Jonathan Liebmann is 29, owns 25 buildings and has lived on five of the seven continents. Now, he has made his nest in a small corner on the east side of the most vibrant city in Africa—Johannesburg.

Johannesburg city was established in 1886, as a farm where gold miners from all over the globe came to make their money. That is where it got the name Egoli—meaning place of gold. In decades to follow, it became the shopping mecca of Gauteng’s elite. Today, all the big banks and businesses have relocated to the northern suburbs and the new tenants are mostly African immigrants looking for a place to make a living; the streets are busy, there are shops at every turn and a multitude of languages in the CBD.

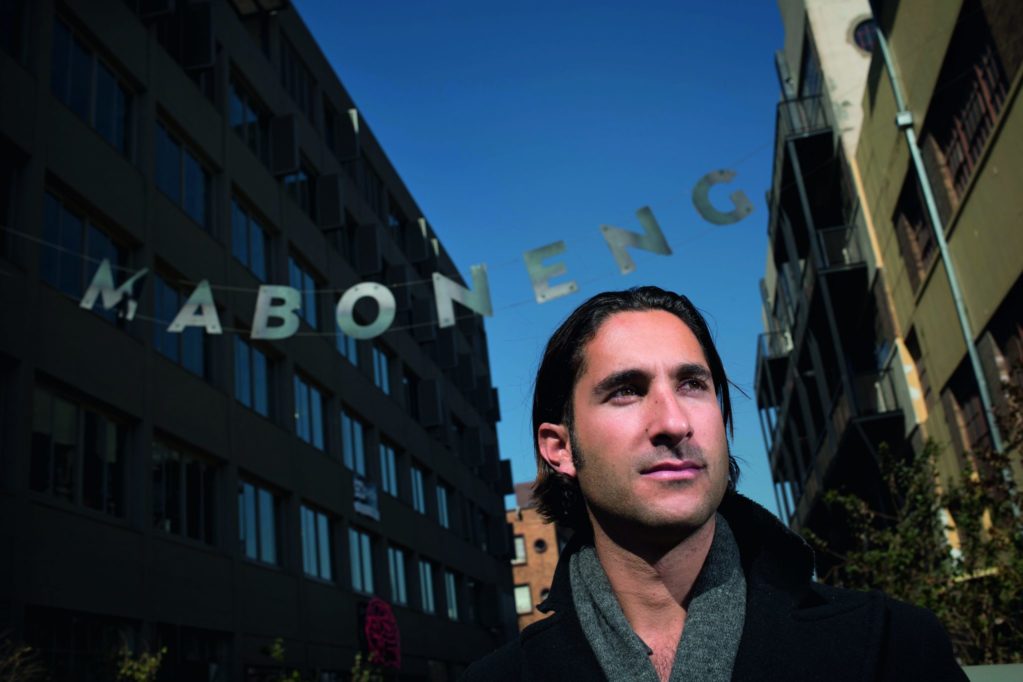

There is a sign that hangs between two buildings on his street, it reads Maboneng— meaning place of lights in Sesotho. It’s a fitting description for a beacon in the middle of a city plagued by crime, dilapidated buildings and grim life. Just down the road, there’s a men’s hostel where even the police are afraid to go.

Liebmann is rejuvenating the east’s run down image one building at a time. The corner coffee shops, restaurants, independent movie house and boutique hotel are abuzz as you walk the streets of Maboneng Precinct.

He has just bought his 25th building, which he will convert into apartments. We stand on the roof of the new building looking down onto another flat roof. Two recycling vendors are having lunch on a two plate stove, they are surrounded by recycled bags containing plastic bottles. This is one of the many facets of Johannesburg hustle.

You could say the streets behind Liebmann are a playground for his entrepreneurial mind.

Property developer Jonathan Liebmann, Johannesburg; 19 July 2012 – Photo by Brett Eloff.

Liebmann’s entrepreneurial spirit is as young as many of the buildings are old. He made his first profit at 18, at a time when most people hadn’t even thought about buying their first car, let alone buy one. He had bought, renovated and resold an apartment and at 21 he turned an old factory into an office for rent.

“When I was 18, I realized I wanted to be involved in property. I went to university but while I was [there] I started investing in property on a small level. I bought my first apartment that I renovated, with the bank’s money, and then I just worked my way up from there… I enjoy being the pioneer and taking the first steps, so for me that risk was an attraction. And at the same time I was completing my accounting degree so I was working and studying as well,” says Liebmann.

Liebmann bought his own apartment at 20, after a year of nomadic life across the world, traveling and doing odd jobs from construction to telesales consulting. Traveling is something he learnt from a young age, as a child Liebmann moved almost ten times with his divorced single mother and older brother.

“I started thinking about how I could do my own large developments of [loft culture] and started looking for old factory spaces that would have the right type of aesthetic to do that and that’s when I found my first buildings in Maboneng.”

“I traveled all around the world after school and that exposed me to a lot to urban culture,” he says.

And since his return to Johannesburg—the city of his birth—he wants to inject new life into the city; artists, business and residents are following him.

While on his travels, Liebmann went from being a construction worker to a telesales person, skills he would later use in his chosen career.

You can tell from the moment you meet Liebmann that he’s driven. He’s sharp and has an air of confidence that could be interpreted as arrogance when he speaks about his work. He’s got that ‘I know what I want and I know how I’m going to get it’ tone as he tucks his brown hair beneath his ears throughout the interview.

Earlier this year, Liebmann was invited to the World Economic Forum in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

“I was selected as a global shaper along with 30 other young people from Africa. I learnt about the common objectives of African countries to collaborate with one another in an attempt for Africa to become the next frontier,” says Liebmann.

While we sit at a corner coffee shop, a number of people greet him as they pass by. Liebmann and his vision are growing in stature in this area of decaying factories and empty buildings, which is a living manifestation of the saying “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure”.

Not only has it managed to attract people and money back into the city but it has also put his family back together.

His mother owns a coffee shop, his father owns a gallery and his step-brother works here too.

It’s a risky investment.

One minute one area could be the trendy spot where the masses flock and in a number of years may degenerate and experience flight.

His architect, Enrico Daffonchio says property goes in cycles in every city of the globe.

“There is a spectrum of different perspective [on its potential], however the spectrum of opinion from the cynics is reducing… Cities get renewed throughout history, it’s not a new thing. There are tax incentives to refurbish those areas. [So] there’s tax incentives and governments copy each other ,” says Daffonchio.

How did Liebmann get people to Maboneng and does he think they will stay?

“I think initially the challenge was changing people’s perceptions of the city. Yes, it’s a continuing struggle but it’s far easier as we grow block by block… I think Johannesburg is at the beginning of its curve of regeneration. There’s a long way to go [but] it’s certainly showing promise… You’ve got to build spaces that attract people back…”

Property economist and University of Capet Town lecturer, François Viruly says it’s not the government’s duty to upkeep the city.

“The role of government is primarily to ensure that an environment is created that encourages private sector investment in the CBD… I don’t think that there is anything wrong with the private sector owning buildings in the CBD. Urban decay is a problem that local governments have faced across the world. In South Africa, the decentralization of commercial space has invariably left CBDs with high vacancy rates.”

These are vacancy rates which Liebmann is grabbing with both hands—a dream he is creating one building at a time.