munch’s The Scream sold for $120 million becoming the most expensive painting to be sold at auction. A week later, Mark Rothko’s Orange, Red, Yellow sold for nearly $87 million. Irma Stern’s Two Arabs sold for R21 million ($2.5 million) last year, the highest price for a painting sold at auction in South Africa. Eleven of the 20 highest prices fetched at auction in the world and nine of the 10 highest prices in South Africa have occurred since 2008.

The near-collapse of the global economy didn’t stop the market reaching its highs. Wealthy collectors remain wealthy. And top-quality items appreciate even in poorer market contexts. Fine art auction house, Strauss & Co, reported a boom in 2010 with a turnover of R187 million ($22.3 million) and a strong market for 2011 making only slightly less at R170 million ($20.2 million).

Despite hammer prices being up, masterpieces are out of the price range of many collectors and dealers. The high end of the market is one part of the story, it’s the segment that appeals to the popular imagination, and to those of us who are so insanely disconnected from the real world that we continue to hope that one day, we too may be able to buy a Malevich or a Twombly.

“The run-of-the-mill part of the market is in a sorry state,” says fine art expert and auctioneer, Stephan Welz.

“At this end of the market, dealers have in the past bought a large percentage of works as stock-in-trade to sell to the average salaried person who wants one or two nice pieces on the mantelpiece.”

It would be silly not to admit we’ve been affected. Those works least affected are those with rarity value; anything decorative has been devastated,” adds Mark Read, director of the Everard Read gallery.

Steven Wlz at the Strauss and Co auction

Given then that the Old Masters and historic paintings are too expensive for most collectors and dealers and, of course, there are fewer of them, dealers both abroad and locally have turned to contemporary artists, which are normally fragile in the secondary market and a highly speculative sector.

For the last two years, contemporary works have topped auction sales at Christie’s—an international company offering art auctions and private sales to clients. In South Africa, artists like Robert Hodgins, William Kentridge, Walter Battiss and Erik Laubscher are fetching good prices as the market broadens. But there are no guarantees of a handsome profit, even if you’ve studied past performance prices, says Welz, and those are less available for contemporary than older works. Some wonder, too, about the staying power of this market compared to those works time has already validated.

Markets, of course, depend not only on buyers, but also on sellers.

“When the market isn’t favorable, sellers are reluctant to sell, and they’re usually in a position to choose their market,” says Welz.

What’s more, sellers don’t know where else to invest their money since opportunities are currently few—stock markets are down, rates on savings accounts are low and interest is taxed, even gold has been volatile.

A conversation between Sotheby’s chair of contemporary art for Europe, Cheyenne Westphal and an anonymous American collector as reported in the Wall Street Journal serves to illustrate the point: “I phoned him up and told him, ‘Do you realize that in the present market, we can get you $50 million for your Rothko?’ There was a very long silence on the other end of the phone. Eventually, he replied, ‘Well, Ms Westphal, that sure is tremendous news. But what the hell would I do with $50 million in the bank?’”

To try to predict prices and understand trends, we turn to the market intelligence provided by public auctions (auctions are fairly transparent compared to private sales, prices are published and annual reports are available) and historical price indexes. But, even armed with these prognostications, one feels uneasy in generalizing across the market.

Part of the reason that trying to draw any conclusions about the health of the art market is so difficult is because that very term is a misnomer. A number of small markets combine to form the art market and while Old Masters are selling, demand for contemporary or modern art pieces may be declining; buyers supporting the fine arts market are not the same people who are buying decorative art.

The Wall Street Journal last month quoted Christie’s international as saying its art business had proved resilient and that a growing population of super-wealthy collectors were sustaining demand for top works. “We have not seen the global economy affect our business,” said Steven Murphy, Christie’s CE. The Mei Moses All Art Index, which measures art market returns by tracking the sale and resale of major art works, mainly in New York and London, claimed an 11% return for investors in 2011, outpacing stock market returns for a second consecutive year. But the problem is that not all art performs equally and most art never gains enough value to be represented at the kind of auction that index compilers track—it’s an incomplete picture. So studies like these fail to provide any proof that art is a solid investment generally.

Some economists explain the market’s relative buoyancy, saying fine art isn’t part of the global economy. Rather, they say, it is part of the booming economy of a set of super-super rich individuals or ‘Ultra High Net Worth Individuals’ who are just growing richer. For these people, and because a painting is singular and no one else can own it, an astronomically expensive work does an almost unparalleled job of saying just how wealthy and cultivated they are.

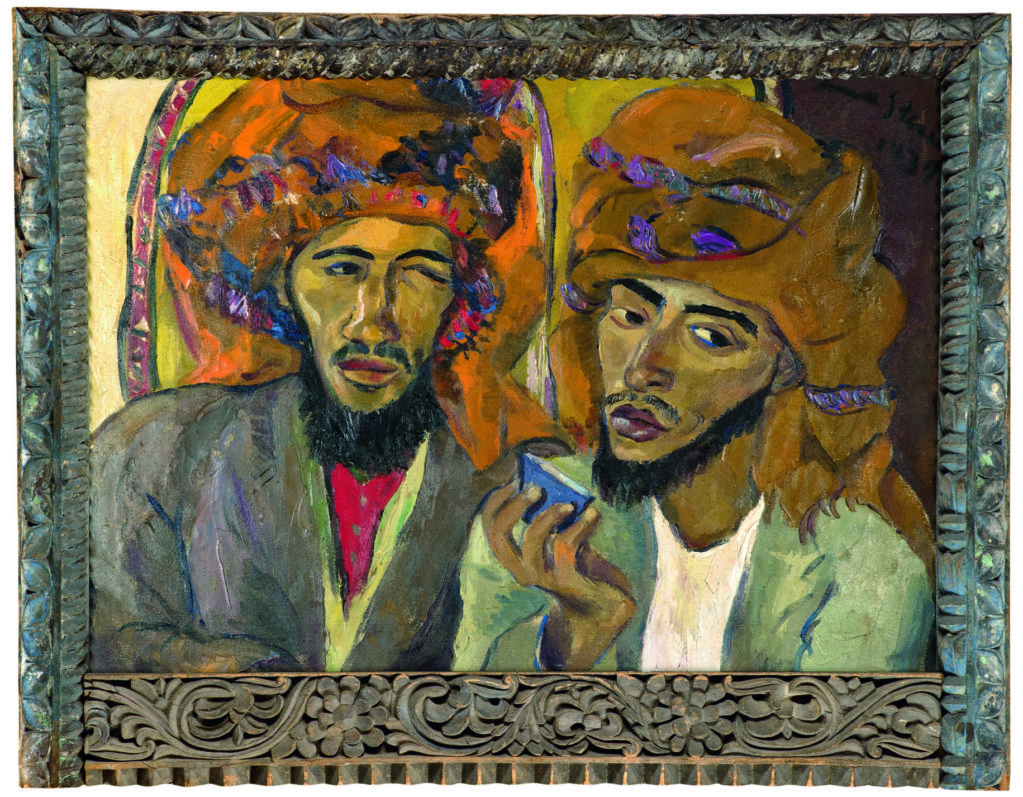

Let me illustrate what I mean. As I stood in front of the Stern on auction, Arab, I felt a little let down. It was small (66,5 x 65,5cm) and it was beautifully painted, the frame hand-carved, but I couldn’t help asking myself, ‘How can it possibly be worth R9 million [R17 million ($2.0 million) as it turned out]’, and that’s the thing, it isn’t, it signals that you’re spending money, squandering money even because what you’re buying can’t be worth that much. And it’s this fact, the fact that it isn’t a sensible way to make money that drives the trophy hunters.

But perhaps in comparing Arab to the value I would place on a house, I would be too narrowly defining an investment. Today, the value of an artwork is often determined by collectors for whom there is nothing more at stake than making money. Previously, critics and connoisseurs had some influence on which pieces were perceived to be good. “Today’s art market is by and large misinformed,” said veteran advisor Thea Westreich in the New York magazine. “People are using their ears, not their eyes, to select works, buying based on market trends rather than art-historical standards.”

The critic, Clement Greenberg, was right when he said of culture and its place in the economy of life, “a poor life is lived by anyone who doesn’t regularly take time out to stand and gaze… without any further end in mind, simply for the satisfaction gotten from that which is gazed at…” He also said, “there are, of course, more important things than art, life itself, what actually happens to you”.

Overseas, the art market is huge and growing—there is a new class of people buying art. But in South Africa, the market is incredibly small, says Stefan Hundt of Sanlam Private Investments’ art advisory service. “If we have 5,000 serious buyers, it’s a lot,” and adds it’s for this reason that an art fund wouldn’t survive.

If the economy continues to stagnate, Welz and Read anticipate tough times to come. Even if it starts to grow, since the art economy lags behind the normal economy by about a year, it will be some time before private collectors and corporates have any disposable income to invest in art.

Let art be first a pleasure, the prevailing wisdom goes, then an asset. That way, the quality verdicts of the public, which make it a capricious investment, won’t matter so much. As an asset market, says international-capital-markets expert Amir Shariat in the New York magazine, “art remains non-transparent, overly prone to taste and fashions, and extremely illiquid. People forget that illiquid doesn’t mean ‘low price’. It means ‘no price’.”

Perhaps art isn’t even an investment or perhaps it’s an investment of a different nature. There’s an intangible pleasure in owning a painting and, unlike stocks, art doesn’t earn dividends and it costs to keep—you have to look after it, make sure it doesn’t deteriorate and insure it and then there are steep transaction costs. Unlike other investments, the art object is unique, “detached from the sanity of a cause” in Samuel Beckett’s words (though less so when we look at overpriced contemporary works like Damien Hirst’s, which are made with the sale in mind). In being inexplicable, to take Beckett’s reasoning to its conclusion, art objects may be a source of enchantment, and in following the trading of these in the financial arena, emptied for a moment of the wonder they can inspire in quieter moments, we can forget that.