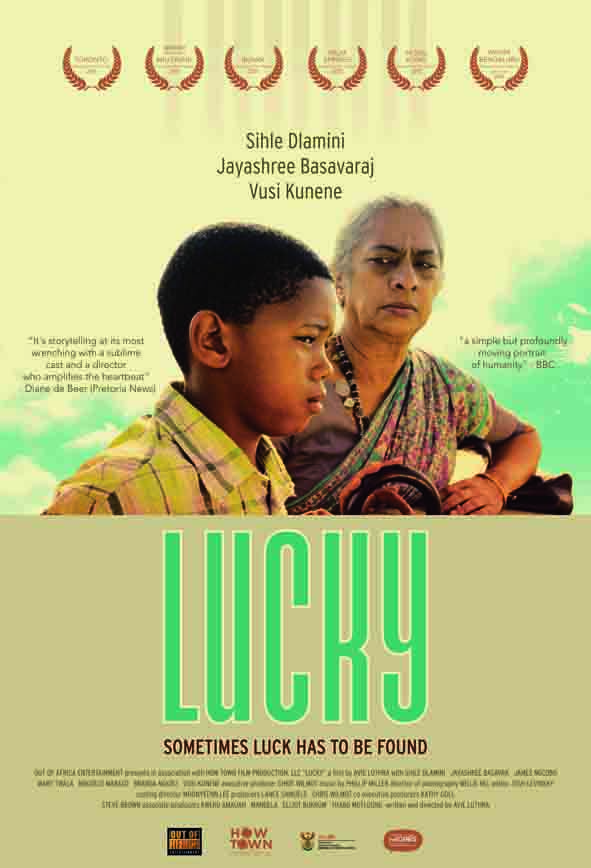

I will go to school and study hard. I’ll be a success. I promise mama,” vows 10-year-old Lucky, at his mother’s grave. Lucky (Sihle Dlamini) gathers his few belongings, and like so many other South Africans leaves his rural Zulu village to the city.

Lucky (2011) is a poignant depiction of contemporary South African society and its problems. It explores the complex cross-cultural and racial relationships. It steers away from well-worn depictions of relations between black and white South Africans as depicted in archetypal post-apartheid South African films. The film explores the rainbow nation through relations between black and Indian South Africans. The film is in Zulu and Hindi with English subtitles.

Lucky’s arrival in the city is overshadowed by his uncle, Jabulani, (James Ngcobo) who has spent the schooling money—from the boy’s mother—on alcohol and women. He hands the boy an audio cassette with a final message from his mother. Jabulani says the youngster should make himself useful by finding a job instead. The boy sleeps hungry on the doorstep.

The film tracks the relationship between Lucky and Padma (Jayashree Basavaraj) who lives in the same building as Jabulani. She is his only hope of listening to the audio cassette. The Brahminic Indian widow, receives him with caution. She does not disguise her racial prejudices when she handles the audio cassette with a cloth and uses her walking stick to prod Lucky. The boy sleeps on her balcony, behind locked doors and drawn curtains, in a manner adopted by many South Africans in the face of poverty and guilt; Lucky is shut ‘out of sight, out of mind’.

Padma cares for the boy, but what seems to be a sudden change of heart, is actually a façade to receive a R200 government grant allocated for AIDS orphans. In return for cleaning her house, she sends him to school.

Together they undertake an emotional journey to Lucky’s village to escape from his neglectful uncle. Here they are met with the deeply-ingrained stigmas associated with AIDS, the disease which took Lucky’s mother. “Mother told me not to share food with you because you will spread the disease,” he is told by a girl from his village. Together with Padma, he goes in search of Dumisani (Vusi Kunene), a man who was believed to be dead and who might be his father. Dumisani, a funeral singer, is a constant reminder that in the midst of life we encounter death. The musical score, written by Phillip Miller, features African instruments and allows Kunene to explore his musical range.

Over time Padma’s maternal instincts overcome her Brahminic racism when she sells her belongings to help the boy. In a heart-warming scene, their bond transcends the language barrier when they talk about family, over Padma’s open family photo album.

This is award-winning writer and director, Avie Luthra’s, second feature film. It is based on the 2005 short film, by the same name, which won 47 awards. “Improvisation made the scenes and relations between the actors appear real and believable,” he says.

Willie Nel was well cast as the director of photography. The hand-held nature of the cinematography gives the film an authentic feel, allowing for a sense of voyeurism. “We wanted to strike a balance between documenting the story moments, and creating an intimate connection with our characters,” Luthra says. The camera attempts to go unnoticed, it hides behind grass, balconies, window panes and burglar bars. By doing so it simultaneously delineates the divide between characters to illustrate that understanding and compassion are needed for real reconciliation and to break down prejudice.

The film will be released on July 21 in South Africa; and is expected to be released in other parts of Africa in the coming months.