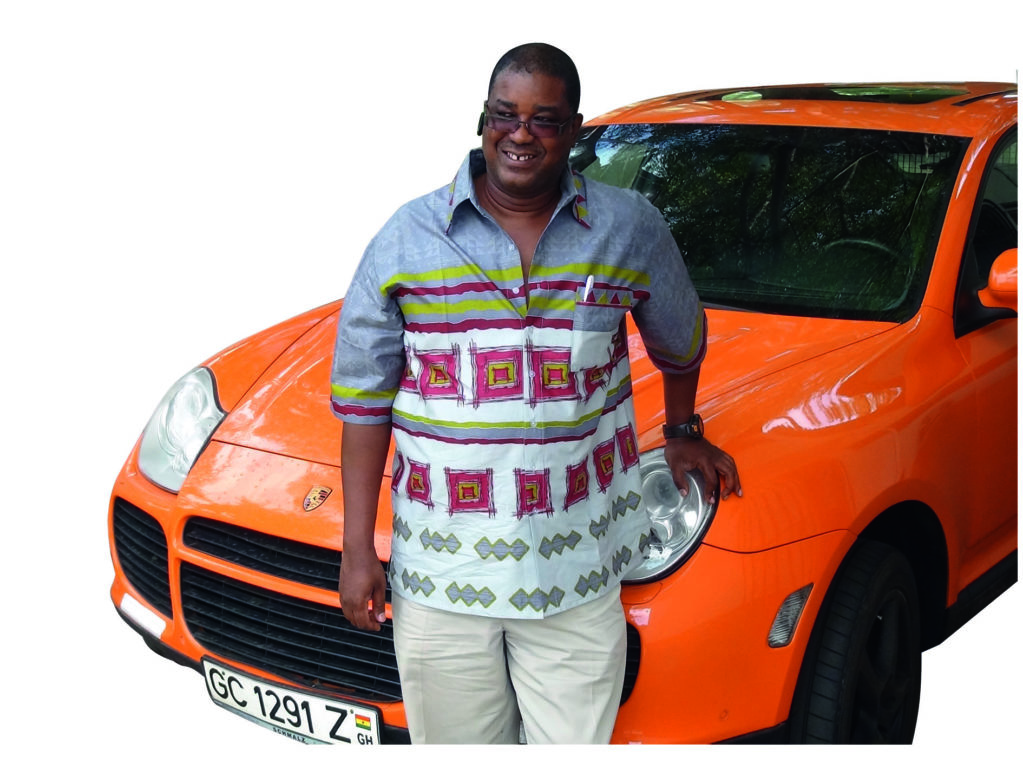

Herman Chinery-Hesse is piloting an orange Porsche sport utility vehicle around the hairpin bends leading up a mountain to his house in Aburi, in the misty hills just outside of Accra. “Put your seat belt on,” he warns, and screeches the tires.

These days, Chinery-Hesse’s racing hobby mirrors his life in the fast lane. He is the founder and CEO of SOFTtribe Limited, a company that provides business development software to African companies. On the Accra business scene, he’s known as the “Bill Gates of Ghana”—a title the 47-year-old shrugs off. The unabashed Pan-Africanist would likely prefer a Ghanaian nickname than one borrowed from an American software developer.

Herman Chinery-Hesse

“Africa is it,” he says. “It’s the next big wave. It’s waiting for development—every place else is so saturated, and people are finally spotting it. And they’re coming to us.”

Chinery-Hesse’s goal is to ensure Africa doesn’t miss the global information technology (IT) boat. His client base includes Nestlé and Unilever, and he has a regional development partnership with Seattle-based technology pioneer Microsoft. But despite the influx of global companies coming into Africa, he says there’s not yet a homegrown technology brand name synonymous with the continent and hopes that his company, SOFTtribe, working from offices in an understated two-level house near Accra Airport, could be the first. The company has just launched what it calls a “virtual mall”: an online hub where you can buy everything from a cinema ticket to a sweater from Angola.

“We want an African Google, an African Facebook. And it’s possible,” he says.

Despite Africa’s weak technology infrastructure, Ghana, at an estimated 20%, boasts the highest penetration in the region. He sees more potential in Africa than any other technology market in the world.

“Africa is where the richest need is,” he says. “If we get even 1% or 2% of African companies to buy our products, we [will be the next] Google.

“You should be able to access Africa from wherever you are in the world,” says Chinery-Hesse, mentioning his company as being “the gateway, the highway. I want something stable that makes people money.”

At SOFTtribe’s headquarters, there’s a decidedly mellow vibe—in his trademark khakis, rubber sandals and bright button-up, Chinery-Hesse maintains the casual style of Silicon Valley. Staffers mill on the balcony and walls are adorned with large canvas paintings of the beach.

On a recent day, the boss was in his favored work position—lying down on the sofa, four computers humming on the nearby desk. He dictated to his Hong Kong-educated Ethiopian assistant as she typed on a small pink laptop.

Chinery-Hesse paused to answer calls on his wireless mobile headpiece, a confusing move that causes his colleagues to joke: “Is he still talking to me?”

The space to sprawl is an achievement for Chinery-Hesse. When he first founded SOFTtribe in 1991, its programmers sat side-by-side in an outhouse—remodelled as a cramped office—behind his parents’ house in the same neighborhood.

“We were doing an international contract with Nestlé’s head office, and we would say ‘don’t come visit’ because they wouldn’t believe that this [cutting-edge software] was coming from the bush.”

A few years later, when the team had swelled to 28 people, Chinery-Hesse, unable to afford rent on the kind of space he needed, bought a freight container and piled in his operation. It housed the entire team and two air-conditioners for six years.

Today, from the comfort of its new home, the company is expanding at a clip that rivals one of the orange Porsche’s tight turns. By providing the internet bandwidth, hosting and software development capabilities to African companies—and the regional branches of multinationals—it has amassed more than 250 clients.

Chinery-Hesse is an unabashed Africa enthusiast who hopes to use technology and the internet to aid the wide spectrum of African business, from the Ford Foundation to a craftsman in Mali looking to sell his work overseas.

“We help clients with delivery, logistics; we make sure the merchandise is working. A lot of the time, we’re dealing with ordinary folks who may just have a mobile phone. We’re hand-holding,” he says. “My team is from everywhere—here, Ethiopia, Kenya. We see Ghana as a springboard to expand further into Africa.”

He speaks from experience—his home country provided the springboard for his own ambitions.

Born in Dublin, Herman’s mother is Dr Mary Chinery-Hesse, the former deputy director general of the International Labor Organization and the vice chairman of Ghana’s National Development Planning Commission. Her son was schooled in both Ghana and the United Kingdom and attended Texas Tech University, where, with the first computer boom underway, he discovered a talent for software coding.

Ever the pragmatist, he began his professional life as an engineer at a UK plasterboard manufacturer.

“If everything went wrong, I’d have a fallback,” he says.

The pay packet from the plasterboard manufacturer helped buy a computer costing 800 British pounds, and Chinery-Hesse began tinkering with it at home. At work, bosses took note of Chinery-Hesse’s interest in technology, and his American education, and moved him from mechanical to computer engineering.

Returning home for Christmas in the late 1980s, inspiration struck in an unlikely spot – an Accra nightclub, where friends were complaining that they didn’t have jobs.

“I made a 100 pound bet that I could find a job here by Monday morning,” he says. “Monday I woke up, jobless, and said ‘ouch.’ Then I remembered I had done programming in the UK, went onto the street, found a travel agent with a broken computer, fixed it, and…”—as word of mouth spread in a society that knew next to nothing about technology—“… I was inundated with offers.” A few years later, he founded SOFTtribe.

If the company’s original hurdle was to introduce software to a nation that didn’t know what it was, today its challenge is a bit more complex—figuring out how to incorporate traditional software with the growing influence of the internet.

In a sign he’s been successfully able to navigate Web 2.0, Chinery-Hesse was invited to speak at tech conference TEDGlobal in Tanzania in 2007, where he introduced SOFTtribe’s most advanced venture, Black Star Line (BSL), an e-commerce business which coordinates trade carried out via mobile phones and the internet, a model “combining transaction brokerage and a virtual marketplace”.

Funded by an angel investor, it’s a system of technology that’s a cross between eBay and PayPal, both of which are scarce in Africa, but are booming in the US, Europe and Asia.

“Africa can’t trade with the world, hence our poverty,” he says. But before it can open its gates to the world, the tech czar would like to see a businessman in his country transact with someone in Nigeria or the Congo or Malawi—without the usual red tape. “We can use technology to bypass borders and bureaucracy and unleash inter-Africa trade,” he says, “where someone in Kenya would be able to buy something from a man in Ghana.”

SOFTtribe is being recognized globally. The TED platform was a sign of acceptance from the international tech community, as were invitations to speak at the US’s top two business schools, Wharton and Harvard, and at Cambridge in the UK.

Chinery-Hesse’s profile in Ghana continues to rise; he is currently an Assessor at Ghana’s Commercial Court and his homes—and office balcony—are more popular among Ghana’s elite than nightclubs.

On a misty September night at his weekend home in Aburi, the deck was filled with the usual motley crew—business associates, locals, friends in from London. Everyone drank good wine. Mist swirled in the distance. Someone asked about road directions, inciting a spirited discussion. Chinery-Hesse, of course, was ready with the only answer that made sense—maps, after all, are for a world before technology.

“Use GPS,” he said, and the discussion was over.