It was a sombre and belated ceremony. On August 19, after years of negotiations, South Africa welcomed home the remains of Nat Nakasa nearly half a century after he died after falling from a hotel window in New York. Nakasa was reburied on September 13 in Heroes’ Acre in Chesterville, Durban. The gravesite is a few kilometers from where Nakasa grew up.

CHESTERVILLE, SOUTH AFRICA- AUGUST 19: Minister of Arts and Culture Nathi Mthethwa, SA National Editors’ Forum executive director Mathatha Tsedu and Kwa Zulu Natal MEC for health Sibongiseni Dhlomo on August 19, 2014 at King Shaka International Airport in Durban, South Africa. The men attended a small ceremony at the airport to welcome back home well known late journalist, Nat Nakasa whose remains were brought back from the USA to be reburied in Chesterville Durban. (Photo by Gallo Images / The Times / Tebogo Letsie)

In October 1964, the 27-year-old Nakasa enrolled at Harvard University to study journalism. It meant he left South Africa forever as his government denied him a temporary visa. Nakasa was the second African to receive the Nieman Fellowship at Harvard University. The other was his colleague Lewis Nkosi. Nakasa’s death in exile remains a mystery.

At the time, Harvard University made a statement saying Nakasa committed suicide because he was homesick and depressed as the United States (US) government refused to extend his stay. But there was speculation that Nakasa, who was believed to have been watched by intelligence services, could have been pushed from the high hotel window.

Although Nakasa had no political allegiance, the apartheid government feared that he worked for the banned revolutionary organizations of Nelson Mandela and Robert Sobukwe.

“As I have never been active in politics except as a journalist, I expect no difficulty in obtaining a passport,” Nakasa wrote to the Nieman Foundation.

“If I shall leave this country and decide not to come back, it will be because of a desire to avoid perishing in my own bitterness – a bitterness born of being reduced to a second-class citizen,” Nakasa wrote in a column before he left South Africa.

Former journalist and academic, Professor Keorapetse Kgositsile, knew Nakasa well. Kgositsile, who was in exile with Nakasa in the US, first met him in the early 1960s when he worked for the left-wing publication The New Age and Nakasa for Drum magazine in Johannesburg.

“The general assumption is that Nat committed suicide. But I am not convinced that he did. As I have said before, I have no evidence to argue that he didn’t but also there’s no concrete evidence that he did. And knowing him, and the general African attitude towards suicide, especially our generation, it would be very strange because I don’t know of any South African who committed suicide around that time. I find the issue of suicide very problematic… It was misguiding that Nakasa wanted to return to South Africa during apartheid. He understood clearly he would not be allowed back. Those who said he wanted to return were undermining his intelligence,”

says Kgositsile.

“I respected Nat because he didn’t have any complications. He was what he was. He was humble, almost reserved, quietly spoken, honest and frank. He was almost withdrawn. When you met Nat, the man was not different from Nat the writer. He wrote what he believed and lived.”

South African musicians living in New York, Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela, and photographer Peter Magubane raised money to bury Nakasa at Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, near where the assassinated Malcom X had been laid to rest few months earlier. At the time of his death, Nakasa was working on Makeba’s biography.

Nearly 30 years later, Nakasa’s plight stirred journalists back home. In 1993, an article by an Afrikaans newspaper journalist, Dana Snyman, pressured Harvard University to put a modest headstone on his grave. Five years later, the South African National Editors’ Forum inaugurated the Nat Nakasa Award for brave journalists.

In 2012, Kgositsile joined a South African delegation, including Siphiwo Mahala, the Deputy Director in the Department of Arts and Culture, and Vusi Shongwe, a KwaZulu-Natal provincial representative, to negotiate the return of Nakasa’s remains from New York. It took two years and went to the Supreme Court.

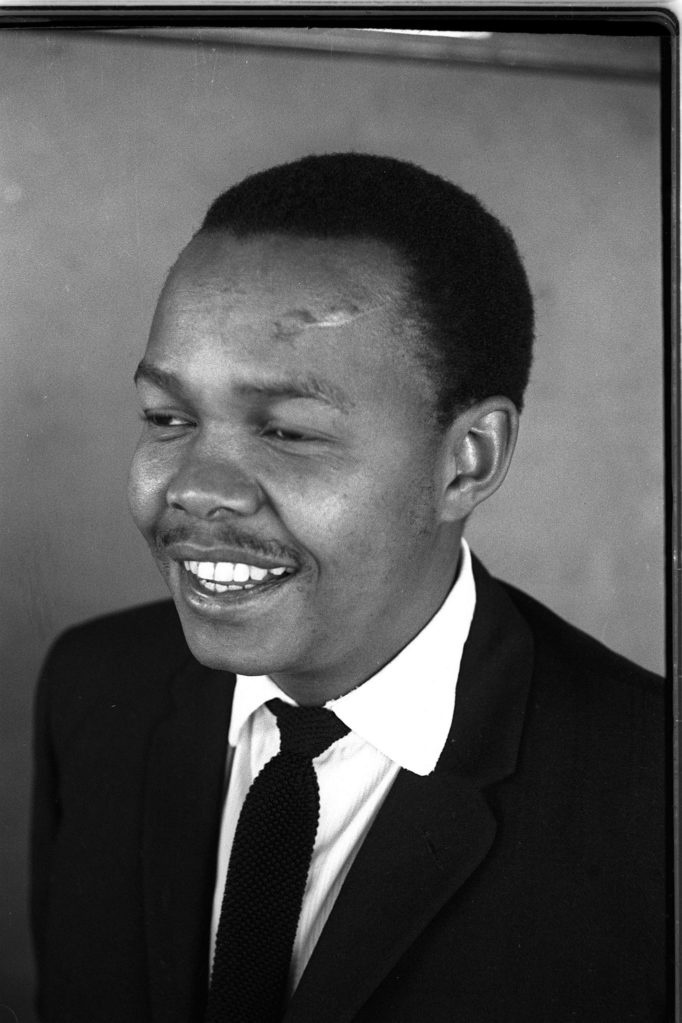

It was a sad end to what could have been a hopeful story for African journalism. A reminder of this hope is a picture of a young African in the front row of a Harvard scholars’ group, dressed in a tweed jacket buttoned over a thin striped tie. The context makes it even more intriguing. In 1964, America was a staid and conservative place. It was a time when many black people lived in fear of being lynched. A year before the country elected a Catholic, John F. Kennedy, for the first time in nearly 200 years of democracy.

Nakasa, the second of three children, was born in Lusikisiki in the Pondoland region of the Eastern Cape. Poverty forced Nakasa to leave school, without qualification, in 1954. His family moved to Durban where he cut his teeth working for the Ilanga Lase Natal newspaper, in both Zulu and English.

Johannesburg beckoned; Nakasa joined The Post and later Drum magazine and freelanced for international publications. He became part of the iconic Drum team: Henry Nxumalo, Casey Motsitsi, Can Themba and Lewis Nkosi.

Nakasa also became the first black columnist on The Rand Daily Mail,

a white liberal newspaper

in Johannesburg.

As Drum magazine struggled against growing press restrictions, Nakasa met John Thompson, an American who led the Fairfield Foundation, an organization supporting international cultural endeavors, at one of the mixed-race parties that Nakasa frequented. Thompson convinced Nakasa to found the first black-owned literary journal, The Classic, in 1963. Later, Thompson encouraged Nakasa to enrol at Harvard.

In another world, Nakasa would have returned to Africa as an erudite professor to enrich and train his fellow journalists; sadly, he didn’t.