It’s a rough, tough, brutal business for an entrepreneur; you risk your neck in places where no one wants to go to find stories that everyone wants to know; it’s months of tedium and travelling where one slip can mean death.

This is the news business in Africa that is the life of Kenyan Salim Amin; it is also the cruel business in which his father suffered on his way to an early grave.

Amin will never forget November 23, 1996, the day word came through. His father Mo Amin, a legendary photojournalist, had survived many dangers in more than 30 years on the road, including the loss of an arm in an explosion in the Ethiopian civil war. His life came to a tragic end in the Indian Ocean.

“I was at the gym when I got a call from mum asking me to come home immediately as something had happened to dad’s flight. I only believed it after I identified his body in the Comoros,” he says.

Mo was on an Air Ethiopia flight home to Nairobi when hijackers took the plane. He tried to rally passengers to fight back but the plane ran out of fuel and ditched in the sea, off the coast of the Comoros, killing all but 50 on board.

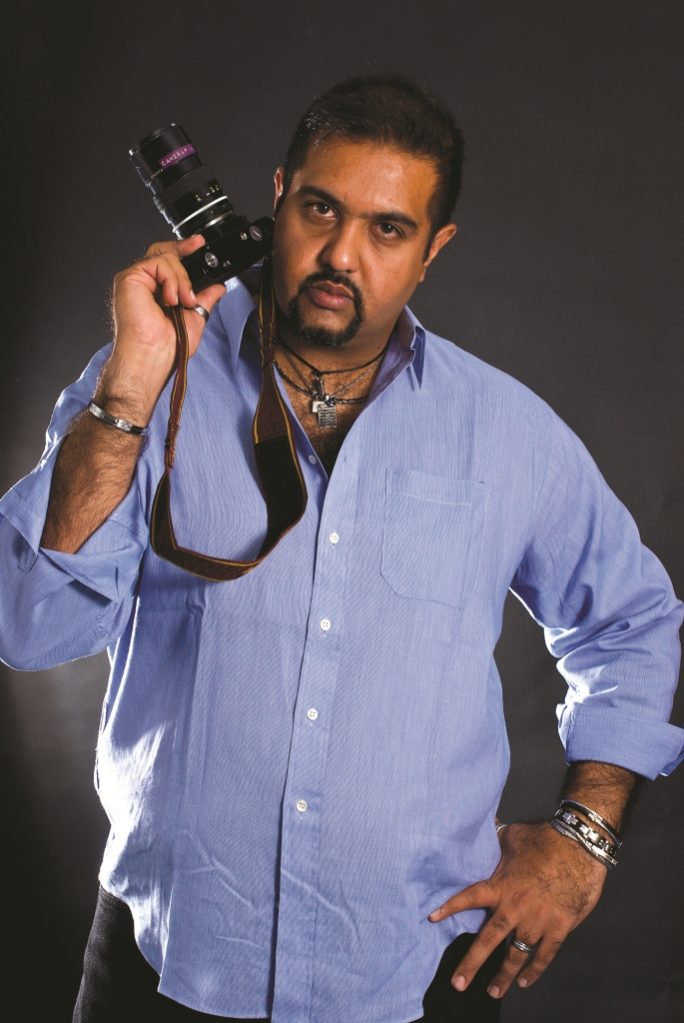

Entrepreneur, Photojournalist, Kenya, Salim Amin, March 2016

“He was still on his feet when the plane crashed trying to get the hijackers off the pilot as he tried to land in the ocean. The hijackers claimed they had a grenade but no evidence of this was found. Mo was flying from Addis Ababa to Nairobi. He had gone to Addis for a meeting with Ethiopian Airlines as we produced the inflight magazine,” says Salim.

Mo died side-by-side with a friend and fellow journalist. Brian Tetley, who was 61, was a British-born, Nairobi-based, king of the keyboard and bon viveur.

“Brian worked with my father for over three decades and they were very close friends. Brian was often the writer while my dad photographed the major news stories, and they also co-authored/produced over two dozen books together. They were like brothers and travelled all over the world on assignments together,” says Salim.

The plane crash cost Salim his father and mentor; the man who remained a mystery right up to his tragic death, an oft told African story of father and son.

“We had a lot of love between us but I hardly saw him and didn’t really know him very well… we didn’t speak much about personal matters, more about work.”

Taking up the camera, for Salim, was bittersweet.

“I started taking pictures when I was eight years old… that’s when he gave me his first camera,” he says.

With this camera, Salim took a picture that appeared in TIME magazine, making him probably the only 10-year-old African to ever have a picture published in a global magazine.

“I was amazed when I saw it actually in print! If I had had any doubts about what I was going to do before that, then those went out of the window when I saw my work in print,” says Salim.

He started working for the media company his father founded – Camerapix.

“My first pay cheque was from Camerapix… he paid me Ksh5,000 for my first month at work in 1992 (then around $100).”

Salim has no regrets in an unforgiving business.

“I don’t think I would want to ever do anything else… definitely I would want to be doing the same thing in another life.”

This is a trade where you can very easily die, unsung, chasing a story. Salim had his fair share.

“I remember being bombed by government forces in Sudan during the civil war, which was terrifying, the dangers of covering Somalia in the 1990s during Operation Restore Hope, the loss of my friends and colleagues Dan Eldon, Anthony Macharia and Hos Maina in Somalia in 1993, and the genocide in Rwanda which was the most disturbing and brutal story I had ever covered,” says Salim.

Eldon, an English-born Kenyan photojournalist, with Kenyans, Macharia and Maina, were killed by an angry mob in Mogadishu in 1993, in the days when occupying US forces struggled to keep order.

Another journalist who survived that violent day is Angus Shaw, who spent 40 years covering eight wars, from his base in Harare, Zimbabwe.

“We were at the hotel that morning when we heard an explosion five blocks away. We decided to go down and have a look,” recollects Shaw.

“The Camerapix crew drove ahead of us as we headed to the compound where the explosion took place and as we got there, we saw a swelling crowd. The crowd erupted into extreme anger after seeing the carnage and deaths after the bombings of that narrow street, they started throwing stones at our small press convoy yelling ‘Yankies go home’. Eldon had disappeared inside this angry crowd when they started throwing stones. Every photojournalist wanted the best picture so they hardly paid attention to the possible dangers.”

What followed will haunt Shaw forever.

“I saw a handful of people armed with AK-47 rifles firing shots and I saw a nice young man, Macharia, going down. He had been shot. We realized this was getting out of hand and we started driving away and at that point, they had started shooting at our car which was about 25 meters away.”

Days passed with no trace of the 23-year-old Eldon, last seen disappearing into the angry crowd.

“One morning we woke up to the sight of Dan’s bloody shoes at the doorstep of our hotel. This was a warning to us.”

Shaw says, as they were wrapping Eldon’s belongings, Mo reminded the press corps that covering atrocities was more than reporting numbers.

“When you start wrapping the belongings of your own, then you discover that that’s what people go through all over the world,” says Shaw.

Salim wishes the continent that gave birth to many great journalists could spare a thought for their hardships.

“I wish Africans would celebrate journalists more… we are seen as ‘lowly’ people and in a corrupt profession by many around the continent, and unfortunately even African media organizations do not celebrate African journalists enough. My father was recognized and decorated more outside Africa than within. We should do more and maybe have a commemoration day each year for African journalists that is a celebration of their sacrifices and contributions.”

Salim found himself at the helm of his late father’s business at the age of 26.

“I had no experience at running a company; luckily my father was good at filing all his work so I had to study his documents and correspondences,” he says.

“The first day was chaotic. We had to re-register and restructure the company. We started by giving everybody their dues, close the company and re-employ them again under the new registered company with new shareholding. It never really struck me that I was now running the company, it just happened as there was no succession plan. I had no choice.”

Salim concedes he has to move with the times.

Media and development expert, Rashweat Mukundu, says the internet is changing the news business.

“Traditional models of doing business are being challenged, yet some traditional elements, that include the human touch, will remain necessary, yet more enhanced by ICTs. We are in an era of either business adapts or dies,” he says.

Bruce Mutsvairo, media professor at Northumbria University in Britain, says Africa should plough its own furrow.

“Our innovations should underscore, support and provide the basis for Africa’s cultural and economic needs. We have to come with our own innovations, even if they get rejected in the West.”

In Mo’s day, it was all about hard news, hotspots and wars. The news business these days is more about fashion and business, says Salim. With more than four million images of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, and 8,000 hours of video footage, Camerapix Archive is the largest library in Africa.

“Our only asset is our archives. I am not so sure I would attach any monetary value on the company. It’s a family business that I would not dream of selling.”

Like many in the media industry, Salim struggles to make money as there is a lot of free content floating around.

“We are producing a lot of content; it’s not giving us much revenue as yet. So we have to sell our content to multiple broadcasters. There are more opportunities presented through mobile devices but expensive data remains the main impediment.”

Salim plans to ease himself out of the business to make way for the next generation.

“We did the first private-public partnership with a local university where we are also helping develop their postgraduate degree. We have just moved into the Multimedia University where our production team is housed; in exchange we are helping them develop their master’s program.”

Another chapter for Africa – a great story that many journalists have paid with their lives to tell.