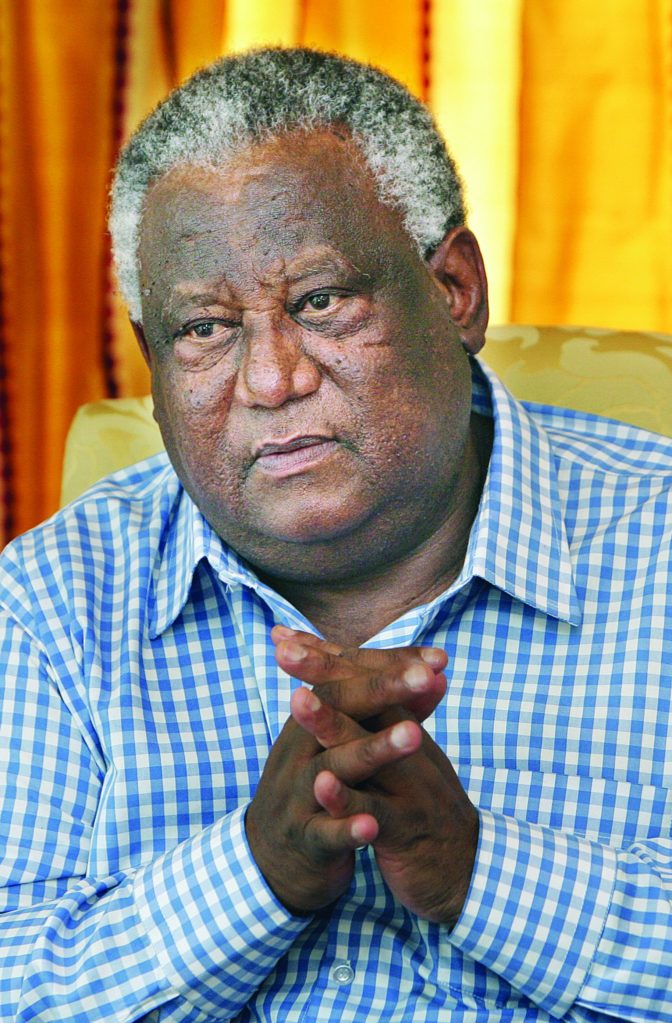

“Is there anything that you haven’t done, that you’d still love to do?” I asked Zwelakhe Sisulu towards the end of the interview.

After a deep sigh, he pointedly and regrettably replied, in his trademark baritone voice, “The reason I got into journalism was because of my love for writing. Then I was diverted. I never did what was my first love. I hope that one day I’ll get a farm in some remote area, age gracefully and write.”

Well, it was not to be.

Just over a month later, death would put paid to that wish along with the hope of the journalist who was interviewing him.

On Thursday October 4, I was chairing a public discussion in East London, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape when, the Managing Editor of FORBES AFRICA, Chris Bishop, sent me a text message saying that Zwelakhe Sisulu had died.

It was barely a week after we had published, as part of our October issue, a nine-page focus on the increasingly volatile mining industry in South Africa. Five of the nine pages focused on the chaos in the platinum sector, while the other four were dedicated to manganese mining, looking at whether new players like Kudumane Manganese, of which Sisulu was chairman, were doing anything different to avert the crisis that the platinum sector was experiencing.

Sisulu’s encounters, and views, were the thread that held together the manganese article. Chris and I had subsequently spoken about going back to Sisulu, with the hope of possibly getting him to grace the cover of one of our future issues. The leftovers from my interview would form a good basis from which we could build a really strong lead story about the rise and rise of a journalist-turned-entrepreneur, who had so excitedly told me, “There’s nothing as exciting as being an African in Africa today”.

I knew that it would be one of the easiest stories I would ever be able to tell, for Sisulu himself was the master story teller. Like a good journalist, he had the amazing ability to tell so much, so well, in so few words. When, for example, I asked who had inspired him the most in his life, he gave a simple yet sophisticated reply, “It’s difficult to say, but the man I admired greatly was Oliver Tambo. He’s somebody who stood head and shoulders above everybody else. Joe Matthews looked through you like a prosecutor. Madiba tapped you with a jab. Oliver Tambo hugged you.”

I immediately got the picture, or rather, the message.

Like his hero Tambo—the man who held together South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC) for decades in exile, while other leaders like Mandela were in prison—Sisulu appeared soft, yet his intellect was so sharp, his organizational skills impeccable and his determination steely.

Never the one to shy away from new challenges, in July 1978, a mere three years after kicking off his journalism career as a cadet reporter and merely 28 years old, Sisulu was elected president of the newly founded Media Workers’ Association of South Africa; the same year he was appointed news editor of the Sunday Post.

Two years later, he would lead the longest and biggest strike by media workers in the country, ending in successful wage negotiations, albeit the authorities would retaliate by forcing the proprietors of the newspaper he worked for, The Post, to close down.

As if that was not enough, Sisulu—alongside fellow journalists who had led the strike—would be banned for three years, placed under house arrest and would not be allowed to work as a journalist, attend public meetings or even go to townships other than the one in which he lived.

Following the lapse of his banning orders in 1983, Sisulu would get a Nieman Fellowship, a mid-career journalism award entitling him to a year’s study at Harvard University. And it was during this time, sitting among the audience listening to a speech by his hero, that he would not only rekindle his childhood memories of how warm Tambo was, but find other good reasons for admiring him.

“Oliver Tambo stood up and spoke. There isn’t a speech in the world that has made more of an impression on me than that one. The thing about that man was the way he would marshal his facts and use them as galloping horses. He was quite unequalled. I had always thought of the struggle in emotional terms. But when Tambo spoke I understood, for the first time, that there was actually a rational contestation, that it wasn’t just Amandla! Amandla!” recalled Sisulu.

On his return to South Africa in 1985, Sisulu was appointed editor of The New Nation, a new weekly publication sponsored by the Southern African Catholics Bishops’ Conference, one that, in more ways than the publications he had previously worked for, would become a bigger thorn on the side of apartheid’s apologists. Needless to say that more bannings, gagging orders and imprisonment would follow.

When Mandela was released from prison in 1990, Sisulu became his press and private secretary, traveling the world with the revered statesman.

“No one would see Madiba if I didn’t want them to see him. The question rose to me very fundamentally when I was working for Madiba, do I want to be a gatekeeper all of my life?”

Following the historic 1994 democratic elections, after which Mandela was elected South Africa’s first black president, Sisulu was deployed by the ANC-led government to the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), the national public broadcaster, as its first black Group CEO, a position he would hold until 1997.

After leaving the SABC he would become a businessman, with stakes in a string of companies that straddle mining, energy, telecommunication and the media.

As more messages came through to my cellphone on that fateful day, from, among others, board members of a community television station that I chair and which Sisulu’s broadcasting outfit generously supports through funding, equipment and training, and as tributes continued to appear on social media sites from fellow journalists—who either worked with him or who were inspired by his activism as a journalist—my mind raced back to our encounter a

month earlier.

From the bits he had told me about the years he had spent outside the limelight focusing on building his business empire, I could not help but be in awe of the kind of model entrepreneur he had become, in a continent so desperately in need of them. He told me the story of how he was working with government of São Tomé and some Chinese business people. The terms were that the São Toméan government wouldn’t pay a dime, but after 18 years would own

the station.

Brutally frank, as he was kind, provocative even, he sneered at ongoing suggestions for the nationalization of mines in South Africa. Not surprising for a mining magnate, I pointed out to him during our interview, but he insisted his reasons were more practical than ideological. He cited as examples telecommunications utility Telkom as well as the SABC.

“The major challenge facing this country is the management of public assets. Until and unless we perfect management of public assets, we must not even talk of nationalization.”

Not far from the auditorium, from where I had just received the news of his premature death, was the state of the art minerals polishing factory Sisulu had urged me to visit. Based at the East London Industrial Development Zone, the factory was very special to him, he told me. He was passionate about the project because it was, in part, his way of giving back to the Eastern Cape, the largely impoverished province that gave birth to both his parents, struggle stalwarts Walter and Albertina Sisulu, as well as other outstanding South African liberation heroes like Steve Biko, Mandela and Tambo.