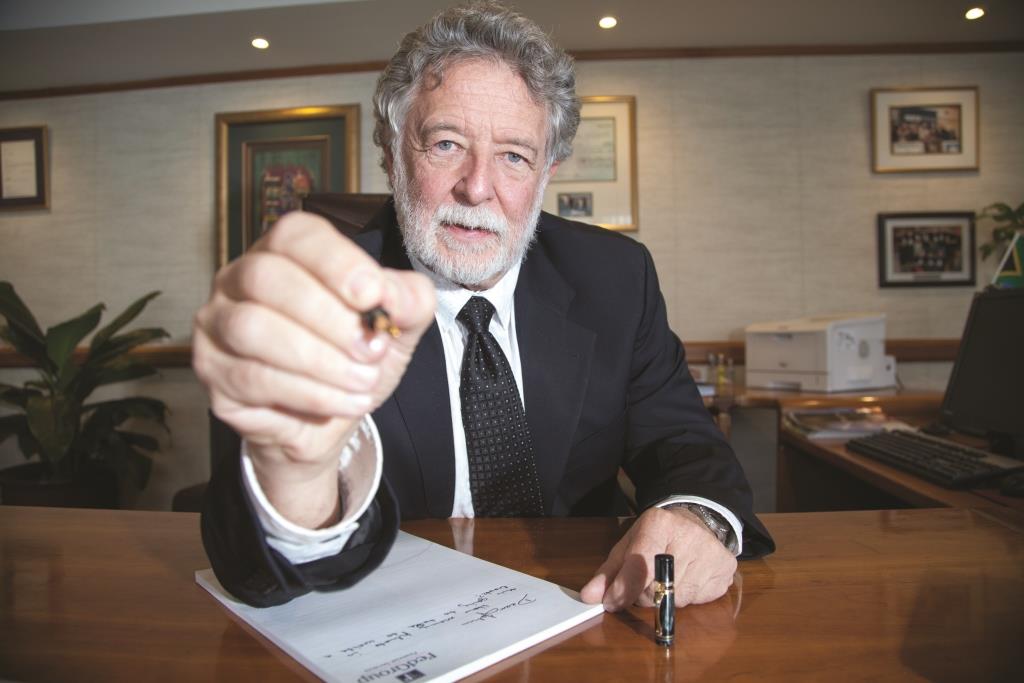

It was a hot summer’s day, just after midday in November 2003. John Field was sitting at his office in the wealthy suburb of Sandton, South Africa, when the phone rang.

“The Scorpions are coming!” said a colleague from Investec.

The Scorpions were the country’s feared anti-corruption investigative unit, now known as the Hawks. The word was that the Scorpions were coming not only to raid his company, FedGroup Holdings, but to close its doors.

The Scorpions never came, but it triggered years of turmoil. They left FedGroup to the Financial Services Board (FSB)—the regulator for the financial service industry.

“It was four years, but that first day was terrible. It’s hard to actually put it into words,” says Field.

The writing had been on the wall a week before. Field had received a letter from FSB saying it had found irregularities in his participation bond company, FedBond—a subsidiary of FedGroup Holdings, a family-owned investment and trust company.

If the Scorpions or FSB closed down FedGroup, Field would lose everything he had built since 1990. He founded the company; a participation bond company, FedBond and later FedTrust, which dealt in trusts, wills and estates. His investors, including around 10,000 pensioners, stood to lose everything.

It was a sorry chapter in a company Field had been working towards since 1984. In that year, he applied for a participation bond license from FSB, but it took six years, longer than he had expected. In 1989, Field bought the smallest participation bond scheme in the country at the time, Haley’s Trust—later renamed FedBond—for R100,000 ($39,000). It was the simplest way he could get a license to manage his own company. He registered the bonds at R340,000 ($133,700) and grew the investment to R1.6 billion ($271.6 million) in 10 years, to become the largest participation bond scheme in the country. A participation bond provides investors with the certainty of capital preservation, coupled with the consistency on interest.

All was going well until the letter from FSB stated that the company should stop receiving new investments. The inspectors from FSB said the company appeared to be cash-strapped and that the scheme did not qualify as a participation mortgage bond scheme.

A few days later, Field and members of his board were summoned for a meeting at FSB’s offices. The FSB registrar told them that, based on a report by inspectors, FedBond was terminally ill and declining in financial soundness. This was mainly because the properties bonded by the scheme were unsound or not generating sufficient income to be able to pay participants their interest and capital payments. FSB said FedBond had a net shortfall of R4.3 million ($584,200) in August 2003. The registrar concluded what the team dreaded: that FSB would apply for curatorship. This is a way of guiding an ailing company back to health, under the stewardship of a new management team.

“To this day I cannot understand what the rationale was to try to close us down. It just did not make sense,” says Field.

Prior to its court appeal in support for curatorship, the FSB had called Field to take over management of around three poorly run participation bond schemes. In every case, not a single investor lost any capital and all continued to receive monthly interest on their investment.

While Field was trying to grapple with how to handle the situation, Investec made an offer to FSB to purchase FedBond out of curatorship.

On December 3, 2003, FedBond was informed of a court application for curatorship. Not knowing his fate, Field withdrew R250,000 ($39,500) from his account to give to his wife and four sons, while preparing for the worst and the possibility of arrest.

The court turned down FSB’s urgent application for curatorship. Field’s lawyer told him that they had agreed on a joint management agreement, whereby a monitor would be appointed to oversee the operations of the company. The judge wanted to give FSB time to prove its claims, by postponing court proceeding to January 2004.

These court proceedings were then postponed to February, when a monitor was appointed. The monitor would look for any reason FedBond should be out of business.

In June 2004, the monitor submitted his first report to the court. It was positive. He recommended that the company be allowed to make capital repayments to its participants. Following this, the FSB registrar submitted an affidavit saying the company would not be able to cope financially and that it should remain under curatorship. The court extended the monitorship to January 2005. The agony for the company would continue, but Field refused to go down without a fight.

January came around, when Field worked on an affidavit with his legal team to apply for dismissal of FSB’s application for curatorship, because he believed there was no good reason for it. Having heard counsel from both parties and read documents submitted, the judge agreed to postpone the application again, to June 2005.

To make matters worse, Investec applied to join FSB’s application for curatorship of FedBond, claiming that it had a R344 million ($60.5 million) stake in Field’s company. When Investec bought out Fedsure, FedBond was one of the subsidiaries, of which Field was sole shareholder. Field had pre-emptive rights to the FedBond shares and Investec reluctantly parted with them. As part of the deal, Investec left the R344 million ($60.5 million) in FedBond as bridging finance to serve as security for non-performing bonds. Field maintained that the funds were never part of the scheme. Investec now claimed it was a participant and should therefore be secured and ranked equally with all the other participants in the scheme.

During the same period, Field became aware that confidential information relating to the company’s business was doing the rounds in the financial sector. A private investigator was called to scan their offices for surveillance equipment. A bugging device was found in Field’s office. He couldn’t find the culprit and had to be careful about what he said in the office.

Following months of negotiations with Investec, a deal was reached in July 2005. Field gave up R150 million ($21.8 million) to Investec. They agreed that it was the end of the bridging finance and also agreed to withdraw their request for FedBond to go under curatorship.

Investec was off his back, the remaining challenge was to get rid of FSB’s application for curatorship.

After numerous bad days, it wasn’t becoming any easier. At every court appearance there seemed to be a postponement. While Field was fighting FSB, his business was suffering. He attended another court hearing in October 2005, but judgment was reserved until December 2005. FSB’s application was dismissed.

Early in 2006, Field’s lawyers requested permission for FedBond to take in new investments from the public, but FSB refused. Without the funds, Field would not be able to make capital repayments.

Following a meeting with Field and FSB, a new monitor was appointed in November of the same year. He would do the same job as his predecessor. The back and forth between FSB and FedBdond would continue for nearly four years, meanwhile FedBond was losing money and clients. Of the 15,000 FedBond participants, 12,000 remained. Around R70 million ($9.3 million) was paid out to those who left.

“We had people ask us for their money. We repaid them and then a week or a month later they put the money back into the scheme. They just wanted to know if we had sufficient money to do that capital repayment. And we did. Every single cent,” says Field.

By June 2007, the company was still unable to accept new funds. Field approached FSB, but without success. Two months later, two weeks before an appearance at the Supreme Court, where an appeal was to be heard, FSB requested a meeting with Field.

FSB was thinking of withdrawing the appeal. It was reported in newspapers that the minister of finance intervened, because it was not in FSB’s interest to continue depleting their budget indefinitely in the pursuit of an application for curatorship that was going nowhere.

Once the dust settled, three months later, FSB granted FedBond permission to take in new funds and continue its activities. Though, it was not easy for Field to kick start the company. By the end of October 2007, after four years, seven court hearings and court appeals, his company had lost around R400 million ($57.8 million) worth of investments. The company’s reputation was damaged, but Field and his team worked hard to win back trust and survive.