The drive to Zimbabwe’s capital, Harare, is slippery in light winter rain. The sky is full of rich grey clouds; on the ground, the country is paved with cracked roads, poverty and struggle.

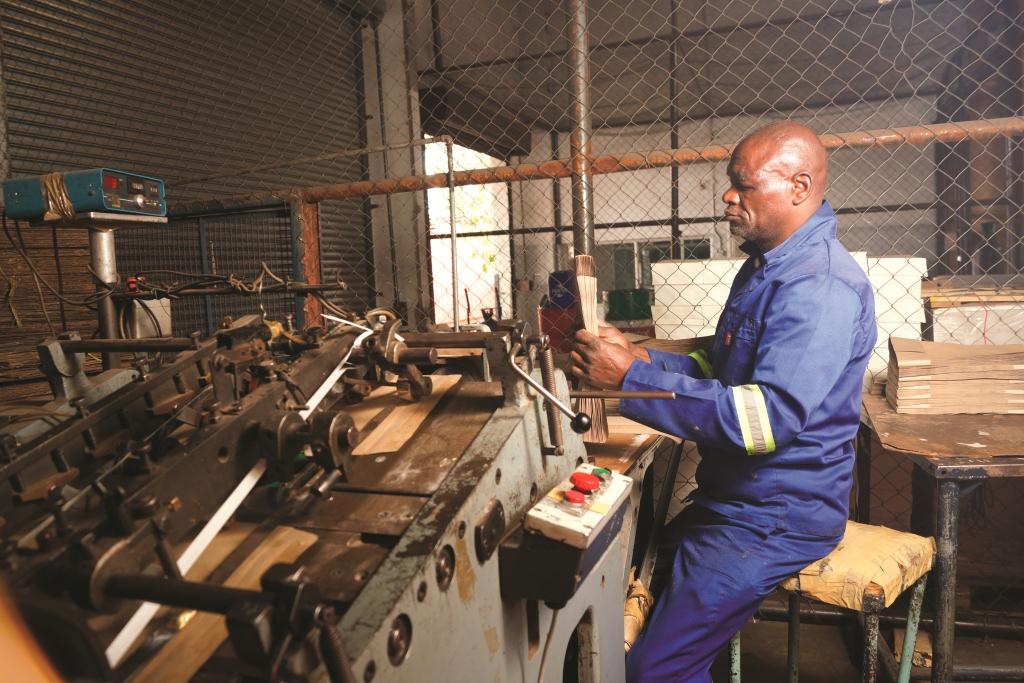

On the way, many businesses are boarded up, their paint peeling and doors closed. As we arrive in Harare, many shops are packed with imported goods, but, in Workington, an industrial suburb in the south west of Harare, there is a stubborn survivor – a factory that has been producing Zimbabwean products since 1978.

Rank, founded by Amish and Ketan Naik’s grandfather, is the leading stationery supplier in Zimbabwe. It also distributes paper and board to the printing industry and manufactures plastic goods. Their grandfather arrived in Zimbabwe, via Zambia, from India in the late 1960s.

Business in Zimbabwe thrived until the country hit hyperinflation in the early 2000s. Although the factory is stacked with goods and 102 employees, like many businesses here, the lack of money in the banks threatens its survival.

The company has ample money in the bank but it can’t take it out to buy raw materials.

“We are being optimistic because if we are being pessimistic about this whole thing it won’t end well. We have been breaking even for the last six months, last year we were 3.5 percent down. We believe this year we are going to be 20 percent down or probably more,” says Ketan.

The company will cut the number of goods they produce to survive. They say they will try managing their overheads, because their staff is the last cost they want to cut.

“We will work within our means; effectively we will produce what we can in terms of what we can purchase in terms of raw material. It also means we have narrowed our gains down, guided by our industry,” he says.

It’s been a struggle over the last decade to keep the doors open.

“We had to scale down to the minimum. We were down to almost 10 percent, or less than 10 percent, because we were trading simply to pay wages. In the past, during high inflation, it came down to where our staff would just come in to have a meal because by the time they got their money, and went home, it was worthless,” says Amish.

The Naik brothers say their biggest threat is the weak economy. In a way, the recent ban on basic goods imports, which everyone is complaining about, may help companies like them.

“We estimated, for example, that in the exercise book industry, 40 percent was being imported from South Africa and 60 percent bought here. The tariff protection came in August 2015 and there has been a shift, we can say nine to ten percent or so increase, on our manufacturing, and the statistical growth shows it boosted our production,” says Amish.

Another Zimbabwean entrepreneur, Frank Buyanga, with a finger on the pulse, featured in FORBES AFRICA in 2013 when he had an Interpol notice imposed on him by government. He is back in business in Zimbabwe and thinks that the ban on imports is sensible as it protects home-grown industry.

“The advantages of doing business in Zimbabwe are the highly educated and generally honest workforce, good infrastructure and sophisticated business climate, especially when compared to other countries in Africa, except Botswana, Namibia and South Africa. The main disadvantage is the increasing level of corruption,” says Buyanga.

Ketan agrees the ban could work; but not with a weak economy.

“It doesn’t help as much because where there is a shortage created by us not having raw materials, the smugglers start because they now see an opportunity. If there is a shortage in the market of the product, the pricing would mean 50 percent mark-up”.

Even Rank’s suppliers are not happy.

“Our suppliers are saying to us that, ‘Guys we have supplied the goods you need to pay for those’. We have sort of done a reverse circle where initially we had to pay upfront; we built our relationships so that they provide us with credit facilities. Now we are ok, the credit facilities need to be reduced to zero and start paying upfront because we are not able to sustain them,” says Ketan.

Making a bit of money through exports into neighboring countries is not an option because it is expensive to manufacture products in Zimbabwe.

“A Malawian manufacturer, for example, would buy raw materials from the same places as us. But, we would pay let’s say $300 for a job yet they would pay less than $100 for that same job. How do we compete? Their expenses become lower, therefore their goods are cheaper.”

Rank is not the only Zimbabwean company running a tight ship.

On the other side of Harare, Melissa Mafunga, Managing Director at Hamilton Finance, says 30 to 50 people walk into their offices each day seeking to borrow money, most of these, struggling small business owners.

“Sometimes they come borrow money because they want to buy stock or pay a little bit of salaries. From here, I see that many small businesses are run on credit. Due to the cash challenges the country is facing, the default rate has risen by 75 percent this year. So we make sure we hold collateral before we lend out money,” she says.

Joyce Nousenga, General Manager at Hamilton Insurance, says business is slow because insurance is at the bottom of the list for companies.

“Even companies are slowing down on their purchase of insurance and most people opt for minimal cover, of which most of it is statutory. Business is tough for everyone, so much that they can’t even protect the little they have through comprehensive insurance,” she says.

We leave Amish and Ketan with hope that they will carry on breaking even in a country that is struggling to do so.