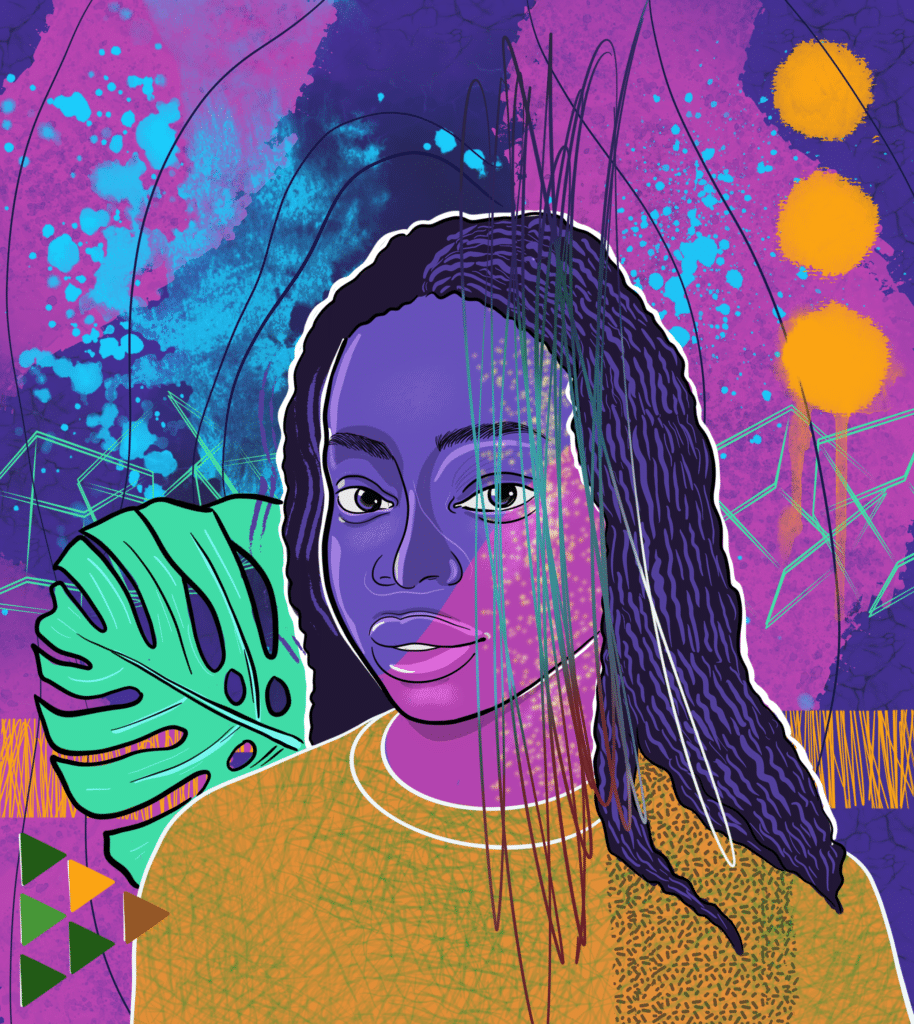

East African techpreneur Neema Iyer works at the intersection of data, design and digital to eventually enable products, policies and programs that take into account the needs of African women.

ARE GENDER DIFFERENCES AS RIFE on the world wide web as in the real world? When technologist Neema Iyer returned home to Africa after graduating from Emory University in the United States with a degree in epidemiology and statistics, she was bent on addressing gender from a technology perspective.

Born to Tanzanian and Indian parents and raised in Nigeria, 34-year-old Iyer is today running Pollicy, a firm she founded in Kampala, Uganda, as a civic technology organization that works at the intersection of data design and technology and understanding how data can be used most effectively for improving service delivery through research, digital literacy, digital security and products.

When she first touched down, she took up a job in Uganda where she worked in the ICT sector, but under predominantly white, male founders from the West. There was also a lack of touch points in governments with the African context. So Iyer decided she needed a fresh perspective using a gender lens.

“When you really look at it like a lot of technology, a lot of data, the systems are developed in Silicon Valley and I don’t feel that African women are particularly the end users when they design different technology,” says Iyer.

Pollicy, funded mostly by grants from big tech like Facebook and Mozilla, more broadly focuses on gendered data and feminist data, that takes into account power dynamics and the person researching.

“If you don’t have this kind of data, then it would be very difficult to make platforms or policies of programs that really take into account the needs of African women and what are the challenges and what are the gaps,” she says.

For instance, field research or product development would usually involve talking to the head of the household or people in authority, which would usually be men. There are many other situations where women may not be allowed to take part in research, and Iyer thinks challenging this status quo is more important now more than ever.

“Women in Africa are least likely to be connected to the internet, so there’s a very big digital gender gap. And they tend to have lower digital literacy, they tend to have lower ownership of mobile devices, they tend to have lower access to information. So, when you take all of these things into account, you can’t just have a one-size-fits-all solution for everyone.” Iyer notes cultural differences in even who can answer a phone call or who can own a phone.

These restrict women’s voices and participation. And even those can be online, as substantiated by online violence and gender disinformation. “It basically leads to the censorship of women, it leads to them leaving online spaces…if you don’t really think about these issues from the gender nuance, then you can replicate a lot of the discrimination that already exists in the physical world.”

For her, these aspects need attention to meet the different needs of people, and to build products accordingly. Iyer is also interested in combining art and data.

“So, moving beyond just spreadsheets and trying to make data more accessible to people.”

For example, her team worked on a project in Uganda called ‘Create Your Kampala’, where they collected data from local communities on different social services, and then worked with them to create wall murals as a way to share back their data and get people involved in the conversation.

“[We wanted to say] ‘you own this data; this is your data; how are you going to use it to improve your situation’?”

But the challenge is that a number of African countries are not moving as quickly as they should in using, supporting and protecting data. Data collection is expensive, there are many administrative hurdles, and it needs a lot of trustbuilding. Pollicy is about four years old and Iyer had hoped it would have made more headway in this time, thinking there would have been be so many competitors in the space by now.

“When I look back, I don’t feel like so much has changed, like we’re still very much lagging in the conversations. A lot of the artificial intelligence conversations are dominated way more by other countries, and even though funders are trying to do more in the African context, there is just not enough happening. So, I would love to see more organizations coming out and doing much, much more work on everything from collecting data, to analyzing it, to processing it, to getting value from it… with a feminist lens.”

Iyer asserts that data will really help drive innovation and improve services, because if people know where the gaps are, then they can improve business, creativity and products. There is, of course, the fear that governments could use these systems to oppress dissenting voices.

“Everything we do is grounded in ethics and equity and inclusiveness, so that when you do build technology, it’s not used to harm marginalized people… we need to come together now to think about that and to come up with solutions… I feel like there’s this urgency that we need to come up with better laws that work for everyone.”

Another challenge Iyer notes is the need to make data as intersectional as possible.

“You don’t want power to be concentrated… so really thinking about power dynamics when you use data, I think it’s that intersectionality of gender and class and tribe and ethnicity, so that you can really make equitable products from the data.”

Iyer also hopes to expand beyond Africa’s borders and continue working with government and civil society to create a better world. “You know, crafting our futures together in a way that works for everyone; that’s equitable and that’s inclusive and we want to make our own decisions for ourselves; so I really want to push that narrative.”

BY INAARA GANGJI