It has a claim to being one of the most photographed houses in Africa. It was the first house in Africa to be featured in the prestigious US Architectural Digest in November 1996; it appeared on the cover of Marie Claire and hosted a photo shoot for the St. John Collection for Saks Fifth Avenue in New York.

The African Heritage House is the fruit of years of sweat and toil by Alan Donovan, who has dedicated his life to collecting, promoting and preserving art from Africa. The house resembles the mud mosques of Timbuktu and the Grand Mosque in Djenne, Mali, which he saw on his first journey across Africa in a VW bus in 1969. He came to Africa in 1967 as a food relief officer for the US State Department during the Nigerian-Biafra war. In the midst of war, death and suffering, Donovan fell in love with Africa’s art and culture.

O It has a claim to being one of the most photographed houses in Africa. It was the first house in Africa

Donovan is an art collector, designer and proprietor of the African Heritage House. Forty years ago, together with his wife, Sheila, and Kenya’s second vice president, Joseph Murumbi, they co-founded African Heritage—Africa’s first Pan African gallery in Nairobi, Kenya. According to a World Bank report, African Heritage became “the largest, most organized retail and wholesale operation of its kind in Africa”, and a major source of African art and crafts from Africa to the rest of the world. In its heyday, it had 51 outlets selling around the world.

Donovan is famous for staging Kenya’s African Heritage Festival, an extravaganza that went around the world showcasing Africa’s rich art and culture. Many of the models in the shows wore jewelry designed by Donovan, and went on to become stars in their own right. One of them was Iman, the most famous model to come out of Africa; there was also Khadija, who was fashion maestro Yves St. Laurent’s first star model from Africa.

Donovan has collected artefacts, masks, paintings, textiles, ornaments and sculptures for the last four-and-a-half decades.

A visit to Heritage House is strictly by appointment. Donovan gives a personal tour of the three-storey house, which takes at least one hour.

The African Heritage House in many ways is a story of Donovan’s life. The design of the house was inspired by the mosques in Timbuktu, Mali, Emir’s houses and palaces in Nigeria, and Ghana’s mud houses of Navrongo. The latter are round or rectangular mud houses painted in geometric designs of ochre, brown and ivory hues. These features can be seen in the exterior of the house. Before commencing construction, Donovan also visited the mud palaces of Morocco and learnt how builders make bricks with straw and mud. In the end, Donovan opted to build the house with stone blocks covered with dyed plaster.

In the house, Donovan has hoarded his African collection: ceremonial daggers from Nigeria; Turkana headdresses made of ancestral human hair; Bapende masquerade dolls from Zaire; Kente cloth worn by the Ashanti royalty; Kenya’s Kamba beadwork; necklaces from Egypt made of rare quartzite clay; beads worn by a Shango priest in Nigeria.

Among the fascinating items are Ibeji dolls made by the Yoruba women of West Africa who have a very high incidence of multiple births. The children of multiple births—called Ibeji—were thought to share one soul. If one of these children died at birth, the mother would carve a wooden effigy for the dead child. The mother would feed the doll like the living child. Ibeji dolls have become one of the most popular pieces of African art and can fetch up to $10,000.

Donovan also has a large collection by some of Africa’s great artists, including a six-foot wooden piece called Three in One by East African pioneer sculptor Francis Nnaggenda. Vice president Murumbi lauded Nnaggenda in his opening speech for African Heritage beseeching the then Mayor of Nairobi, Margaret Kenyatta, and the Nairobi City Council to buy Nnaggenda’s mammoth works on behalf of the people.

“I own five of this man’s works and I am the only African who ever bought a piece from him. Otherwise, Africans should not get upset if their artists and art leave Africa,” said Murumbi.

The words fell on deaf ears and Nnaggenda went into exile in Texas for decades before returning to be Chairman of Fine Arts at Makerere University in Kampala.

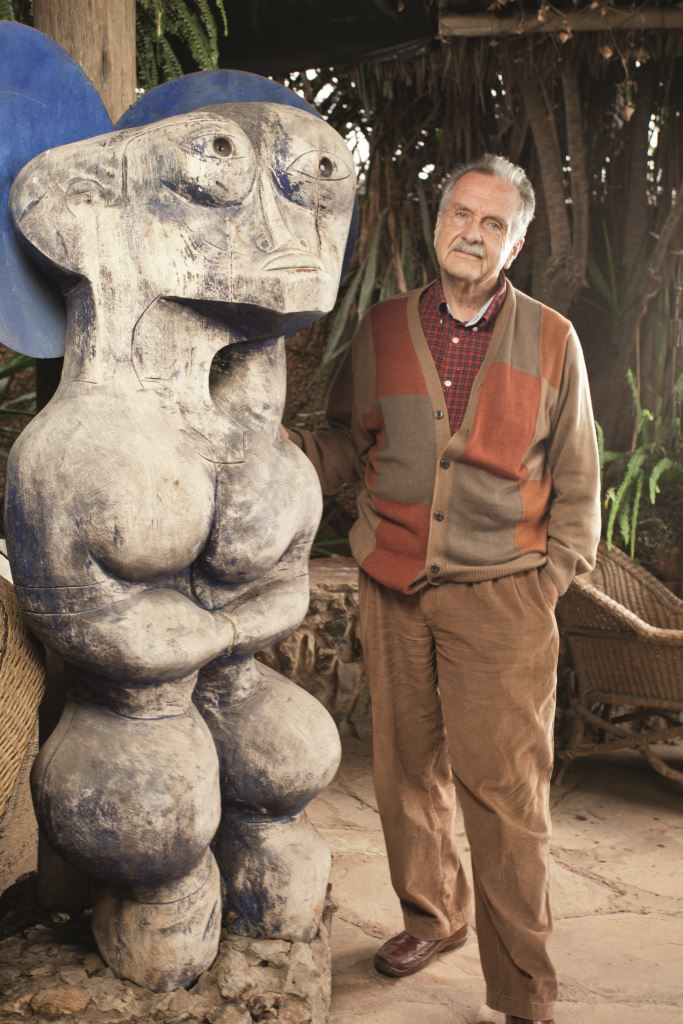

Alan Donovan with a traditional headdress, worn by a Karomojong warrior from Uganda

One of Nnaggenda’s towering metal sculptures, called “Woman at the Gate”, stands sentry at the Murumbi grave in Nairobi City Park. Thieves in search of scrap metal for the burgeoning scrap metal trade tried to dislodge the mammoth sculpture from its stone plinth, not knowing that the sculpture could fetch several million shillings if it were kept intact rather than a few thousand shillings as scrap metal. Nnaggenda sculptures are very rare now because the artist is quite old and there are only a limited number available. Thus, his pieces will always increase in value. Some of his works sell for over $50,000.

Donovan also owns a magnificent collection of Tinga Tinga art by disciples of the late Edward Saidi, a Makonde artist. The original paintings by Saidi can sell for up to $20,000 or $30,000, and are especially sought after by Japanese collectors. There is also a painting by a Haitian artist who “liked to paint animals”, says Donovan.

Inside the House, Donovan has pottery by Magdalene Odundo, who is based in London. “Odundo is Kenya’s most famous artist abroad but little known in Kenya,” he explains. She takes at least one month to make a pot. They are so few they can fetch over $50,000 each.

Then there is an amazing painting by Twin Seven Seven, a West African artist, who was one of seven sets of twins born to his mother; all the babies, but him, died at birth. Seven Seven died two months ago; he was a phenomenal artist, musician and dancer. His works only recently started to attract international attention at galleries in Europe and the US. Since his death, prices of his works are among the top tier for contemporary African artists who break $100,000. His former wife, Nike Seven Seven—who has had seven exhibitions at Nairobi’s African Heritage—also sells works for around $40,000. Other works in the house are paintings by Charles Sekano, a jazz musician and artist from South Africa who lived in Nairobi, and Ancet Soi, a pioneer artist from Kenya, who won a calendar award in the 1960s. His works are highly sought after and may sell for several thousand US dollars, along with the flamboyant works of Jak Katarikawe, a well-known Ugandan artist living in Nairobi.

For a long time, artefacts, masks, jewelry and textiles from Africa have not been accepted as art, but Donovan has helped to change all that. He says a sturdy prejudice exists from the West when it comes to African objects which is not there when discussing objects from other parts of the world. In his book, My Journey through African Heritage, Donovan writes: “If the object has not been seen in a museum or a book on African art, then it is not ‘African’, regardless of who created it. Besides, if the object is not something to hang on the wall or adorn one’s table, it cannot be ‘art’.”

After living amongst the Turkana in northern Kenya, Donovan wanted to exhibit their items as “art”, but when he tried to exhibit his collection in American galleries in 1970—after successful showings in Nairobi—he was told that they were “artefacts”, “utensils” or “functional” items.

“The Turkana do not need paintings on their walls or their donkeys. Their instincts and talents in producing their phenomenal designs is clearly art. Period. Why would I want to pay three million US dollars for a painting of a Campbell’s soup can, a ‘functional’ item reproduced by American artist Andy Warhol? This artefact may have been characteristic or pivotal in a period of Western consumerism, but is it art?” asks Donovan.

Is there money in collecting and selling African art? I ask. After a few seconds of silence, Donovan says yes, but adds a disclaimer about the types of art on demand.

“The value of many art pieces is based on their originality and age, and some of the things being sold now are not original,” he says.

The business of art is a thriving business in Africa. For example, an African Grebo female mask from Liberia costs $149; a framed Kuba cloth from Congo sells for anywhere from $100 to $1,500; a Bamileke Stool from Cameroon is worth $1,500; and a storage chest from Zanzibar can sell from $4,000 or more, depending on age, beauty, size and condition.

Donovan reiterates that art is indeed a viable business in Africa.

“Investment is not as important as the expertise. It is the affinity for the cultures and materials. Investment depends on the intended outlets; for instance, a huge chain of department stores or one exclusive gallery,” he says.

What will become of Donovan’s outstanding collection of art, crafts, textiles and artefacts in a house based on the vanishing mud architecture of Africa? Donovan seems puzzled. He discloses to me that he is in negotiations with several foundations and organizations and is also speaking to other private investors about plans to add suites and a hotel based on African traditional architecture.

What lessons has Donovan learnt as an art collector? “Sadly, many items in my house have disappeared and others will soon follow. As local demand for traditional items dries up, artists and craftspeople are forced to seek out new markets. Africans have embraced new religions and modern ways, their traditions have changed, some have vanished and we may lose in less than half a century what took ancient cultures millennia to create,” he explains.

“If you are interested in your heritage, you should collect it and cherish it as much of it is being lost as we speak, and in some cases even before we knew it existed.”

As for the house, he hopes it will remain intact as a museum for future generations.