It was déjà vu for South Africa’s African Bank Limited (ABIL) when it was put under curatorship on August 10. It was for the very same reason too, liquidity. The Chief Executive Officer and co-founder, Leon Kirkinis, resigned with immediate effect in August. This marks the third time the bank finds itself in trouble.

ABIL was founded by the National African Chamber of Commerce and Industry (NAFCOC) as a black-owned bank that could fund black-owned businesses during apartheid. The first branch opened in 1965 in Ga-Rankuwa, a small township outside of Pretoria.

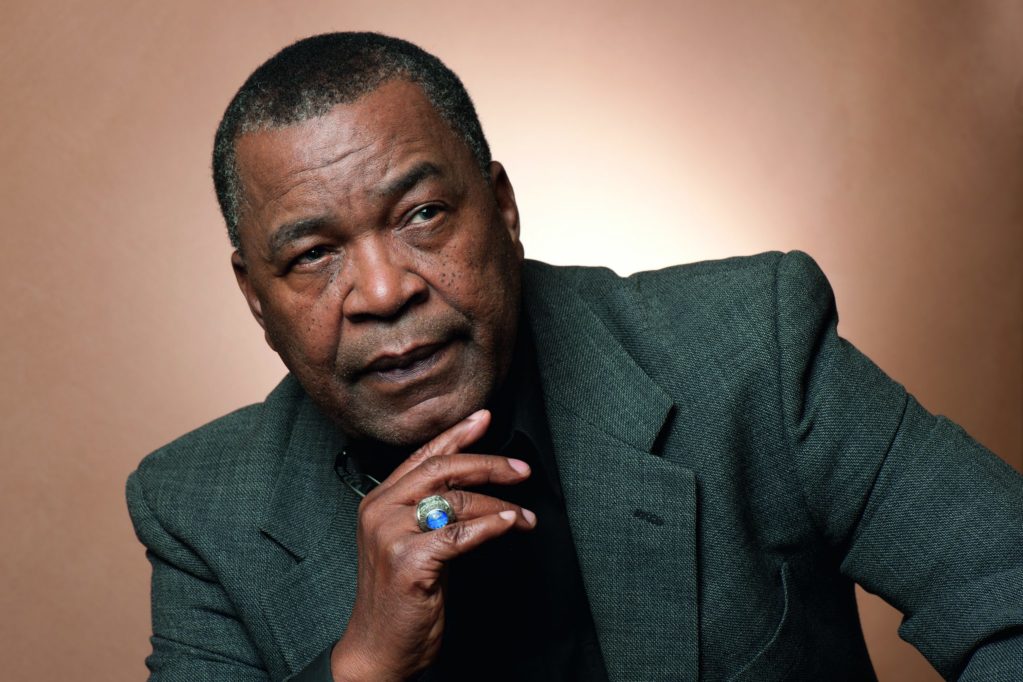

A man that knows ABIL better than most is Gaby Magomola, currently the Executive Chairman of Thamaga Investment Holdings. A veteran of the ruling party, the ANC, and former Robben Island prisoner, Magomola was recruited in 1979 by Citibank, in New York, where he was trained to become an international banker and eventually grew to become its second black manager.

When he returned to South Africa, Magomola was driven by the desire to promote commerce as a career for people of color, as well as create a platform to assist small businesses and entrepreneurs.

From 1986 to 1989, ABIL was placed in curatorship for the first time. In 1987, Magomola joined ABIL after three offers from the bank. He says the bank had a relatively good business model at the time.

The reserve bank persuaded the four big banks, at the time, to purchase preference shares to rescue ABIL.

After proving its worth and getting out of curatorship, Magomola was thrown out of the African Bank by the board because of a business model he’d been working on for the bank. This model is now commonly used nearly 30 years later.

The downfall of ABIL played itself out in public when the bank announced an $800-million financial gap. Trading on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange was suspended after investors began dumping shares and its credit rating was downgraded.

The troubles at ABIL have affected South Africa’s banking industry. Soon after the news broke on ABIL, Capitec Bank was downgraded two levels and placed on review. The top four banks, Standard Bank, Absa, First National Bank and Nedbank, were prematurely later downgraded a level. The downgrading of these top lenders could very well lead to the downgrading of the country’s sovereign rating.

“Effective policy includes the resolution of financial firms in trouble in a way that imposes losses on those investors who profited from that firm’s activities and who were in a position to exercise influence over that firm’s management,” said South Africa’s Minister of Finance, Nhlanhla Nene, at the Southern African Internal Audit Conference.

The Governor of the South African Reserve Bank, Gill Marcus, said that a substantial portion of the non- and under-performing assets and high-risk loans will be bought from ABIL, separating them from the good book, which has a book value of $2.4 billion after impairments.

A $938-million recapitalization is also on the cards.

ABIL’s curatorship does not interfere with the bank’s day-to-day running. Customers’ deposits are guaranteed and loans remain legally binding.

The bank says its vision is to improve its customers’ quality of life through affordable, convenient and responsible credit. It also says customers will always receive the necessary information to understand what they are committing to.

“The unfortunate thing [about ABIL] is that it threw people into a perpetual debt trap… it was an accident waiting to happen,” says Magomola.

In 2013, branches in KwaZulu-Natal were fined $1.8 million for breaching the National Credit Act. ABIL wrote-off loans, removed blacklistings and rescinded court judgements against borrowers.

Although insecure lending leads to an increase in retail sales, it also leads to an increase in household debt. It’s a bad way to finance the economy. Increased limitations on lending will result in a decline in retail sales and manufacturing. South Africa’s inflation was sitting at 6.3% in August.

Magomola believes the bank needs to revert to being a deposit-taking institution that encourages saving and use those savings to make loans where they are merited.

One long standing and loyal customer is Malesela Maraba, a resident of Seshego, a town in the province of Limpopo. Maraba was a member of the Azanian People’s Organisation (Azapo), one of the radical political parties during apartheid. He and his wife were asleep in their four-bedroom house when it was petrol bombed by the police in the early hours of 27 March, 1986.

“It was around 4AM and I was with my wife. When we came out, the police wanted to throw me into the burning house. The idea was to get me killed,” says Maraba.

It is a heavy price to pay for protesting for freedom. However, he survived to see another day.

The fire gutted the house. Maraba took the case to court but without success. He was never paid a cent for the damages. A few years later, he decided to rebuild the house at the very same location.

Maraba says he approached other banks which wouldn’t give him a

good deal.

“Then I heard about African Bank. A friend of mine told me about his friend, Jack Monyepao, who worked there. He told me I must discuss with Jack and he won’t give me a problem,” says Maraba.

At African Bank, Maraba delivered the building plans. The bank also requested that he get quotes for all the materials needed for the house. Everything added up to about $4,200 and the loan was approved in just three weeks. The house got rebuilt with 11 rooms. Much bigger than the home that was petrol bombed.

Maraba says the bank gave customers cash in the past and people paid back their loans. He says he took seven years to pay back the loan and he took other loans after that.

“That’s the African Bank I knew. We paid back the money on a monthly basis. Now I don’t know how this problem came about,” says the 58-year-old Maraba.

“Banking is about assessing risks and managing those risks,” says Magomola.

Some of the outcry from the public comes from customers becoming over-indebted, with multiple loans in play at ABIL. Greater limitations should have been placed on the level of debt these clients were allowed, but one has to question the reasoning behind racking up numerous loans before paying any off. Are South Africans living beyond their means?

Magomola calls for an investigation into why the regulators allowed the bank to provide unsecured loans.

But what should happen to ABIL? Does it deserve to be saved yet again?

“There is a need in South Africa today for a banking institution held predominantly, and owned predominantly, by black South Africans. I’m not saying that African Bank is necessarily that entity, but there is a huge gap and you cannot have a free nation that governs an economy as sophisticated and as large as South Africa that does not have a bank owned by its own people, the indigenous people,” says Magomola.

It remains to be seen if the people will continue to rally behind this bank.