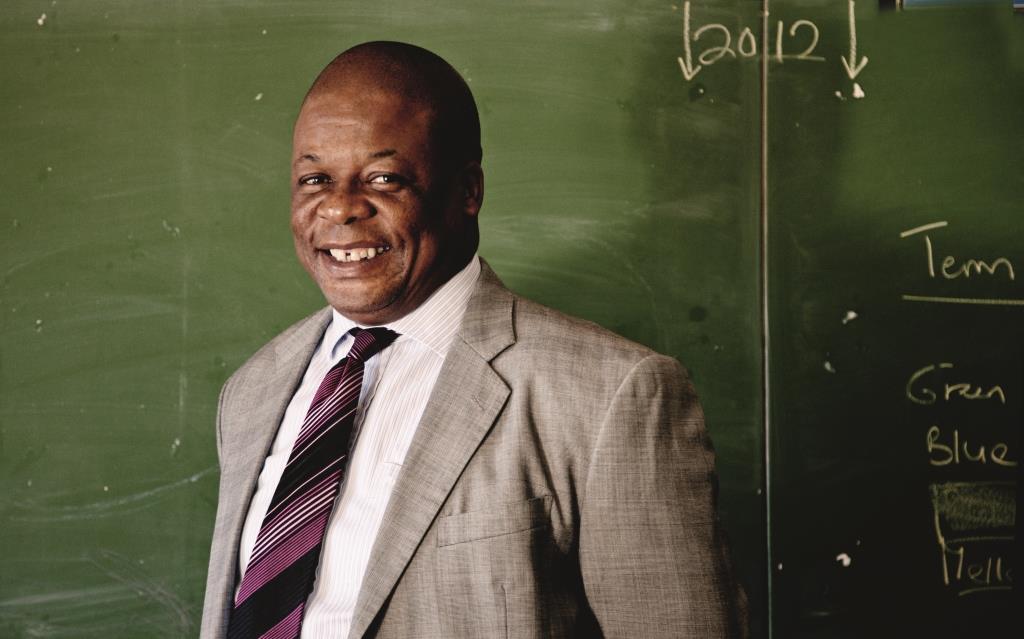

The year was 1994. South Africa’s political climate was changing; a new president promised democracy and opportunities for all. For Romeo Makhubela life was just beginning. After years of teaching, he decided to register at business school. He put down the chalk and left the classroom, and today he is the CEO of a 100 percent black-owned investment company, a world away from high school teaching.

This epiphany turned him into one of the country’s emerging financial services providers. The reason Makhubela was in the classroom in the first place was no surprise. For most black South Africans at the time, that was the highest you could reach. You could either be a policeman, nurse or teacher.

It wasn’t that he didn’t like teaching. He had studied for a Bachelor of Commerce degree and topped it with a teaching diploma, which led him to become a commerce teacher for final year students, in the North West province of South Africa.

“The most exciting part as a teacher, especially a high school teacher, is when the [matric] results come out, and you realize that the investment that you made [has paid off]. I remember one year ‘I’ had a lot of distinctions and for me that was so fulfilling because you could see people going to university, some are now working and you know that you were part of that product,” says Makhubela.

“I started teaching in 1990… Around 1992 or ’93 I started noticing that a change was coming in South Africa and clearly businesses would start transforming and there would be huge opportunities, especially for people who had a Bachelor of Commerce qualifications,” says Makhubela.

It was never easy, amid the political turmoil of his country. During his university studies, Makhubela was also politically active.

“I matriculated in 1983. Things were quite tough at that stage; I think the upheavals were starting… It was terrible in those days and I had [to take] a break in ’84, then in ’85 I started doing my Bachelor of Commerce degree ’till around ’88. There was one year where we didn’t write exams because of the [political] problems.”

“Politics then was something that you just couldn’t avoid because there were a lot of injustices in this country… Especially at [university] because you started seeing the world and seeing that certain things weren’t correct… The way some lecturers conducted themselves, I can tell you one example; [In our first year] the one [lecturer]… just came and said ‘Look this is such a big class, I’m not used to teaching [so many people] and I can assure you that in third year 80 to 90% [of you] will be gone’. And you sit down and say ‘How could you make such a statement?’.”

Today, he is no longer in politics; he sits at the head of Vunani Limited. The eight-year-old company was launched in 2004 following a management buyout from African Harvest. In 2007, the company listed on the JSE AltX Exchange raising R175 million ($21.4 million). They currently have offices in Johannesburg and Cape Town, in South Africa and Harare, Zimbabwe.

He worked his way to the top, starting out at an insurance company as a graduate trainee, then he became a financial analyst for an asset management company and after around six years in the asset management field, he was recruited as chief investment officer for a life insurance company. And now he is heading Vunani Limited, an emerging company that wants to leave its mark as South Africa’s leading black-owned financial services provider. Vunani Limited is listed on the JSEAltX; it is currently listed 19th in the financial services sector, with R204.5 million ($24.96 million) of market capitalization. The company has a diverse portfolio, which consists of Vunani Fund Managers; Vunani Capital; Vunani Technology Ventures; Vunani Securities; Vunani Capital Markets and Vunani Properties. Now it is going up against the best in the financial services industry and is forging its own way. One challenge they, like many other companies, are facing is growing the industry.

Makhubela’s focus now is on getting his countrymen to start putting away more for a rainy day.

“One of the biggest gripes about South Africa is that if you look at our saving ratio, it’s quite low and clearly that tells to the culture or the environment from which people [come from]. My sense is that, maybe in the white culture it’s much better because at least that kind of information was instilled but in the broader black community… the kind of savings that you generally see within [them] would be pension funds, which is forced, because when you work you get your pension fund automatically.”

Last year, South Africa’s minister of finance, Pravin Gordhan, said that South Africa’s savings rate was low and that it “needed to increase its saving rate if it were to become the ‘China of Africa’”.

Makhubela agrees.

“Savings are critical… look at the Chinese for example. The savings rate there is extremely high—but you could argue that it’s influenced by a number of facts because they don’t have a proper social system… But that helps because if you look at the global crisis we are experiencing now… the Chinese have played an important role in terms of lessening the impact of the global crisis because of their savings.”

According to The South African Savings Institute (SASI), South Africa is the lowest ranking member of BRICS when it comes to saving.

“The International Monetary Fund (IMF) statistics show that since 2001, compared with its BRICS counterparts, SA’s rate of national savings has remained flat… In China, gross savings are over 50% of GDP, in Russia 30% and Brazil over 18%. In South Africa that figure is about 16.5%… It’s 72nd in the world behind Algeria (3rd), Morocco (25th), Nigeria (27th), Zambia (32nd), Namibia (34th), Botswana (42nd) and Lesotho (62nd)”.

The poor argue that saving is the last thing on your mind when you are living from hand-to-mouth, while the middle class chooses to splash out, so where does that leave the future of the fund management industry?

Makhubela says that when the rate of unemployment decreases, and more people start earning and being forced to save, then the tide will change. But while there is no growth in savings right now, Makhubela and his team are looking beyond borders, with Zimbabwe under their belt, they are also currently setting up in Namibia.

From marking exam papers to signing off millions, Makhubela is trying to teach one of the greatest lessons in life—how to save even when it hurts.