A blank projector screen hangs in the middle of a room in William V.S. Tubman High School. A handful of expatriates and Liberians mill around, waiting for the film that was scheduled to start rolling over an hour ago. Young women wait expectantly behind a table filled with snacks and baked goods. But most of the yellow plastic chairs are empty.

After plugging and unplugging a jumble of chords and tapping a few computer keys the film begins to play. Restless children and 20 or so adult members of the audience sit as a film titled No More Selections We Want Elections screens. It traces the 2005 elections that saw President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf come to power. The sound is gritty, light streaming through the sheer curtains washes out the image on the screen and the audience is small.

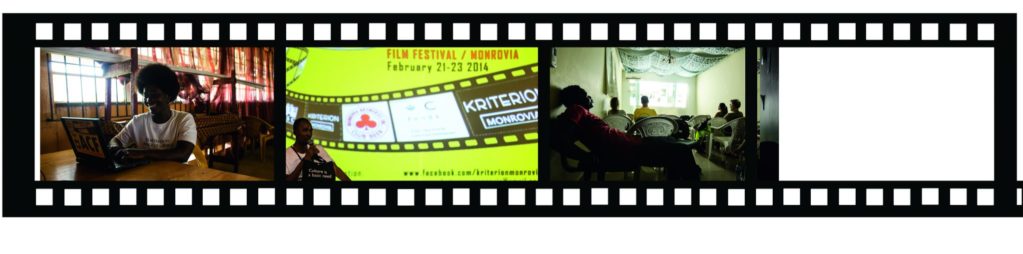

This is the first time Liberia has held a film festival. The brainchild of Pandora Hodge, a young Liberian student, and a collection of her colleagues from the University of Liberia and SPARK, a Dutch NGO that fosters entrepreneurship in post-conflict countries. The Image of Liberia film festival was held over three days in Monrovia in February and aired Liberian and African films in classrooms and communities throughout the city. Some screenings were packed and went off without a hitch; others ran late and attracted a sparse audience.

Through the festival, Hodge and her team hope to challenge the war-torn image of Liberia and build up interest in the art house cinema called Kriterion that she and her colleagues are trying to establish. Films about Liberia’s brutal recent history – it’s civil unrest that spanned three decades, killed 250,000 people and destroyed the nation’s infrastructure – are notably absent from the program that is filled with a small selection of Liberian and African films.

“We are creating a platform where young people can go to express themselves. A cinema is a really good way to get people involved and get people aware of what is happening in the country and abroad,” says Hodge.

Inspired by the model of a cinema that was created in Amsterdam by university students involved in the anti-Nazi resistance movement in the aftermath of World War II, Hodge hopes that Monrovia’s own Kriterion can provide part-time employment to students and also become a hub for Liberian cinema and intellectual debate. The Kriterion model has also been adopted by students in post-conflict cities like Sarajevo.

But, establishing an art house cinema will be a challenge in a country where most people get their slice of cinema in ramshackle video clubs, sitting on wooden benches watching Nigerian, American and Indian films off eerie television screens that sit small in the darkness. In Monrovia, cinemas are virtually non-existent – two of the three cinemas, remembered fondly by Liberia’s pre-war generation, have been demolished. Only Rivoli, a cinema in downtown Monrovia, is still standing and seems to screen Bollywood movies exclusively. These cinemas aired mainly American movies as films were largely limited to government public relations and propaganda. But Hodge and her team, through surveying and research, found Liberian audiences want to see more locally produced films.

Unlike some of its neighbors in the region, like Nigeria and Ghana, Liberia has never had a vibrant film culture. Liberia’s cinema scene is small and amateurish with only a handful of directors producing quality films.

Derick Snyder, a filmmaker and producer, describes most Liberian films as birthday party quality.

“You got a little camera for your daughter’s birthday and you just film the yard. We’ve still got a lot to learn,” he says.

Snyder is one of a handful of Liberian producers who are able to shoot and edit quality films. Most actors are untrained and perform for free; those with talent and ambition head to Nigeria, Ghana or Gambia. Lack of access to equipment, technical know-how and stale plotlines, have hindered the growth of Liberia’s small film industry, says Snyder.

“Everyone is doing ma, pa, daughter crying in the living room love stories,” he says, adding that Liberians prefer the drama and slick effects of many of the Nigerian films.

Snyder, like many producers, has a day job shooting events for the United Nations Mission in Liberia and produces films on the side. He says most filmmakers struggle to earn a living.

Unlike other African countries, the Liberian government provides limited funding for the arts.

But, over the past year, there have been efforts to develop filmmaking by organizations such as Accountability Lab, an NGO focused on funding small projects that encourage accountability. Nigerian-Liberian director Divine Key Anderson heads a part-time film school that helps train students to make short films focused on accountability issues.

“Since 1847, we have been writing papers and not much has changed in this country and that is because 70 percent of our population are illiterate… but with film even a blind man can see,” says Anderson, who, like Hodge, agrees that film can be instrumental in creating political debate and change.

For James Emmanuel Roberts, who made No More Selections We Want Elections, the arts play a vital role in creating national identity and broader political and social debate. Roberts, 70, headed the national cultural troupe in the 1970s and helped create a satire television series called Kotati, meaning ‘sit down there’ in the Kru language, that aired on Liberian state-run television.

Roberts argues the development of a film scene in Liberia will play an important role in creating a collective historical memory that was largely erased by the 1980 coup and civil war, during which many records and archives were destroyed. He says that cinema could help Liberians shape the story of their nation, whose recent history has been narrated by outsiders, namely Western journalists. Roberts and his son are currently working on a film on the 2011 elections.

After I finish interviewing Roberts, the public electricity cuts out and Hodge and her team rush to fuel up a generator for the next screening.

Creating an art house cinema, in a country whose cultural scene is only just beginning to re-emerge a decade after the civil war, will be a challenge. Hodge is confident she and her Kriterions are up to the task and that the film festival will continue to attract a culture-hungry audience.