TOPLINE

The World Health Organization announced Saturday the spread of monkeypox does not yet constitute a public health emergency, but WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said “serious concerns about the scale and speed of the current outbreak” remain.

KEY FACTS

A WHO panel made the determination at an emergency meeting called to determine if the escalating spread of monkeypox qualifies as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), which would push countries to take action to limit the virus’ spread.

The committee noted that most monkeypox cases during the recent uptick have been confined to communities of “gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men” who are not vaccinated against smallpox, but warned there is “a risk of further, sustained transmission into the wider population that should not be overlooked.”

The committee’s decision was not unanimous, but its members reached a consensus on their decision, according to the WHO, which listed several scenarios that would trigger another emergency meeting to reconsider.

An increase in the rate of case growth in the next 21 days, signs of “significant spread to and within additional countries” and an increase in the severity of cases are among the reasons the panel would reconvene.

CRUCIAL QUOTE

“This is clearly an evolving health threat that my colleagues and I in the WHO Secretariat are following extremely closely,” Tedros said in a statement.

KEY BACKGROUND

A PHEIC is the WHO’s highest level of alert possible under international law. It is intended to sound the alarm for countries to take immediate steps to stop an outbreak and to provide guidance on what measures they should be taking to achieve this. It’s also a signal for nations to activate their own emergency plans, such as boosting funding, vaccination or testing. Gian Luca Burci, a professor of international law and former WHO legal counsel, told Forbes a declaration can provide “convenient political cover” for national politicians to implement potentially unpopular policies. Under international law, nations are expected to take steps to address a PHEIC, though they are not compelled to act—many nations took weeks to respond after the WHO sounded the alarm on Covid-19 in January 2020. Clare Wenham, an associate professor of global health policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science, told Forbes there is scant empirical evidence on what actually happens if a PHEIC is declared, and said a declaration on monkeypox could mark a “test” for the WHO’s authority post-Covid.

TANGENT

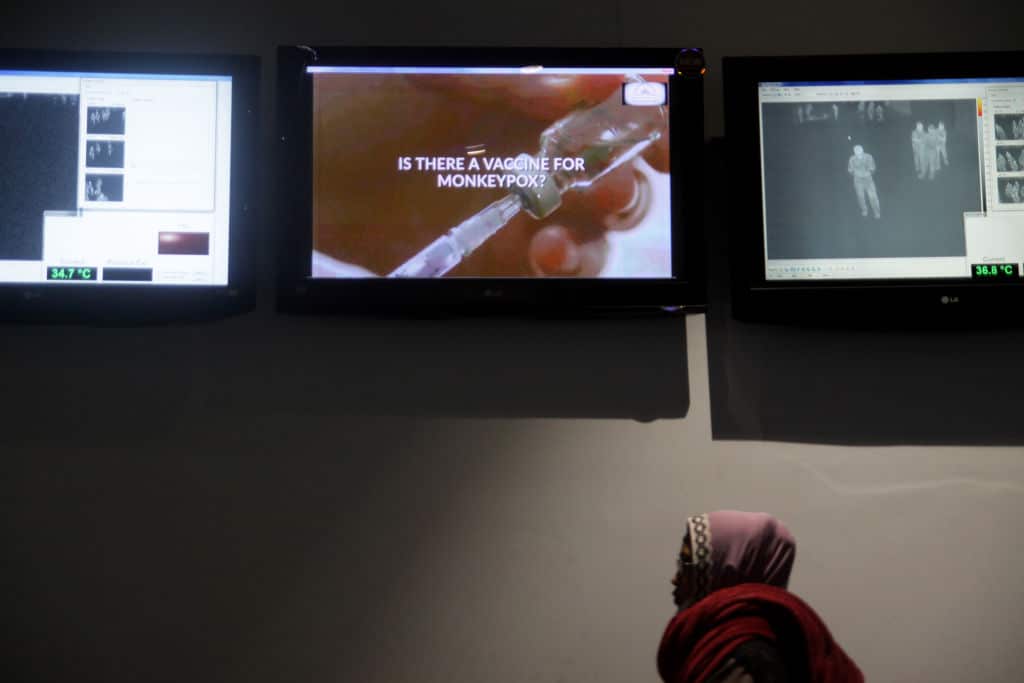

Monkeypox does not spread easily between people, and is primarily transmitted through close contact with an infected animal or person or objects like towels, clothes or bedding that have been contaminated by someone with an infection. Less commonly, the virus spreads through respiratory droplets produced when people breathe, cough, talk or sneeze and particulars of the recent outbreak has experts are exploring the possibility the virus could be transmitted sexually after it was detected in the semen of some patients. While the disease has spread in some parts of Africa—where animals are believed to harbor the virus—for decades, cases elsewhere have been rare and almost always (though not exclusively) linked to travel in the region. Treatments and vaccines against monkeypox are available, though they are in limited supply and data on their use is scarce.

WHAT WE DON’T KNOW

While the monkeypox virus is relatively well known, the near-simultaneous emergence in several areas where it is not normally known to spread alarmed experts earlier this year, and suggests the virus may have been quietly circulating for some time. “Person-to-person transmission is ongoing and is likely underestimated,” Tedros warned. There are many unknowns about how the virus has spread around the world and among whom it is spreading, something exacerbated by testing issues. In Nigeria, Tedros said the proportion of women affected by the disease is “much higher than elsewhere,” though it is not understood why. In newly affected countries—such as in Europe and North America—cases have predominantly been among men who identify as gay, bisexual or who have sex with men. This has prompted targeted health measures aimed at at-risk communities, as well as homophobic backlash, though experts warn stigma will make it harder to contain the disease and does not reflect the fact that the virus will infect anyone, regardless of sexuality.

BIG NUMBER

3,200. That’s how many cases of monkeypox have been confirmed and reported to the WHO from 48 countries in the six weeks since the organization was notified about three cases in the U.K. that were unrelated to travel, Tedros said at the start of the emergency committee meeting to discuss the outbreak on Thursday. One death has been reported in Nigeria. There have been an additional 1,500 suspected cases and around 70 deaths reported this year in Central Africa, Tedros said. Primarily, these have been in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but there have also been reports in the Central African Republic and Cameroon.

FURTHER READING

What To Know About How Monkeypox Spreads—And Whether You Should Wear A Mask (Forbes)