Forty-five years later and now among Africa’s 30 richest people with a net worth to match–he is worth more than $545-million–Raymond Ackerman still bears the scars from the worst day of his life. The day still gnaws at his mind, fresh, like it happened yesterday. It has driven and defined his life.

“It was a Monday morning in 1966,” Ackerman, now 80, recalls. “Norman Herber, the chairman, called me in and just said you are out.”

The least Ackerman thought he deserved was an explanation. Certainly, for someone who had served the company with distinction, for the previous 15 years–at least as far as he was concerned. He had joined the retail group, Greatermans, as a 20-year-old trainee, rising through the ranks to become MD of its struggling groceries division, Checkers. He had built the besieged subsidiary from three stores to 85 by the day of his firing.

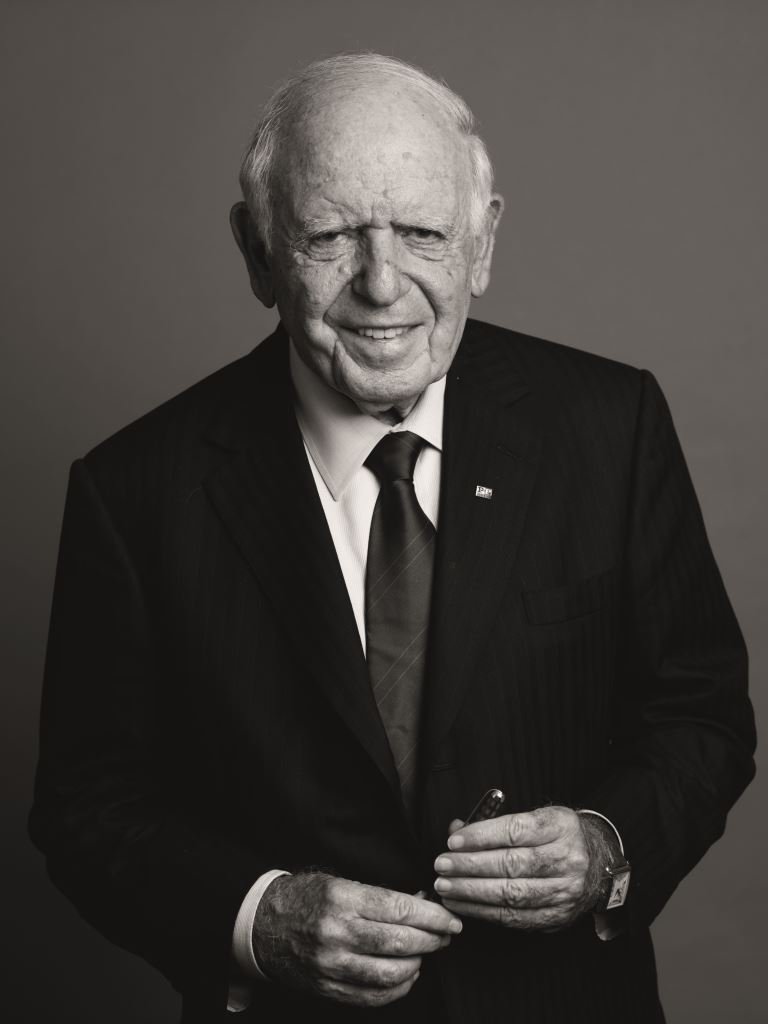

SOUTH AFRICA – Date unknown: Pick ‘n Pay Chairman, Raymond Ackerman (Photo by Gallo Images/Sunday Times)

To Ackerman’s shock and horror, Herber was in no mood to explain, nor did he seem to think he owed anybody anything, least of all his underling.

“I said Norman, what went wrong? He wouldn’t explain. He just said ‘Raymond, I know we are close. But from today, you are out.’”

With his last paycheck, off went Ackerman to his wife, Wendy, who was at the time heavily pregnant with their fourth and last child. Although equally devastated, she would give her husband the best advice he ever got.

“Raymond, this is the best chance of your life–open your own business.”

But where was the capital going to come from?

As Ackerman pondered the question, he remembered an American businessman he had met during the time he was learning the ropes at Checkers. He had told him: “Business is 90% guts and 10% capital.”

For the next few months Ackerman and an accountant friend would go around speaking to a wide range of potential investors trying to convince them to buy into their business idea. About 40 backers would line up and the following year, 1967, a new retail group, Pick ’n Pay, listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

Ackerman and company would start out by buying four small Cape Town stores, laying the foundations for what is today a US$6.76-billion turnover company.

Pick ’n Pay is now South Africa’s second largest food, general merchandise and clothing chain. The group boasts 775 stores, mainly in South Africa but also in neighboring countries: Botswana; Zimbabwe; Zambia; Mozambique; Namibia and Swaziland. The company is also in Mauritius. According to the latest annual report, 100 more stores are due to open over the next financial year. The company employs more than 38,000 people.

With that kind of achievement many men of Ackerman’s age would probably want to spend the rest of their lives in peace–traveling the world; looking after their grandchildren or simply tending the garden. The last thing you would expect from such an achiever is appetite for a new, if not hazardous, struggle.

Well, like an old war-horse sniffing gun-powder, Ackerman is bracing himself for a new war. In it, he wants to gallop ahead of younger stallions, including his eldest son Gareth, whom he anointed as his successor and chairman in 2010.

Ackerman discloses, during our interview, that he has drafted himself into a select and close-knit team that is working hard and spending a fortune on a battle plan to fend off marauding United States invader, the world’s biggest and ruthless retailer: Walmart.

Walmart–a multinational both feared and respected–bought a majority stake in Massmart, South Africa’s third largest retailer. It was an acquisition opposed by unions that went through a turbulent hearing at the Competition Commission in Pretoria. Many in the unions feared the company’s rough-and-ready approach to labor relations. Other South African retailers feared they’d be undercut and shoved out of the market by Walmart.

CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA ñ 28 May 2011: Businessman Raymond Ackerman receives an honorary doctorate from the University of South Africa (UNISA) in Cape Town, South Africa on 28 May 2011.

(Photo by Gallo Images/Foto24/Nasief Manie)

In the aftermath of regulatory approval, the US outfit made no secret of its intention to capture a much larger market share in South Africa by starting a price war with the likes of Pick ’n Pay.

“With Walmart coming, we want to be the best in every part of our business. We’ve redone our buying; we’ve redone our warehousing; and we’ve redone every aspect of our business. We are gearing ourselves for the fight, a very big fight.”

And fighting, it must be said, is something Ackerman is used to. After all he has spent a lifetime fighting his South African rivals OK and Checkers in the cut-throat world of supermarkets–where the cheapest baked beans can be a shot to the jugular.

I put to Ackerman that Walmart, with its deep pockets and huge operations around the world, could prove to be the toughest, if not most formidable, opponent he has ever faced.

“We’ve done our homework and will fight a good fight,” he says.

“I’ve studied deeply what they’ve been doing but I don’t want to get into that. I don’t think they’ve succeeded everywhere. We are looking at the weaknesses that we’ve picked up around the world, what countries they’ve done well in, what countries they’ve failed in. We are gearing ourselves to fight a good fight, not against a ruthless guy, but against a company that has shown that it’s got weaknesses.”

It also turns out that Ackerman’s much-publicized retirement, announced two years ago, never really was. Or, as he prefers to put it, he is “technically retired.”

Ackerman still goes to work everyday. He still arrives at 8am. In addition to attending to social responsibility programs, he advises the executive management team on administration and merchandising.

What happens when his son, Gareth, and his team don’t take his advice?

“I try not to interfere with the day-to-day running. They listen to some of my advice and sometimes they don’t. When they don’t take my advice I get upset but I don’t take offence. If I took offence, then they would feel that I’m interfering. It’s not easy, by the way. It’s not easy retiring when you’ve built a business from scratch.”

What some may call meddling or refusing to let go, Ackerman merely calls passion.

“I’m passionate about what I do. I want to build a company that will last forever”.

The only way to make a business last forever, Ackerman advises, is by sticking to good values–something he says he tells everyone who cares to listen to the story of his success, including the scores of entrepreneurs, business leaders and students he always gets invited to inspire and motivate.

It all goes back to advice a Professor gave Ackerman and his class back in 1949, at the University of Cape Town, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Commerce degree. The lecturer asked all those who wanted to go into business so that they could make money, to put their hands up. Almost everyone raised their hands, including Ackerman. The professor then advised the class: “If you think making money is the purpose of business, you are going to fail.”

Ackerman took the advice and it is his motto to this day. It is something he says analysts always miss, whenever they examine his business performance.

“Analysts are meant to analyze a company by this triple line and corporate governance–but analysts will never ask me about what I do on social responsibility, what I do for my people. They just want to see profit…profit…profit. I want to build a company that will last forever. The analysts just want profit growth, profit growth, profit growth.”

“South Africa, in my opinion, needs desperately more businesses involved with triple line reporting. You must give back to the community. The more you give, the more you will succeed.

By giving, Pick ’n Pay removed an albatross from around its neck.

When Nelson Mandela came into power after South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994, one of his first moves was to ask the country’s white business establishment to sell a stake to their black counterparts, in a program now known as Black Economic Empowerment.

Ackerman says he grabbed the opportunity with both hands, by creating franchises for black entrepreneurs. The result was a win-win solution that helped both black entrepreneurs and Pick ’n Pay grow. Ackerman converted some of his underperforming grocery stores into franchises and has been building scores of new stores in townships. Many of the franchise stores are owned by black entrepreneurs.

“It was a major shift for Pick ’n Pay, now half our stores are franchised. I thank Mr. Mandela for influencing me,” he says.

Ackerman’s relationship with politicians, though, has been strangely ambivalent–at best.

In the dangerous days of apartheid South Africa in the 1970s and 80, when the country was in flames; many well-off whites were emigrating.

“Sure, I had misgivings about our decision to stay. Thank God we decided to stay with it,” he says.

In those difficult days, Ackerman met politicians. He vividly remembers a talk with Prime Minister, B.J. Vorster, who was in power when black students took to the streets and were mowed down in Soweto in 1976. It was on Vorster’s watch that more opponents of the apartheid regime were detained in a climate of racial conflict.

“It was quite an amazing thing, we wanted to promote black managers but it was against the Group Areas Act, [the legislation that apportioned land by race]. I went to see him [Vorster] and said we are doing it. He said, ‘I know you are doing it, and it’s against the law’. I said, ‘here are letters from ministers’ wives saying how courteous this or that manager is’. I showed him these letters that my wife had prepared. He turned around–I won’t forget that day–and said, ‘Mr. Ackerman, go ahead, even if you are breaking the law I won’t arrest you’. I asked, ‘do I have your word ? Can I have it in writing?’ He said, ‘go ahead, I won’t arrest you’. I said, ‘give it to me in writing’ and he said, ‘I won’t but you must do it’.”

In 1980, Ackerman went to see Vorster’s successor, P.W. Botha, a very stubborn man–who was called ‘Die Groot Krokodil’”, Afrikaans for ‘the big crocodile’, who oversaw the most violent years of apartheid rule. Ackerman wanted to discuss several issues, including a housing scheme he was contemplating for his black managers: “I asked him why we can’t have houses for blacks? Why not have a 99-year lease like they have in Sweden and Finland. He called in one of his ministers. I think it was Connie Mulder. After about a week of discussions, Botha came up with a 99-year-lease-hold, which was later changed to full ownership.”

Ackerman would also meet F.W. de Klerk, who was a senior Cabinet minister at the time.

“There was such a breath of fresh air about him,” Ackerman says of the man who would go on to succeed Botha, and later, release Mandela from prison.

“I’m not trying to say we played an enormous role,” Ackerman adds quickly, “but we played a role.”

Even in the so-called “new South Africa”, where there’s “tons of things going wrong,” Ackerman says he will, in his small way, continue to play a very positive role. That’s not to say he’s happy with everything that’s going on in the country.

For example, he wouldn’t mind being taxed more–a call that has been made by such people as Nobel Peace Prize laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in part as a gesture towards reconciliation and redress. “I’d be happy to pay an extra tax to uplift and help entrepreneurs help businesses start,” Ackerman says, “but we’ve got to deal with corruption.”

He adds, however, that he always reminds people that corruption is not just in government, but also in the private sector, and that inequality and unemployment were “twenty times worse in the sixties and seventies.”

As a believer in entrepreneurship, in a free economy, he was delighted to hear South African President, Jacob Zuma, reject the calls for mine nationalization.

“You can’t create jobs through government. You need to excite the entrepreneur to invest capital and to invest in new things. I respect the fact that the government has by and large left a free economy.”

He is also delighted that government is not agreeing with the Congress of South African Trade Unions–the biggest workers union which is also an ally of the governing African National Congress–that labor brokers should be banned in South Africa.

“Unions hate labor brokers because when there’s a strike, the labor brokers come in and soften the strike and we can run the business without them. I hope he (President Zuma) doesn’t listen to labor unions. If he cuts out labor brokers he’s going to play into the hands of labor unions for strikes,” Says Ackerman.

So, when all’s said and done, what would this doyen of retailing and grandfather of 12 like to be remembered for?

“I’m not saying I’m different. I’m not saying I’m clever, I’ve just worked my whole life to rebuild myself after I was fired.”

The lesson for entrepreneurs?

“Find something you are passionate about, and make it your life’s work.”