Uncle Ebo Whyte is a six-foot-tall, unassuming looking man. You could mistake him for a steward of the theater rather than the father of it. He speaks in a soft but confident manner but has an attention to detail that is slightly intimidating as we sit down in his cosy office to discuss his journey as one of West Africa’s best known playwrights. Surprisingly, the love of his life arrived by accident.

“I didn’t have the confidence to join the drama society because it had all the popular boys and I suffered from inferiority complex in those days, so I couldn’t enter their circle. One day they needed someone to fill in during their rehearsals and I happened to be the only person standing in the window watching them. What the director didn’t realize was that I had memorized the lines. It took the director only five minutes to realize I would be able to give a better performance than the previous actor he had cast for the role,” says Whyte.

In 1974, Whyte wrote his first play. It was called ‘Man Must Live’ and depicted the struggles of two sisters whose father died and left them penniless. The story had echoes of his life. As the first of five boys, Whyte grew up in a competitive household. When he was 15 years old, his father passed away and his family lost everything.

“I was devastated when he died, I think for a year or two I was totally lost. Those were the days before the Provisional National Defense Council (PNDC) law came into place, for when a man died intestate, which protects the widow and the children. So, all the extended family took everything from us apart from the house we were living in,” says Whyte.

After studying statistics at the University of Ghana, Whyte almost got chartered but decided last minute against accounting. He wanted a life of spinning stories into gold.

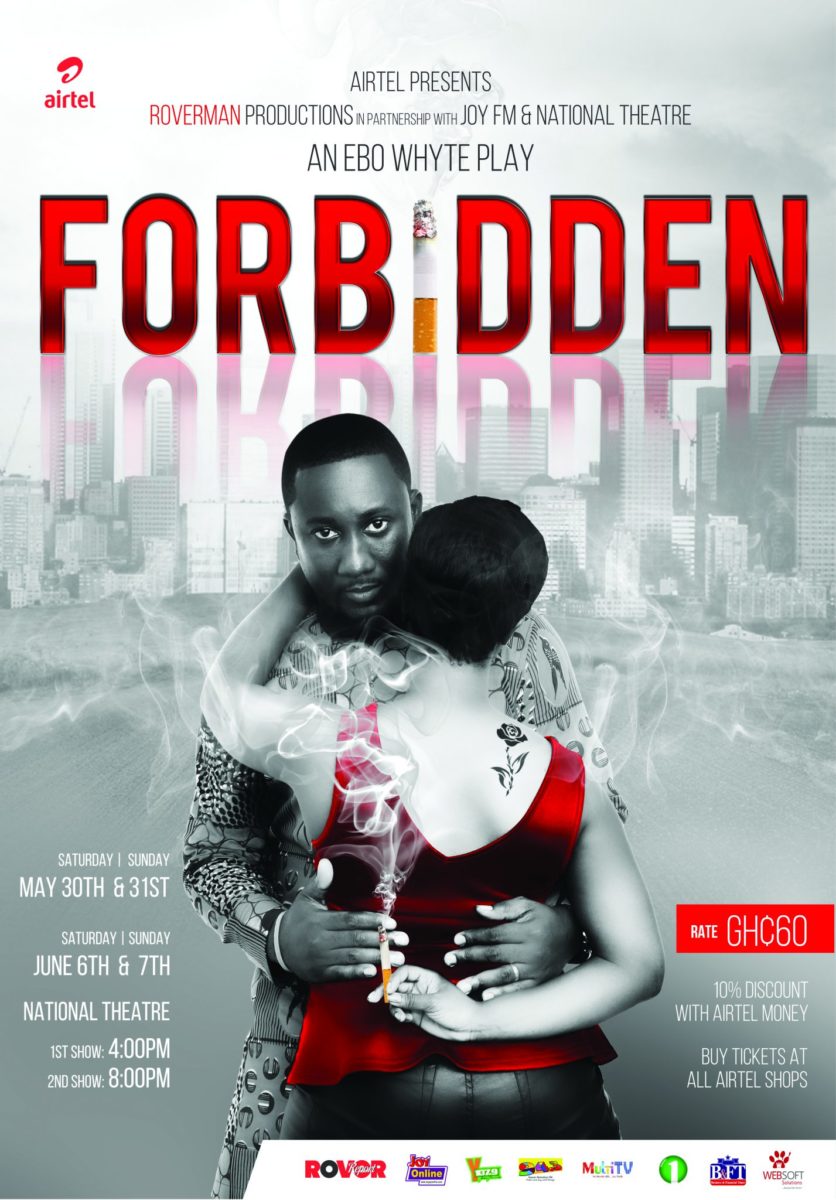

“Roverman Productions started in 2008. The problem was that there was no template for me to know how I could make theater production into a business. My first three attempts of making this work were financially disastrous because I came from the background where drama production was free, hence putting together plays you had to sell was difficult, thank God I learned how to do it,” says Whyte.

He began alone and now employs 15 permanent staff and an 80-man production team.

Getting an audience for the plays was the easy part. The difficulty for Whyte was securing money for the quality of production he wanted. Whyte wanted his production house to produce quarterly plays and to become big enough to be a name in Africa.

Tourists are a big market. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council, Ghana attracted 925,000 international tourists in 2015. In 10 years, international tourists are forecast to total 1.38 million. He reckons about 45% of the holidaymakers in Ghana come to his plays.

Then there was the tougher nut of corporate Ghana to crack.

“Gatekeepers in corporate Ghana could understand musical concerts but they could not understand how theater would work. We were the first company to pioneer theater in Ghana. When they saw how many people we were able to pull, they came easier and it became a much easier sell,” says Whyte.

“We have huge goodwill in the various boardrooms in Ghana. What is happening now is that a lot of the big companies are being controlled from outside Ghana and because the people pulling the strings are not in Ghana, they do not care about spending money here because they do not know about what is on the ground. So it is usually a budgetary issue with companies.”

Eight years on and there are still problems. Like the rest of Ghana, the theater is hampered by another drama – power cuts.

“One terrible moment was last quarter when the lights went out at the national theatre in the middle of the production. We were using a generator, which stopped an hour and half into the production. I think I died inside. Not because we couldn’t solve the situation because we got the power back in 30 minutes, but because of the excellence I look to achieve. I do not want my patrons to take certain things for granted. They should expect to pay for their tickets and nothing will go wrong. They do not need any excuses and I do not want to give them any. The fact that I could not deliver a production without a hiccup was very bad,” says Whyte.

George Ofori runs an art gallery in Accra. His family owned a theater business in the late 70s when stage productions were popular.

“The theater business died during the military rule where there were widespread curfews. My father and a lot of other production houses had to find new ways of making money back then. After that, the theater business has never really bounced back and a lot of people have struggled to make the business viable,” says Ofori.

“The theater business in Ghana is still very much at an evolving and developmental stage with a gradual effort towards audience cultivation. The potential for growth into a viable, consistent and highly rewarding industry is very high. Presently, Roverman Productions is the most identifiable theater entity owing to the consistent quality productions over the last eight years,” says Kabutey Ocansey, Head of Business Development for Roverman Productions.

For those closest to Whyte, his passion for the business is palpable.

“He is a perfectionist and passionate about theater and feels that Ghana has the talent to compare with any theater group in the world if we so desire and are willing to work diligently,” says Felicia Mensah, Customer Relations Coordinator at Roverman Productions.

For Whyte it is not just about business. It is about families dressing up and sharing in their cultural heritage. The golden tradition of families sitting by the fireside and sharing stories may be long gone in the world of the cell phone, but there is a renaissance of storytelling in Ghana and Whyte is responsible for this. As he recounts his journey, the quiet and reserved man is clearly in his element.