From Schoolboy To Rebel In A Month

Oupa Moloto is a little heavier and a lot wiser than 40 years ago when he ran riot in the streets of Soweto as a slender 19-year-old.

It was a day Oupa Moloto never thought would end in fire and tears. The children had prepared a peaceful protest; they were excited, as well as angry. Moloto was one of the thousands of unhappy students who didn’t want to be taught in Afrikaans, a language they felt was oppressive and merely the gateway to menial jobs.

Moloto was at Morris Isaacson High School, in Jabavu, Soweto. He was part of the South African Students’ Movement (SASM), which followed black consciousness – the philosophy that inspired young people to take pride in their race.

Through it, Moloto took the first step on a path that would see him locked up in 16 prisons and end up as a guerrilla fighter in Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the military wing of the African National Congress (ANC).

On a winter morning, he met up with his schoolmates to plan the march. Members of SASM were pushing for tougher forms of protest, but the masses held sway. A peaceful march it was; they had never marched in their lives.

“It was going to be exciting,” laughs Moloto.

On Tuesday, June 15, 1976, SASM members spread the word around schools. That night they painted placards against the system and Afrikaans.

“On the day of the event, June 16, school started a little earlier, the mood was different, the students were excited but the teachers couldn’t pick it up,” he recalls.

Few teachers knew of the march. At Morris Isaacson, slim, light-skinned and bearded Tsietsi Mashinini, the SASM leader, spoke passionately for the march at the morning assembly. They prayed and marched singing: “Senzeni na? Senzeni na?” (What have we done? What have we done?).

Other schools had heard about the march and headed to Orlando West to meet up with the main body. Hector Pieterson was not meant to be part of the march, he saw his sister Antoinette and ran to join her. He was shot and bled to death; his image went around the world and epitomized the brutality of the day on which scores of schoolchildren died.

The police blocked the streets and released a snarling dog sending students running in panic. The girls screamed and the boys stoned the dog.

“I don’t know where the petrol came from, but it was poured on the dog to burn,” says Moloto.

With angry youths fighting and retreating, the students scattered; attacking government property and anything to do with the system. By this time, parents had joined in, says Moloto.

Amid the chaos, there were workers digging a trench for a cable, under the guard of a white boss with hands in pockets. When the angry teenage mob came, the man was thrown into the trench and made to dig, says Moloto. The terrified workers were made to stand and watch their white boss dig with their hands in their pockets.

The violence swept through Soweto and spread to the train stations, forcing drivers to avoid stopping. Soon there were no longer trains, says Moloto.

“In fact, I think hijackings started in 1976, if you come with a company car, you will be taken out the car and they will drive around and burn it.”

As the uprising raged, bystanders suffered. There was a welfare office, not far from Morris Isaacson High School, run by Dr Melville Edelstein, who was loved by the people.

“When we were marching, he was standing at the gate wearing a white dustcoat and was waving to students, they had a good relationship, but in the evening he was brutally killed because of the color of his skin. He was white,” says Moloto.

A white teacher at Morris Isaacson was luckier and airlifted to safety by police.

Moloto woke up the next day and walked to school. He saw petrol tanks burning; the looting was chaotic.

Then came the crackdown. Police arrested students and many went on the run.

“When we went back to school days after the violence, we were told most of the leadership was arrested,” he says.

The shattered schools of Soweto came together again for a peaceful protest in the heart of the economy, downtown Johannesburg, on August 2. It was the biggest protest by far, says Moloto, but no one was hurt.

“The demand was to release those that have been arrested,” he says.

The students changed strategy.

“We called for a national stay away, that we should be indoors, nobody will be shot,” says Moloto.

The students decided to hit back at the economy by stopping people from going to work. They blocked and burned buses. In a few short weeks, Moloto evolved from a high school child, in blazer and tie, to a rebel.

Today, Moloto owns taxis, and has shares in the Rea Vaya Bus Rapid Transit System. He runs a butchery in Soweto and is also the project coordinator of the June 16 Foundation. After all, it was a day that changed his life.

Young rioters surround a burning bus during the Soweto Uprising in Johannesburg, 17th June 1976. The riots were a reaction against the government’s repressive apartheid policies. (Photo by Popperfoto/Getty Images)

“Light Show Me The Way, It’s Dark And The Road Is Far And Long”

Barney Mokgatle not only lost his innocence;

he also lost his country.

It was the very first shot that killed Hastings Ndlovu. That was when the wall of apartheid was cracked and it fell. If it wasn’t for that bullet, we wouldn’t have fought,” says Barney Mokgatle who was next to Ndlovu when he fell.

“Nobody can claim that Hector Pieterson was shot first.”

Mokgatle was the lieutenant to Tsietsi Mashinini who led the march in 1976. Mokgatle, looking younger than his peers, is now a senior member at church; he believes black consciousness is next to Godliness. He is also a member of the royal family at the Royal Bafokeng, near Rustenburg, in the North West province of South Africa.

Back in 1976 he was just another rebel in school uniform. When Ndlovu was killed, Mokgatle suggested the march be dispersed. Instead police descended on schools across Soweto looking for Mashinini; meanwhile Mokgatle was driving the wanted man around.

“Now the police were hunting us, we could not sleep in one place for two nights because there were people who were selling us out,” says Mokgatle.

Soweto activists Winnie Mandela, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, parents and principals pressurized Mashinini, Mokgatle and friend Selby Semela to leave the country. They argued that police wanted to kill them, rather than charge them, because in court they could attract public sympathy, he says. There was also a reward of R500 on their heads – a fortune in those days, enough to buy a new house.

When they tried to leave, there were roadblocks everywhere on the way to Botswana, Mozambique and Swaziland. Mashinini and Mokgatle organized a second mass demonstration across the country that they believed could prove a diversion. The ruse worked.

“When they relaxed on the roads and borders, that’s when we slipped out. We went through the bushes at night and there was a song we sang on the way,” he recalls.

As Mokgatle sings, I could feel the emotion and see the anguish in his face 40 years on.

“Sedi laka, mponesetse tsela

Ke tsamaye

Ho lefifi, hape ho sebaka

Ntsamaise…”

In English: “Light show me the way,

It’s dark and the road is far and long,

But when I’m with you I’ve got power…”

When they slipped out of South Africa, they did not know the way to Botswana. Those who had organized their escape moved the rebellious youths from one village to another.

“It was a relay in that fashion, at night, through the bush,” he says. “We could hear the lions and elephants from a distance and we were not aware of the danger, we had no fear.”

They reached the Botswana border the following morning; as they stood on the border fence, about to jump, Mokgatle remembers saying “We shall return.”

In the capital, Gaborone, journalists awaited them.

“That’s how South African police knew that we had skipped the country because of what they had read in the media,” he says. There were attempts to kidnap them and bring them back to South Africa. They knew they couldn’t afford to stick around.

Through Tutu and the World Council of Churches, they organized tickets to fly to Holland. When they landed in Lusaka, Zambia, they did not have a visa for an overnight stay, so they switched to British Caledonian to fly straight on to Holland even though they had no travel documents when they landed in London en route.

“Because we didn’t have passports, that’s where the problems started, that’s where we had to change destination, we were arrested and detained at Gatwick airport,” he says.

Journalist Jon Blair, a South African living in England, helped by telling media houses that three Soweto uprising survivors were detained at Gatwick airport. Years later, Blair made the first British documentary about the 1976 uprising.

“The following morning it was like bees coming to the airport,” he says.

The African National Congress (ANC), the Anti-Apartheid Movement and the Pan African Congress (PAC) were all there. The ANC took them under their wing because they were the most powerful. The trio refused to join the party because they had different political ideas. The ANC walked away, says Mokgatle.

“We had to fend for ourselves and that’s when the Nigerian embassy in Botswana contacted us. We went to meet Nigerian head of state Olusegun Obasanjo,” he says.

The military ruler told them Nigeria would support them if they were a national body rather than regional. Hence they changed from the Soweto Student Representative Council to the South African Youth Revolutionary Council (SAYRCO). From there, they were independent of the ANC, with Nigerian backing.

The Soweto schoolboys Mashinini, Mokgatle and Semela were sent to different countries. Mashinini to Nigeria; Mokgatle stayed in England; Semela to the United States.

Mokgatle’s role was to talk about divestment in South Africa, trying to tell the world why they were fighting the oppressive system, as well as raising funds for scholarships for those who didn’t want military training.

“We were conscientizing the world,” he says.

Mashinini and Semela did the same in their allocated countries.

“Our struggle helped the country, it made the ANC and PAC wake up, they had to fight rigorously. To be honest, the ANC and PAC were not active before June 16, it’s only when we fought and struggled and became independent in London that they realized that these guys are going to take the limelight from them, they had to wake up and do something,” he says.

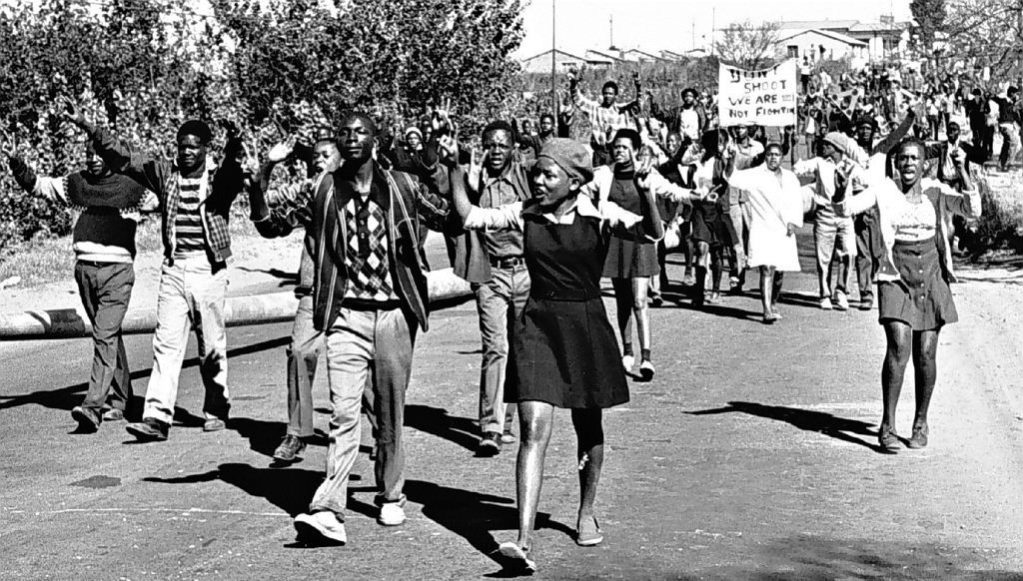

Demonstrators in the streets during the Soweto uprising, South Africa, 21st June 1976. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Mashinini died in Guinea where he was treated like a son by former president Ahmed Sékou Touré. He was introduced by Miriam Makeba – a South African singer and human rights campaigner nicknamed Mama Africa. Mokgatle suggests Mashinini was murdered.

“I still say to the comrades that there needs to be an investigation done, because what killed Tsietsi, nobody would say. Except for the gashing wounds behind the head, next to the eyes, we could tell he was beaten, who killed Tsietsi and who bought those people. He did not die a natural death,” he says.

Makeba, who was in Brussels, broke the news to Mokgatle in England.

“Miriam called me and said Barney your brother is dead, he passed on last night,” he recalls.

He asked her for a ticket to Guinea so they can arrange to take Mashinini back to South Africa. She refused and told him to go to Zimbabwe to meet the body.

He met the body in Zimbabwe in early 1990, by this time Nelson Mandela was released and exiles could go home.

Mokgatle came home in 1992; Semela still lives in the United States.