It could have come straight out of a novel. Twenty men, most of them Congolese asylum seekers, stand accused of plotting to overthrow their head of state, Joseph Kabila, from a base deep in the South African bush.

When news of their arrest broke last year, the headlines flew: “Congolese Crisis Comes Knocking at South Africa’s Door”, “Congo Dissidents Stung By Hawks”. The men appeared at the North Gauteng High Court in Pretoria with a supportive crowd of countrymen behind them. They denied the charges.

The peculiarities of this case may impact the future of mercenary law in South Africa, says Cerita Joubert, lawyer to three of the accused.

“It’s a very good test case… because the definition of mercenary activities [in the Act] is to actually actively engage in combat… and in all the previous cases in South Africa regarding Foreign Military Assistance there was actually a guilty plea by the accused.”

But there are other concerns regarding the investigation that led to the men’s arrests.

“The whole setting of a trap [by South African Police] makes a very nice test case for how far you [are] allowed to go before crossing that border. Our argument is [that] a line was crossed,” she says.

Thesigan Pillay, lawyer to 14 of the accused agrees.

“[They] deliberately [lured] these people to commit the offense to use them as an example… whoever wants even to think about [planning a coup] in South Africa [will] face the full might of the law. Or it could be that there is complicity from the hierarchies of the South African government who are encouraging this [saying] ‘arrest them, detain them because we have interests in the DRC and we do not want South Africa to be used as a platform for dissent against Kabila.’”

However, a source close to the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), which is currently presenting the case against the men from Congo, claims the prosecution is simply following its mandate.

“Any action for the unconstitutional change of a government would obviously result as Foreign Military Assistance… we are trying to get rid of this culture of mercenarism in South Africa.”

Joubert and Pillay also insist that, for their clients, money was the main objective.

“The entire thing wasn’t about a coup d’état, it was an opportunity to make money,” claims Pillay.

The story of the Congo 20, as the group is also known, is a convoluted one. To understand why, it helps to return to the very beginning.

Early last year, the men from Congo are accused of convening in Johannesburg to discuss the fronting of an obscure rebel unit to remove the Kabila regime through ‘conventional warfare’. The group’s leaders emerged as James Kazongo, a naturalized American citizen, and a man who claims to be Kabila’s half-brother, Etienne Kabila. General William Amuri Yakutumba, whose whereabouts are currently unknown, was implicated as the group’s military head.

It was claimed, during the trial, that around 7,000 to 9,000 rebel soldiers were loyal to this dissident organization, Union des Nationaliste pour le Renouveau or the Union of Nationalists for Renewal (UNR), based in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Over a five-month period, beginning in September 2012, key members of the group made contact with men they believed to be sponsors interested in mining concessions once the Kabila regime was toppled.

The ‘sponsors’ were actually elite undercover agents in the South African police known as the Hawks. They caught the Congolese in a sting operation.

New information obtained by FORBES AFRICA points to a very different version of events.

In September 2012, accused number four, Kabuka Lugamba Andrian Kilele met Carlos Nkuka, a Congolese man living in Angola, who claimed to work for an Umkhonto we Sizwe veteran, going by the name of Andries Pienaar, later revealed to be part of the sting operation.

Nkuka convinced Kilele to introduce his friend Etienne Taratibu Kabila, alleged son of former Congolese president, Laurent Kabila, who lived in Cape Town, to his boss. Nkuka and Pienaar said they wanted to go into ‘business’ with Kabila.

A few days after making contact, Kabila traveled to Johannesburg to meet with Nkuka and Pienaar at their request. They met first at a fast food restaurant on Louis Botha Avenue, a major thoroughfare that links downtown Johannesburg to Sandton, the city’s business district.

The men then moved the meeting to Kilele’s house on Nugget Street, in downtown Johannesburg, where Pienaar first brought up the mining proposal.

“[He said] I have my people who always wanted to exploit mining business in your country… among Congolese here, I haven’t found one who has got influence in your country,” a source at the meeting tells FORBES AFRICA.

Nkuka and Pienaar wanted to harness the influence of Kabila’s name to take over key mining operations in the DRC already controlled by major rebel groups and government forces. This was their ‘business’ proposal to Kabila.

Days after Kabila returned to Cape Town, Nkuka and Pienaar met with Kilele in the garden suburb of Norwood at a local restaurant. This time Kilele brought along a friend, Lunula ‘Patrick’ Masikini, accused number two. They were instructed to drive to Pienaar’s house and as they were driving they noticed two cars were trailing them: one blue, one silver. They all pulled up at Pienaar’s front yard.

Masikini and Kilele were led into the dining room where they were questioned about Kabila’s relationship with his alleged half-brother, Joseph. After a long conversation about the Kabila brothers, they were shown photos of gold purchased from a mine in Goma, a city on the northern banks of Lake Kivu, by the driver of the blue car.

The case investigator, Lieutenant Colonel Noel Zeeman, was at this meeting. While undercover, Pienaar told the men from Congo that Zeeman was their ‘boss’ who lived in Europe but came to South Africa often.

A few days later, they reconvened. Pienaar, with Zeeman and Nkuka, informed Kilele and Masikini that Kabila had agreed ‘to do business with them.’

The men returned to Norwood and met with undercover agents James Jansen and Joe Bressler for the first time. Pienaar waited in the car.

For the second time, Kabila traveled to Johannesburg to meet with his ‘business’ partners. But this time he was wary. He sent Kilele to meet with Jansen and Bressler at an address sent to him via SMS. After this meeting, an offer was made.

According to a source, Jansen offered Kabila $30,000 to scout mining locations in the DRC. He also emphasized the need for security at the mines, saying that Kabila needed to be ‘with people carrying guns’. The Hawks asked for images of the mines as well as photos of Kabila’s ‘people’ along with the names of ‘10 to 15 people for training’. The plan was to force President Kabila to ‘a point of negotiation’ for mines under his control.

Kabila was hesitant so the offer was increased to $79,000 in two instalments.

“First they will hand over [to Etienne] $30,000 and $49,000 will be [handed over] once he [brought] people for the training,” claims a source who joined the negotiations.

Kabila did not bite, instead withdrawing completely, suspicious of the Hawks and their interest in his name.

“He said… ‘I am not going to continue with these people because why James [Jansen] asked about my brother Joseph [Kabila]?’… I am [certain] these people must be police or Kabila’s agent.’”

Kabila returned to Cape Town and was not seen again until he handed himself over to police in February 2013.

At this point, Kilele decided to continue with the partnership recruiting some friends, also facing charges, to take over from Kabila. He introduced his friends to Jansen and Bressler in Midrand, at a restaurant suspended above the N1 highway, the road that links Johannesburg and Pretoria.

Jansen talked about the money they could all make, if they took ‘two or three provinces in the DRC’ and ran the mines. Later that night, the men received an offer from the agents that they found hard to refuse – $300,000 – more money than any of them had ever imagined.

“Hearing this amount of money… I said I have to do whatever they want to get the money,” admits a source at that meeting.

Kazongo was central to obtaining the money, claim a number of sources. The alleged leader of the group knew Maskini through his sister in Belgium. At some point, he was preparing an affidavit for Masikini to relocate to the United States, where he has lived for 32 years, but the move never happened.

Kazongo was to play a small role: meet with the agents, posing as ‘President’ of the group, to collect the money. For his trouble, he was promised $100,000.

The UNR’s alleged military head, General Yakutumba, founder of the Mai Mai Yakutumba rebels in South Kivu, was forced into their plans.

“These guys [wanted] a person who has influence to lead… [and] some photos of soldiers and also Yakutumba’s image because they checked him on the internet… that’s where the idea of Yakutumba came from,” reveals a source.

In January 2013, Kilele met with the general at an undisclosed location just outside Uvira, a town that flanks the northern edge of Lake Tanganyika. For the promise of $20,000, Yakutumba and his soldiers posed for photographs and video with Kilele. This would later be used as proof of the group’s military prowess.

During the same trip, Kilele took photos of mines and brought back gold samples. This, he hoped, was evidence enough for ‘the sponsor’. He handed over the evidence, with Masikini, to Jansen after returning South Africa on January 22, 2013.

Many of the Congolese men implicated in the coup charges claim they were recruited by Kilele and another man, accused number 13, David Bakajika, to attend anti-rhino poaching training. They say they knew nothing about the agreements Kilele made with the agents.

“The training was supposed to last for seven weeks. Upon completion of that training we were supposed to receive a certificate and a lump sum of $2,500 for each trainee. Furthermore, I was told by Kilele that there will be opportunity for employment as security in the farms of South Africa, so I wanted to use my vacation time to get the certificate and the money and go back to DRC,” says a source close to Kilele.

On February 4, 2014, a day before their arrest, 19 of the Congolese accused departed for a fast food restaurant to meet with Jansen and Bressler. Masikini drove Kazongo and Kilele to the restaurant. The other men took public transport. When they got there, they felt something was wrong. A source claims that there were four men accompanying the agents and all of them were carrying pistols.

The men from the DRC were then driven further north on the N1. They didn’t know where they were going. They passed Pretoria and drove for hours into the bush.

The journey ended at a farm in the middle of nowhere.

“It was just a camp with some tents,” says a source on the trip.

The men were given military fatigues, boots and coats. On a flipboard was written ‘Coup d’état’ and ‘questions which needed to be answered’ in both English and French.

They were told to familiarize themselves with the place as they were going to spend seven weeks there, but the stay was cut short.

“[They] pointed a gun at [us] and said ‘no one is allowed to move around,’ says another source.

They felt they were in trouble.

“We knew then that we were with the wrong people, at the wrong place, at the wrong time.”

While at the farm, they met another face they later would see in court, the trainer, ‘Nick’.

“He introduced himself saying he is not a good man as we might think. He is a killer and he [doesn’t] know how many people he has killed in his life and he [doesn’t] trust anyone; only his cousin, who was holding a camera in front of us,” claims a source.

Nick had helped train security contractors in Afghanistan. He told the men from Congo that he had recently returned.

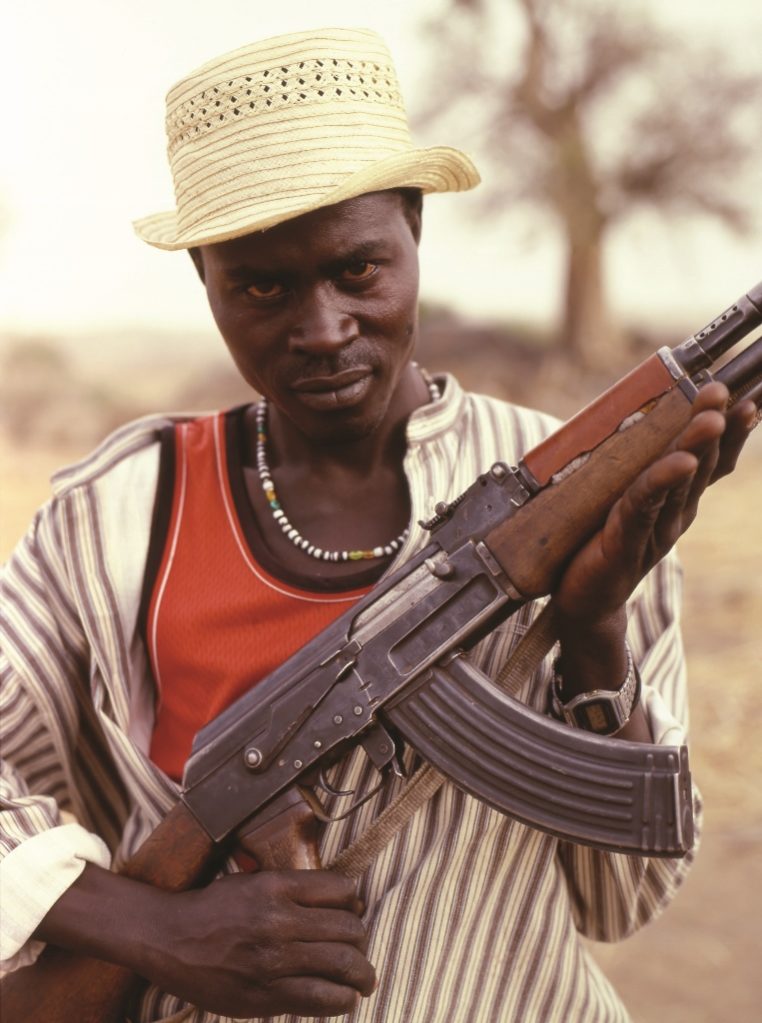

An ‘agitated’ Jansen then appeared with a wooden box containing ‘huge guns’. He instructed them to put on the fatigues, grab a gun and pose for photographs, which were later used against them in court.

At 4:30AM the next morning, the men were summoned from their tents by men in balaclavas. They were told they were going to meet the ‘sponsor’. Instead they met a familiar face with a police identification card who introduced himself as ‘Lieutenant Colonel Noel Graeme Zeeman’.

The men shuffled into a police van and were returned to Pretoria. In the car, a translator with the police confirmed their fate.

“Vous étés sous L’arréstation!” she said according to a source who was in the police van.

The men appeared at Pretoria Magistrate’s court two days later. After a month long battle, they were denied bail.

The Congo 20 last appeared in court in late October. Their lawyers expect the case to conclude early next year.