A few months ago, he was a lone voice in the wilderness, now he is an international figure. Days after his acquittal in court, he has a campaign manager and his personal assistant tells me that for now he is not taking any calls. I speak to him in Johannesburg days later.

“I have not spoken to my parents yet due to security concerns for them. But, I know they have been praying for me. My wife was there throughout the whole court proceedings from morning to evening, fully pregnant. She is an amazing woman, I tell you,” he tells me from Johannesburg, in a visit that might last longer than his supporters want.

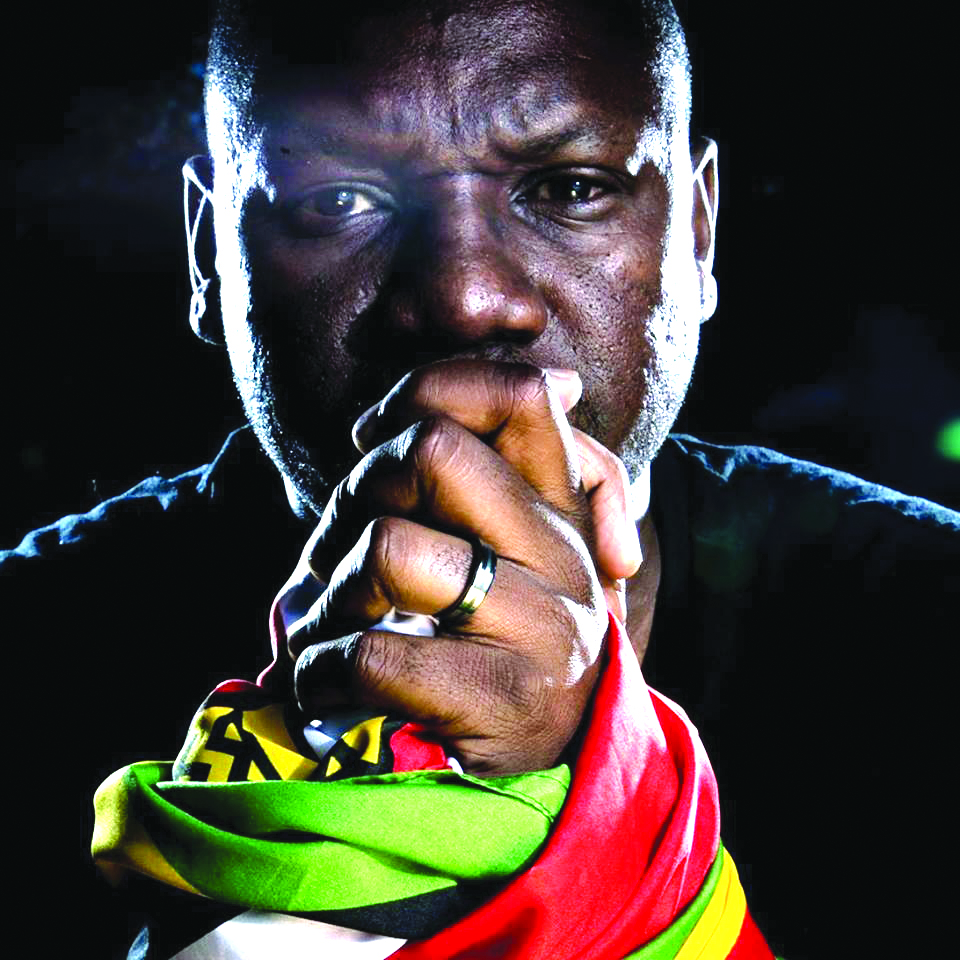

Evan Mawarire shot to international recognition on July 12, the day he presented himself to the police with a bible in hand and his flag around his neck. The country’s police had summoned him over a missing police helmet, a baton and suspicion of possessing subversive material.

“As we entered the cold, dark and smelly cell popularly known as ‘Baghdad’, I couldn’t help notice the brotherliness amongst the group inmates. They laughed, hit high fives and exchanged stories on what had landed them in for the first time or yet again. Nearly all the young men in the cell with me that night told me truth of their offenses. The one guy said to me ‘I deserve this and my desire is to stop stealing but I can’t boss, I don’t have a job’. Later that evening we shared some of my food that had been brought to me and he took it upon himself to ask anyone in the cell who had more than two blankets to give me one. I’ll be honest I’ve made a lot of friends in my lifetime, but that day in that cell I made some truly special friends. I met some real genuine Zimbabwean men,” says Mawarire.

The man of the cloth, who now had a blanket, was to also face charges of trying to topple his government. It all ended in acquittal and cheers at the Rotten Row magistrate’s court in Harare.

He is not the first to face such charges: Morgan Tsvangirai, Dumiso Dabengwa, Lookout Masuku and Ndabaningi Sithole, all opposition politicians, have been similarly accused down the years.

Mawarire’s crime: filming himself, using his mobile phone, complaining about his country’s malaise. The government’s only evidence, as they dragged him to court, was his posts on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. This is the story of Mawarire and his hashtag campaign #ThisFlag. In Zimbabwe, it’s risky to say the least.

Mawarire rallies hundreds of thousands of demonstrating ex-patriate Zimbabweans from Harare to London, Washington, Johannesburg and Melbourne. His words appear powerful enough to persuade citizens to shut down the country; on July 6, this turned Bulawayo and Harare into ghost towns.

On Sundays, he preaches to a congregation of 70, outside church, his sermons about politics, economy and corruption reach tens of thousands over the internet. His campaign is so powerful that the government is contemplating banning social media.

“This campaign is unique as it’s not led by politicians; it’s a campaign by ordinary citizens. We are calling for citizens to act now and act urgently, we are not going to be silenced and intimidated by the government. The call is for our government to account for and address corruption, injustice and poverty,” he says.

Mawarire, married with two children, grew up in Mazowe, 40 kilometers north of Harare, in a family of six. He studied at one of the country’s top schools, Prince Edward in Harare, before his father brought him back to the village. At 16, he was chosen as Zimbabwe’s first child president from the country’s schools.

Twenty three years later, Mawarire’s country is mired in poverty while the elite earn vast salaries; he claims billions have been lost to corruption. His campaign emerged out of frustration over scraping together school fees.

“We are completely unhappy with the situation, we have graduates who are vendors, our pensioners struggle to get their $80 out of their banks, and our best hospital goes for days without water that patients are now being asked to bring their own water,” he says.

Speaking out carries a heavy price.

“I’m definitely worried of re-arrest and I know they are trying to take me. I see danger and I fear for my life but I am more afraid of failing to explain to my children for having done nothing. Recently somebody called me and threatened to strangle me with the flag. Two government ministers have attacked me personally on social media. They are not used to citizens rising up and speaking to them.”

Jonathan Moyo, an opponent and minister in President Robert Mugabe’s cabinet, tweeted that US ambassador, Harry K. Thomas Jr, launched #ThisFlag at his residency. Mawarire and the US embassy deny this.

“The gap between real politics and cyber politics in Zimbabwe is so huge that one does not influence the other. Local politics remains the paradigm,” tweeted Moyo.

After Mawarire shut down the country Moyo had more to say.

“The notion that anyone can build Zimbabwe by shutting it down is an oxymoron,” Moyo tweeted.

“Moyo is trying to discredit the campaign by likening it to the Arab Spring. In all of my posts I made a call against violence; I know our government is well equipped to dealing with such kinds of resistance. They have accused us of being funded by the Americans, which is laughable and an indication of desperation,” says Mawarire.

#ThisFlag has shades of Baba Jukwa, the anonymous social media dissident that gave Mugabe and Zanu-PF headaches, so much so that a $300,000-reward was put on his or her head.

“I am not hiding like Baba Jukwa, I am not outside the country, people know where I live, and they know my salary.”

Editor of the Zimbabwe Independent and Chief Content Officer of Alpha Media Holdings, Dumisani Muleya, says Mawarire has rattled Mugabe’s government.

“It’s a defiance or anti-Mugabe regime campaign to rally people to fight the damaging leadership and policy failures of this government which have reduced Zimbabwe to ruins, hence panic by Zanu-PF ideologues to launch a counter. The regime is very afraid, anything can spark off an Arab Spring-like spontaneous uprising due to the explosive conditions on the ground,” says Muleya.

Bruce Mutsvairo, a social media researcher based at Northumbria University in Newcastle, England, says Africa has seen many campaigns of this nature.

“The problem is, in spite of their good intentions, most of these campaigns fall victim to clicktivism, that is to say, many people think by clicking a page, signing an online petition or producing a video on YouTube, they will achieve political change. Mawarire is encouraging a new generation of activists and citizens to speak up and that’s a good thing. But then you need someone to listen, otherwise it’s like fighting a losing battle.”

Mawarire’s campaign has seen him engaging officials, such as reserve bank governor, John Mangudya, in a bid to stop the introduction of bond notes, the first step to giving Zimbabwe back its currency. Mutsvairo believes more of that is needed if the clergyman’s campaign is to be successful.

“The real challenge is to transform remarkable online initiatives such his into offline political engagements,” he says. “No one had expected the reserve bank governor to listen to Mawarire and crew so that was quite an achievement but will he listen to Mawarire at all? Also, is anyone in Zanu-PF willing to engage Mawarire? Zanu-PF officials know the majority of people commenting online do not vote. They focus on the rural folk, most of whom have no idea who Mawarire is.”

That won’t stop Mawarire who wants to continue saying it loud and proud even if he risks going back to Bagdhad.