The last time I saw Alf Kumalo, it was a fitting place to meet one of the true greats of journalism. He was working, a camera slung around his neck, as always, on one of the biggest stories on the planet that day. We were at Milpark Hospital in Johannesburg, in early 2011, where hundreds of journalists from around the world descended after Nelson Mandela had been admitted in poor health.

Kumalo, the man who had been photographing his friend, Mandela, for more than half a century, was his gentlemanly self. He stopped his car, smiled and shook my hand with a warm greeting. He didn’t quite look himself that day but as he drove off, I mused that the man epitomized everything I respected in journalism: hard work; professionalism; integrity; a sense of fun; guts and grit; in short, qualities of man lauded across Africa, for more than half a century, for capturing the history of the struggles of his continent.

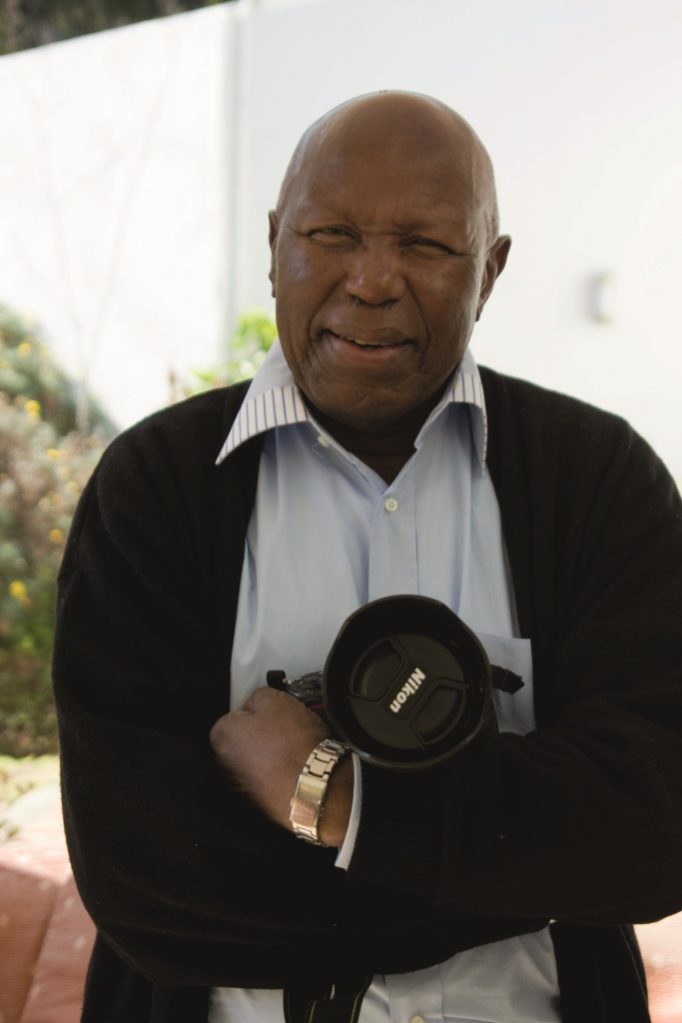

In this trade, riddled by braggarts and self-promoters, where even a spin doctor can command columns in newspapers—Kumalo was a man who wore his eminence lightly. He also wore the finest, smartest, clothes. Now, most photographers wear jeans and scruffy jackets; Kumalo dressed to the letter with a handkerchief nestled in the top pocket of a sharp jacket.

Kumalo appeared in the first edition of FORBES AFRICA in October 2011 when we interviewed him about his role, where he played himself, in the The Bang Bang Club, a film about the rough world of journalists covering South Africa’s political troubles.

“The Bang Bang started in the 1990s, but we’d been banging on for years,” laughed Kumalo.

It had been a long journey for Kumalo from his birth, more than 82 years ago, in Alexandra Township, just down the road from the FORBES AFRICA offices in Sandton. He went to college in Evaton, in the Vaal just outside Johannesburg. His eye for a picture saw him work for a number of publications, including South Africa’s Drum magazine and The Star, photographing every step on the road to freedom for millions of Africans. It was a fascinating journey that would see him befriend boxing giant Muhammad Ali—Kumalo was a successful amateur boxer himself—along with everyone from Moroka, Mbeki and Mandela.

I got to know Kumalo in 2009, when I interviewed him for the CNBC Africa documentary Liliesleaf—The Untold Story. It was a trilogy I produced on the underground movement in the 1960s, which hid out at Liliesleaf farm in Rivonia. Their capture, in a raid on the farm, led to the world-famous Rivonia trial, in which Mandela was sentenced to life.

Kumalo was at the raid and trial. He was lucky enough to have won a car in a photographic competition, so he was able to drive to cover the raid. In the car he packed a blue overall so he could disguise himself as a worker and avoid manhandling by the police. Here, he used his famous techniques to shoot, without anyone knowing, which included balancing a camera on his head and clowning around while the shutter clicked away. This hard work and guile brought Kumalo some of the most stunning pictures of his generation. He told me that he took a picture inside the court at Mandela’s Rivonia trial in Pretoria—an action that would have meant prison back in the day—and hid it away when his editor disapproved.

“I think I still have the negative somewhere, I will have to look it out,” he said to me, but took the secret of the missing Rivonia photograph to his grave.

As a fellow journalist, from the days before cut-and-paste hearsay, I always appreciated how much Kumalo had been an eyewitness to history; that he had felt, as well as recorded, the momentous stories of Africa. I shall never forget the pain in his face when he told me of how he saw police tossing casually the bodies of dead schoolchildren in piles during the Soweto uprising in 1976.

Kumalo suffered for his craft. He was beaten up and arrested more times than he could remember. Once the South African police cracked his skull with a rifle butt and then charged him with fighting police and resisting arrest. The case dragged on for nine months, before charges were dropped on condition that Kumalo stopped shooting pictures. It was like telling the Limpopo River not to flow.

“I shot pictures all the more; I was angry and defiant,” said Kumalo.

Through it all, Kumalo never lost his sense of fun and love for the job. I recall the twinkle in the eye, when he told of driving to Francistown, in Botswana, to cover the escape of two South African underground activists from Liliesleaf: Arthur Goldreich and Harold Wolpe. The two had broken out of police cells in Johannesburg and fled to Swaziland, hidden in a car boot, before flying to Botswana dressed as priests. Kumalo recalled the hectic night drive, with a journalist, along the dirt road to Francistown where they were more afraid of lions than speed traps. Kumalo risked the lions as he jumped out of the car to retrieve the game road kill for the pot, his colleague was afraid to follow.

“He was in the driver’s seat taking a pee through the door saying, ‘I am not taking the risk, I am not mad like you!’” chuckled Kumalo with a laugh that could light up a room.

It was a more somber occasion, laced with tears, at City Hall in Johannesburg when those who knew Kumalo gathered, on a warm October afternoon, to remember his life. Winnie Mandela was there, as was legendary photographer Peter Magubane, who stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Kumalo in shooting many of the stories of the day.

“Bra Alf never hurt anyone’s feelings. I never heard him make a derogatory comment about a colleague,” says poet activist, Don Mattera.

Veteran journalist Hopewell Radebe recalled how the gentle man, with a camera, always had time for rookie reporters.

“On a job, he used to call you aside and say, ‘This is how you behave and when things get tough you do this…’ Alf proved the lens of a camera can be as powerful as an AK-47 in freeing the people from the yoke of oppression,” he says.

There were tears from the many young photographers trained by the great man, who lamented how he struggled to raise money for his college in Soweto. Kumalo could have been forgiven for thinking that he was denied the monetary reward of an illustrious career. He complained to me that people often stole the images he had fought hard to capture.

All of the photographers in the room lent their cameras for the photographic equivalent of a 21-gun salute. As the shutters clicked away everyone paused for a moment to contemplate a world of journalism that is much poorer for the loss of Alf Kumalo; the kindly king of the lens.